Artist Joel Coplin has spent the higher a part of three years portray what he sees by way of the window of his studio:

A girl showering with a hose beside barbed wire; a physique mendacity nonetheless at an intersection below a streetlight.

A sampling of Coplin’s paintings.

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Instances)

Then there’s an unfinished piece he calls “The Land of Nod,” an homage to the women and men who appear to defy gravity as they arrive down from the consequences of opioids.

It’s a part of a sophisticated relationship Coplin has with Phoenix’s homeless inhabitants, a mixture of compassion and frustration.

He and his spouse, fellow artist Jo-Ann Lowney, keep a gallery in an space often known as the Zone, about 15 sq. blocks on the sting of downtown that has been the fulcrum of town’s clashes over homeless coverage. They stay above the gallery, making up about half of the housed inhabitants within the space.

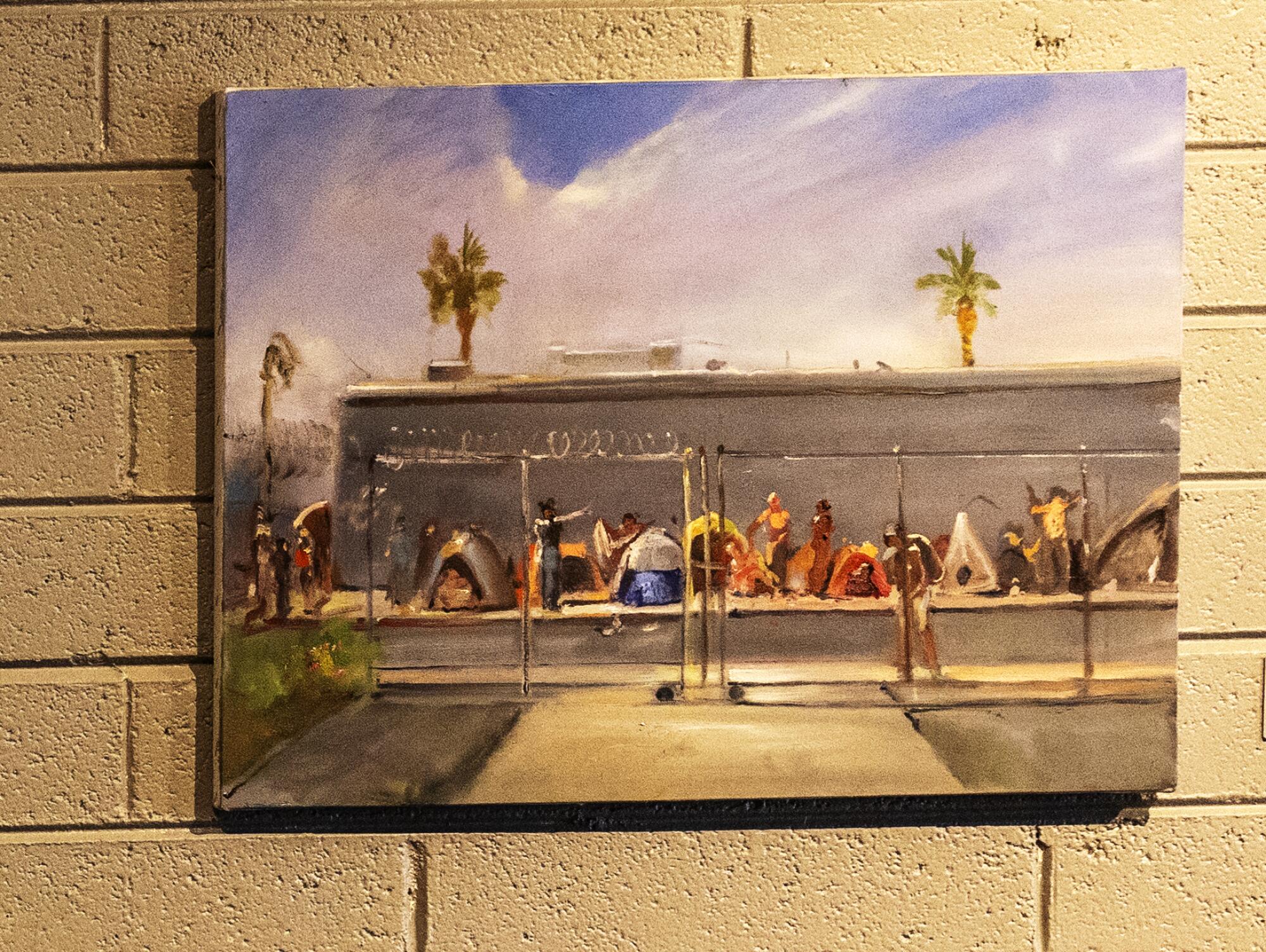

A Coplin portray depicting a homeless encampment.

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Instances)

Coplin, 69, has helped homeless individuals with meals, cash and medical payments. He has paid them $20 to take a seat for portraits, to inform their tales and to take heed to his.

However he additionally has had his face punched and glasses damaged when he went to search out one in all his homeless mates. And he has been a plaintiff in a lawsuit that has compelled town to clear the encampments that have been as soon as so prevalent he couldn’t open his downstairs gallery for 2 years.

Although the encampments have been faraway from Coplin’s neighborhood, the homeless nonetheless are available in droves to get companies on the Key to Change campus a block away.

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Instances)

“It simply ballooned into this unbelievable, like, barter city,” he mentioned. “They constructed edifices out of the tents that have been like three deep, and 50-gallon drums at night time with flames popping out of it — , cooking and music and singing and dancing. It was similar to an unbelievable road truthful — 24/7.”

Coplin moved to this property six years in the past after promoting his outdated artwork studio, east of town. It was low cost and he favored the neighborhood’s edginess. He had spent a decade in New York’s Hell’s Kitchen and received used to “stepping over individuals and junkies and all that.”

Folks slept on the road beside the gallery when he moved in, however that they had no tents and would go away throughout the day, he mentioned. He helped his neighbors purchase issues and allow them to use his lavatory, “kind of like a bit neighborhood.”

However after the federal appeals court docket choice restricted the police’s capacity to clear encampments, individuals began handing out tents, he mentioned. In the course of the pandemic, they left once more for a few yr after which got here again.

“So it’s been like coming and going,” he mentioned.

Coplin’s “Debbie on the Road along with her Stuff.”

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Instances)

His artwork studio and gallery, Gallery 119, is down the road from the Key Campus, a 13-acre advanced that features many of the metropolis’s homeless shelters and companies. It’s in any other case a comparatively barren space, except for his studio, some warehouses, a couple of outdated homes, a sandwich store, a cemetery and practice tracks.

Coplin and different property house owners sued town and received a court docket order to clear the a whole lot of individuals within the Zone in November. Homeless individuals nonetheless roam the world, however there are now not clusters of tents.

Circumstances are higher, however the metropolis nonetheless has the flawed resolution for homelessness, he mentioned: There ought to be smaller, extra specialised shelters all through town, moderately than a single super-campus of 5 blocks.

Amy Schwabenlender, the chief government officer of Keys to Change, the group overseeing the campus, mentioned clearing the world has introduced extra individuals contained in the campus, particularly throughout the day. At night time is one other story.

“However we nonetheless can’t shelter everybody so we all know X variety of individuals go away each night time and so they’re sleeping someplace,” Schwabenlender mentioned. “Not essentially secure, not meant for human habitation.”

As a Beethoven symphony performed within the background in Coplin’s studio, it’s onerous to think about the devastation outdoors that evokes his work. He remembers the night time he seemed out his window to see what he thought was an object “proper in the course of eleventh Avenue and Madison.”

Coplin in his dwelling studio.

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Instances)

Then he noticed motion — “an individual!” Automobiles weaved round however didn’t cease. He ran down to assist. However earlier than he received there, another person got here, and a mere contact startled the particular person.

“Up she jumped and began operating,” he mentioned. “I mentioned, ‘Oh, my God, that’s Elizabeth.’ I knew her.”

Coplin’s portraits have a quiet dignity — a person in a three-piece swimsuit; a girl trying up whereas she holds her canine, a blanket their solely safety from the rain.

Coplin’s portraits have a quiet dignity, together with “Soaked,” above.

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Instances)

He additionally seems to be to the previous for inspiration. In a single group scene, eight individuals are bent to resemble characters in Diego Velazquez’s seventeenth century work often known as “Los Borrachos,” or “The Drunks.”

He pointed to a historic library down the road that now sits vacant. He’s campaigning to make it a museum for the state’s artists. He retains hope that the world can develop into a spot the place individuals will come to purchase his artwork and respect the potential he sees.

“That is the ultimate frontier,” he mentioned. “All different features of the downtown have been taken up.”

He has all the time rejected the thought of gentrification, “however now I’m on the opposite finish, and I would like the gentrification. And I would like condos.”

Lately, somebody known as to supply him $940,000 for his property, he mentioned. He advised them no.