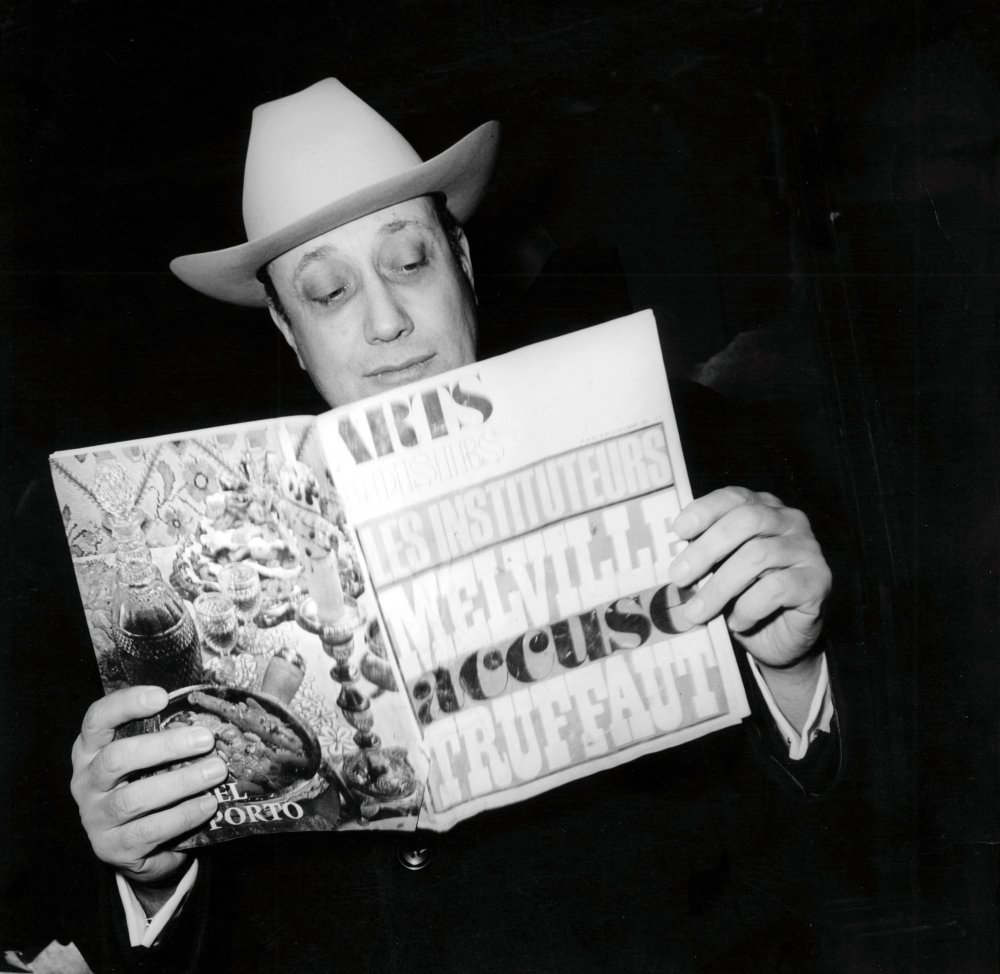

Jean-Pierre Melville, 50 years old, ten films since 1947, is the only director in the world to possess his own studios (they have burned down, but no matter, they can be rebuilt).

Melville is well established as the lone wolf of the French cinema. He works hard at it and likes to say that it isn’t so easy to make an enemy a day. But solitude is not so hard when you know how to use it, reading or watching films. For Melville is an insatiable film addict and an indefatigable spectator. It’s not unusual to find him at 5 o’clock in the morning, watching an American film either in his own home or with some equally fanatical friends. Ever since his first film, Le Silence de la Mer, Melville has asserted his independence of the French industry and its product. He is his own producer, for he likes to be ‘responsible for his own mistakes’. And his isolation, which he cultivates as much from pride as from humility, enables him to view himself, as well as other people, wth shrewd appraisal.

Melville slips into his black raincoat, puts on his huge stetson, and leads us to his Chevrolet. He looks exactly like one of his own heroes – or more accurately, his heroes look exactly like him.

This feature was originally the cover story of our Summer 1968 issue

You have said that all your films to date were merely rough drafts. Is this also true of Le Samourai?

Certainly. I’m incapable of doing anything but rough drafts. Each time I see one of my films again, then and only then can I see what I should have done. But I only see things this clearly once the finished print is being shown on the screen everywhere and it’s too late to do anything about it. I have never been satisfied by my films, never.

You have often been described as ‘an American director’, sometimes with implied criticism. How do you feel about this?

I have been tidied away once and for all in a drawer in a sort of filing cabinet under the label ‘American’. This is quite wrong. I’ve put up with it for five years, but now I’ve had enough: I am absolutely not an American director. If by this people mean that I make my films with enormous care leaving nothing to chance, my answer is that the great Japanese directors work the same way. Anyway, I feel much more Japanese than American. Le Samourai is a Japanese film, as the title suggests.

The most important quality needed by a film director – or as I prefer to say, a film creator [un createur de cinema] – is the ability not to work through his intellect, otherwise he ceases to create a spectacle. He must also have a feeling for observation, memory, psychology, and a fantastically acute sense of sight and sound. He must have the instinct of a showman. A film is a spectacle, just like the circus or the music-hall; when it’s well done, it becomes a work of art. But the cinema as a whole is not an art yet – it’s going to become one. It is no accident that every writer I meet envies me my profession. Today, the cinema is the ideal form of literary creation, and young people no longer have a literary culture but a filmic one. This is something that would have seemed impossible 15 years ago.

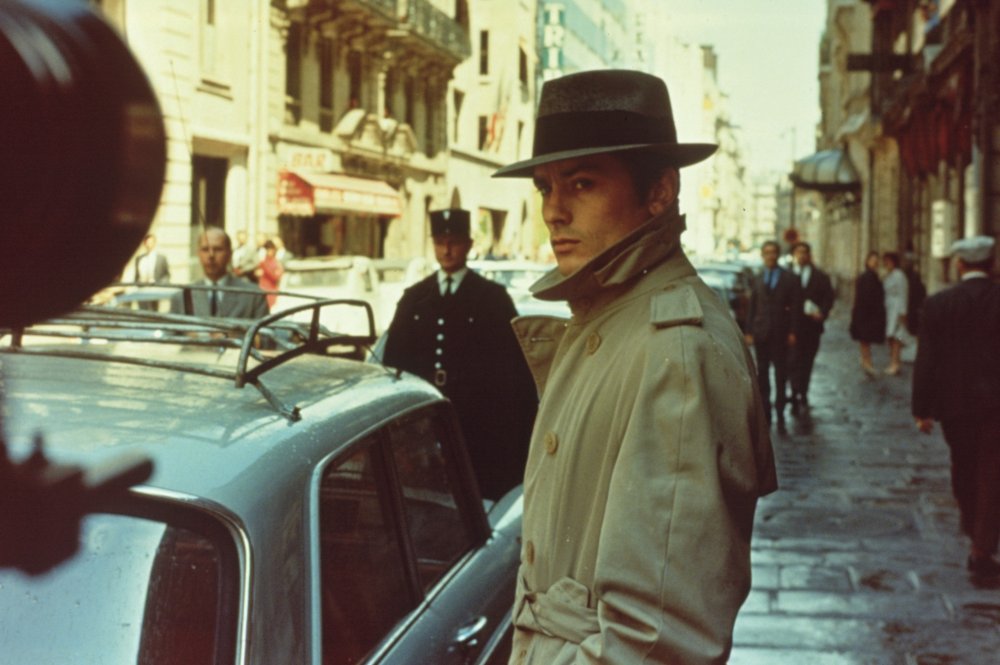

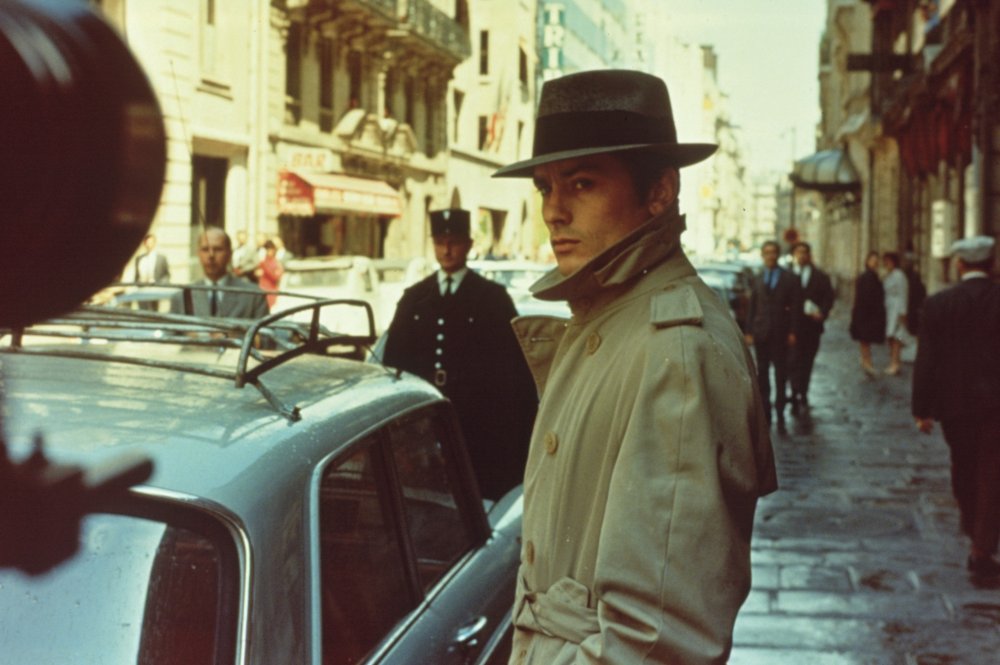

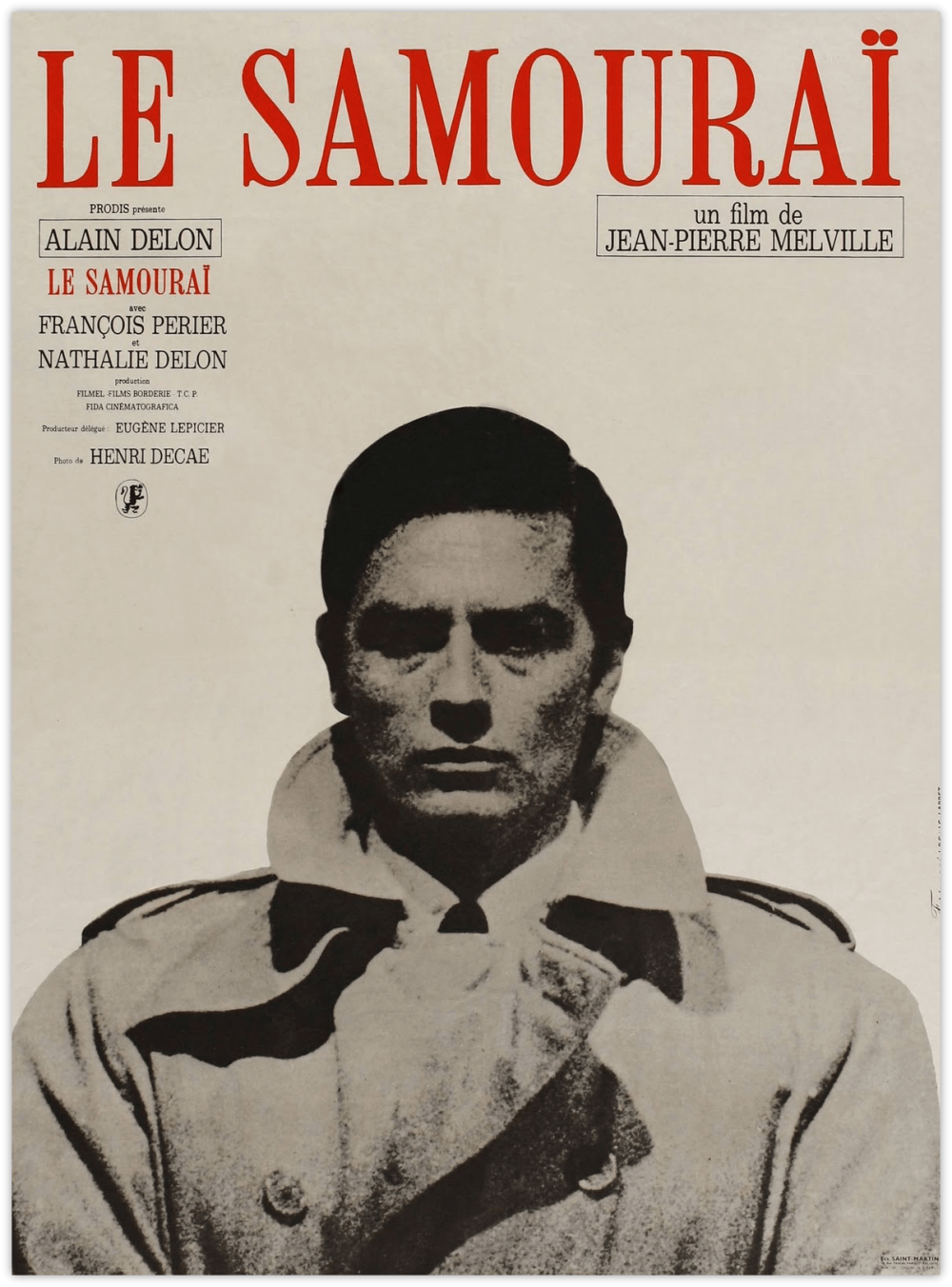

Alain Delon in Le Samourai

All your heroes wear a sort of uniform: hat, raincoat, etc.

I think the virile hero needs a horse, boots and saddle. As you’ve probably noticed, they’re not exactly common on the streets of Paris, but at least you can give him a hat, a raincoat with a belt and a collar that can be turned up, and a button to do up when it rains. It’s a man’s get-up, an echo both of the Western and of military uniform. And there are the guns too, it all springs from the barrack-room. Men are soldiers, women may be by accident… Between the ages of 12 and 14 I was both formed and deformed to a great extent by the first American gangster novels. So I’d be quite happy to have you say I make gangster films, inspired by the gangster novels, but I don’t make American films, even though I like the American films noirs better than anything.

L’Aine des Ferchaux is a dream of America rather than America itself?

Of course. Starting from one of Simenon’s novels I presented a particular aspect of America that I’m rather fond of. The Americans, I might point out, decided I was very anti-American, certainly a Communist. Not that that matters. I’m very fond of America. What would be really great would be if there was no one living in it, nothing there. Because of course no one could possibly replace the Americans. The country would be like a vast museum where you could just wander around. When I made Deux Hommes a Manhattan I was writing a love letter to New York, and my story takes place at night because that is the time for writing love letters. Any story set in a big city should start at about six in the evening and end with the dawn.

Your heroes never grow old. Even when adult, they remain essentially adolescent.

That’s my own particular hang-up. I think I’m still 18 years old. Outwardly, of course, I behave like a sensible gentleman of 50, but inside I’m still 18, I haven’t changed. I think that is man’s special prerogative. Moreover my studios on the rue Jenner (which I’m going to have rebuilt) are an adolescent dream.

You are often reproached for the improbability of your heroes, who are very easy to recognise.

It’s because I don’t want to situate my heroes in time I don’t want the action of a film to be recognisable as something that happens in 1968. That’s why in Le Samourai, for example, the women aren’t wearing mini-skirts while the men are wearing hats – something, unfortunately, that no one does any more.

I’m not interested in realism. All my films hinge on the fantastic. I’m not a documentarist: a film is first and foremost a dream, and it’s absurd to copy life in an attempt to produce an exact re-creation of it. Transposition is more or less a reflex with me; I move from realism to fantasy without the spectator even noticing.

Le Samourai describes several parallel worlds which never overlap but merely brush against each other from time to time – the Delon and Perier characters in particular. Perier is a logical character, very Cartesian, very French; Delon is a mystery, a complete enigma. We don’t know who Delon is, what he used to do, where he came from, how and why he has become a hired killer.

This was deliberate on my part, because I can’t stand the sort of film which tries to place a character by having him announce “I was with the army in Indochina and later in Algeria, I used to kill for the Government’s profit and now I’m killing for myself,” etc.

Melville’s 1950 adaptation of Jean Cocteau’s novel Les Enfants Terribles

From Les Enfants Terribles right up to Le Samourai, there’s a certain affinity between your work and Cocteau’s.

Jean Cocteau was one of the greatest writers France has produced in the last 50 years. You have only to read or re-read his plays, poems, novels and essays to be convinced of that.

He unquestionably had a formative influence on several generations and on mine in particular, because in 1931, when Les Enfants Terribles was first published I was a pupil at the Lycee Condorcet and I used to pass ‘the ‘cite Montier’ four times a day. That was how I discovered Cocteau’s universe.

My films are different from his but there is undeniably a certain intellectual affinity between us. That’s probably why he asked me to make Les Enfants Terribles. We had a lot of tastes in common.

I adore the beginning of Orphée, it’s wonderful, quite fantastic. The second part isn’t good, for reasons that I’d rather not go into, although it does have some very fine things in it: the tribunal, the passage from life to death through the mirror, and so on. Casares had the best role of her career in it and Perier was brilliant. As soon as I saw him in Orphée, I was determined to have him in one of my films.

You’ve made three films with Belmondo (Leon Morin, Pretre, Le Doulos and L’aine Des Ferchaux) and, up till now, only one with Delon. What do you think of these two?

They’re the only two jeunes premiers in the French cinema. So I’m forced to make comparisons, but what I say in favour of one doesn’t imply any criticism of the other. Belmondo can play parts that Delon would be incapable of playing, and vice versa. They complement one another quite admirably.

I wrote Le Samourai for Delon, with him in mind and inspired by him. Of course, if I were to write an original screenplay for Belmondo, Delon could not possibly play it. Belmondo is remarkable in Leon Morin, Pretre, and Delon in Le Samourai. Neither of them could possibly replace the other. The two films are about the same character played by very different actors. Delon is a remarkable actor, and remarkably professional.

I don’t like characters to be explained through a few ‘tics’, although Delon copied two of mine for Le Samourai – the gesture of running two fingers over the brim of his hat, and the way of wearing his watch on his right wrist with the dial turned in.

Similarly, I didn’t want to be explicit about the relationship between Delon and Nathalie. It’s of no interest to know whether they are lovers or not. Their relationship has the same ambiguity as the one between Lino Ventura and Christine Fabrega in Le Deuxieme Souffle. They could be brother and sister; it’s the ‘enfants terribles’ side of Cocteau.

Nathalie Delon is so like Elizabeth and Alain so much like Paul, it’s extraordinary how alike they look.

Jean-Paul Belmondo in Le Doulos (1963)

In Le Doulos, Le Deuxieme Souffle and Le Samourai one finds the same recurring relationship between gangster and police chief: Belmondo, Ventura and Delon as the gangsters, Desailly, Meurisse and Perier as the policemen.

For me, the police chief is Destiny. That’s how the character has to be, for he represents inescapable destiny: he doesn’t personally execute the gangster, but he does set the machinery in motion.

In the last scene of Le Samourai, Delon does not want to kill. He removes the bullets from his gun, then he goes back into the bar, into the trap which has been set for him, and he kills himself, he commits hara-kiri.

From the outset, the black woman in white is the incarnation of Death, with all the charm that death can have.

At one point in Cocteau’s Orphée, Maria Casares said “I should not mind being changed into a pillar of salt,” and her black dress became white – and, for Cocteau, Casares represented Death. The character of Jeff Costello (Alain Delon) in Le Samourai is in love with his own Death. In the first shot he’s stretched out on his bed, already ‘laid out’, already dead at that moment, and everything follows.

After the success of Le Samourai, you have several projects lined up, and right now you’re preparing La Chienne, a remake of Jean Renoir’s 1931 film and of Fritz Lang’s Scarlet Street (1945).

It will not be a remake. There’s an idea in the original book that interests me, and that’s all.

The film I shall probably make from La Chienne will be nothing like the novel and still less like the films by Renoir and Lang.

Both these films were made from an adaptation written by Mouezy-Eon, and not from the original book by La Fourchardiere. (As you may know, because Mouezy-Eon acted as an intermediary in the sale of the rights to Braunberger and Richebe in 1931, his name has to appear on the credits of any film based on La Chienne by La Fourchardiere.)

I should very much like to do it with Lino Ventura. What interests me is the principle behind the original book which, in its introductory note, describes the characters as “He, she and the other, the eternal triangle.” But my characters will be nothing like those in the novel. ‘He’ is an extremely timid person who opens the first chapter with the words “Tonight, something happened to me … ” I shall keep this sentence in my film, but instead of continuing, “It’s the first time in my life that anything has happened to me,” he will say “Although God knows enough has happened to me already…”

You see, I’m turning someone who’s essentially a victim – like Professor Rath in The Blue Angel, for instance – into a man who’s tough, who has been through it all, possibly an ex-gangster or a nightclub owner, I’m not sure. In any case, he will be the kind of man you can’t easily imagine falling in love at first sight, or with an average sort of girl.

What interests me is that ‘he’ narrates the first sequence, ‘she’ narrates the second sequence, ‘the other’ the third, and then the cycle starts all over again. Each character describes things from his own point of view – describing not the same scene, but the next one in sequence.

That’s how I envisage my version of La Chienne. If I don’t start it right away, I may make a spy film from a novel called The Packard Case. If it comes off the way I hope, it will be the kind of film that should have been made from John Le Carre’s excellent book The Spy Who Came In From the Cold. That’s one remake I’d be happy to do, for I found Martin Ritt’s film really very bad and rather grotesque.

A Parisian in America

I remember one day when I was in America making L’Aine des Ferchaux. We’d been shooting all day and had driven for half the night before stopping at a roadside motel.

As soon as I got to my room, I unplugged the Musak and switched on the television. Mr. Smith Goes to Washington came on, directed by Frank Capra, with James Stewart and Jean Arthur! It was two o’clock in the morning and I watched it.

Needless to say I slept wonderfully afterwards. Next morning, I opened my window and saw an exquisite landscape: a tiny valley with a river, and a wood on the far side of it. It was raining. But the moment I opened the door, the rain stopped and brilliant sunlight shone on to the wood. I had such an overwhelming feeling of well-being and happiness that I moved a table over to the window and started to write a book, which I’ve never finished…

You once said “Writing is a real art.” You did start to write a book of reflections entitled Du Createur du Cinema, and also a novel.

Both are burned. I had already written about 300 pages of the novel, which would have been between 400 and 450 pages long. It started in 1941, in America of course, and ended during the Eisenhower regime; it was a study of five or six characters. I don’t think I shall rewrite it, but I do intend to rewrite my book on the cinema.

You have said that you’d love to make a film in America – an American film – perhaps either a war film or a musical comedy?

Yes, I’d very much like to make a war film, but I can’t make it out of my own experiences. That film would be censored and would never get through.

It would have to be based on a script or a novel, on something ‘invented’, because I could never put in all the little incidents, all the things I saw. I could go on talking all night about them.

I made Le Silence de la Mer because I was concerned with that sort of problem, but even there I had to stray a long way from the truth. Of course war is against an enemy, but it’s within your own ranks as well. I’d like to deal with this sort of internal war in a book, which would be easier.

Let me give you one or two examples: on August 19, 1944, on the outskirts of Toulon, five Germans came out of the forest with their hands up and started walking towards our 13.35, a light tank. They wanted to surrender. I was the only witness, which made it difficult when the top of the turret opened and an N.C.O. signalled the Germans to come closer.

By the time I realised what was going to happen, it was too late: I was just about to call out to the Germans when the tank started moving and rolled right over them. Like an idiot I took out my revolver, then the N.C.O. closed the turret and turned his machine gun on me.

A pleasant little wartime anecdote, isn’t it? I could also tell you the true story of the ‘Ciociara’. It wasn’t really the Moroccan soldiers who had raped the Italian girls, if you get my meaning.

Or there’s the story of the N.C.O. who had a great time using his American rifle to pick off Italian peasants working in the fields. And so on…

On the other hand, I have some very moving memories. One day, I remember, I was near the surgical block. The surgeon was a woman, a slightly masculine woman who smoked dark tobacco. She was wearing a butcher’s apron, all red, as she used it to wipe her hands on after each operation. Then she’d smoke a cigarette, and go back in to start operating again…

It was pretty unusual anyway having a woman surgeon in a unit so near the enemy lines. At one point, they brought out a young boy from my division and set him down with a blanket over him, and I saw he’d lost one of his legs.

They put him down under an apple tree in blossom, it was springtime, and I could see that he was going to die. So I did something that I must have remembered from a film – you see how the cinema can haunt you? – I lit a cigarette and placed it between his lips. He looked at me for a second, took a couple of drags on it and died.

Imagine the springtime in the Italian countryside –we were not very far from Florence, it was a sunny day, and there was this kid who died at the age of 20. Reality has always been way ahead of the cinema and its war films: one can only make war films because incidents like this are true, or were true at a particular time.

Le Silence de la mer (Jean-Pierre Melville, 1948)

Have you had many offers to film in America?

Yes, but I’m the French producer who turns down American contracts. I’ve refused 54 offers, as well as innumerable projects that never got anywhere.

I’ve only made ten films so far, for since I’m not recognised by the industry – you were talking about my isolation a little while ago: since the age of 21 I’ve been shut up in a kind of strange ghetto, I’m not very sure why – I’m hesitant about signing an American contract because I don’t want to be a director at the beck and call of an American company. But I wouldn’t mind being my own producer in France, financed by an American firm.

I don’t know if you’ve ever read an American contract, but it’s terrifying, you’re completely imprisoned by the small print.

Take this clause for instance: “You hereby undertake that during the making and distribution of the film you will at no time conduct yourself, publicly or privately, in any manner which offends against decency or morality, or causes you to be held in public ridicule, scorn or contempt, or causes a public scandal; or which would be prejudicial to the film, theatre or television or radio industries in general. In the case of such conduct, the company may, prior to the completion of the work contracted, terminate the contract, without any further obligation of any kind…”

It isn’t possible to work under such conditions. Suppose I sign a contract like that and start shooting, and for some reason or other the star decides he isn’t satisfied with my work; so the company looks into my past and discovers that I was once a homosexual or a thief or a member of the Communist Party, and they can kick me out just like that.

I think it’s shaming to sign a contract like that and insulting to suggest that anyone should. If I sign anything, I want to impose my own conditions. I don’t know what I shall do next, possibly a film with no stars, very low budget..

Is this just contrariness? Because right now you’re in a position to ask for whatever you want.

Yes. I’m tempted to make a film with the kind of freedom you can only get with a technical crew reduced to a single operator and one or two other people.

While I was shooting the tailing sequences in the Metro for Le Samourai, I remember inwardly cursing the person who’d written the script without considering the difficulties involved in shooting the scene – and then I remembered I’d written it myself.

There was only one way to shoot it, with a hand-held camera and without any trickery. We shot it with just the ordinary lighting in the Metro, and it was very hard and very tiring. We had to get on a train, stay on for three or four stops, then get out and have the camera ready in the place where we knew Delon was going to appear in the doorway, be careful not to have a shadow hide his nose, and so on.

It took us a full week of hard, crazy work. I was also the stills photographer, as well as doing all the sets, colours, etc.

Alain Delon in the Paris Metro in Le Samourai

The way you’ve used colours makes them all tend towards grey.

Yes, I’ve always liked that particular tonality. I think one always needs to cheat and choose – to make a colour film look like black and white. For instance, the bank notes at the beginning of the film are in black and white and not in colour; they’re simply photocopies of bank notes, and if you look carefully you can see that the labels on the bottles of Evian water in Delon’s room are black and grey, and not red, and so is the packet of Gauloises.

What do you think of the American cinema at the present time?

1 like Arthur Penn very much, I’ve always said he was a man with a lot of talent.

I’ve just seen Bonnie and Clyde and it’s an unusually beautiful film, even though I don’t much like the way the style changes from one sequence to the next.

Two of the actors in it gave the most stunning performances I’ve ever seen – Michael J. Pollard as Moss, the young service station attendant, and Gene Wilder as one of the minor characters called Grizzard.

As for Faye Dunaway, she really is very beautiful. Warren Beatty I preferred in Mickey One. But one shouldn’t be too hard on him: he’s capable of very pleasant surprises, as in Lilith, for instance, where he is superb. But then Lilith is a wonderful, a really remarkable film which I’d defend against all comers.

One evening in New York at a reception in honour of Mastroianni, I suddenly noticed a little man with curly fair hair standing in the corner of an enormous room crammed full of celebrities. It was Robert Rossen. I went over to talk to him about his films.

He was very surprised to discover that his work was known so well in France, and he asked who I was and what I did. When I said that, like him, I made films, he looked even more surprised. He wanted to know what I had made and I began by mentioning Le Silence de Ia Mer. He’d never seen it. Then, when I started to talk about Les Enfants Terribles, he burst out, “I’ve seen it, I’ve seen it several times… but you didn’t make it, Cocteau did!”

Romain Gary and Jean Seberg told me that when he was making Lilith, Rossen developed a kind of stigmata. The blood kept penetrating his skin – a completely unknown disease which irresistibly recalled the stigmata of the Catholic religion. His shirt was always stained with blood.

Of course I didn’t know this at the time, but when I saw Lilith I said to my wife, “We’ve just seen Robert Rossen’s last film. When a man achieves that degree of perfection, he has to die. As Becker did after Le Trou.” And now he’s dead.

When I told Lino Ventura that Rossen was a little old man over 60 years old, he just couldn’t believe it. “What? The man who made The Hustler?” He was right, of course: The Hustler was the work of a 30-year-old.

Do you think you will make any more ‘detective’ films?

Yes, of course. I’d like to make a film lasting three hours with an interval for the sale of ice-creams, because that’s what keeps the cinema going. The first part would tell the gangsters’ story. You might think it was over, but the second part would start with a policeman arriving and the story would begin all over again.

I should also like to make a film with Jean Gabin and Lino Ventura. For me, Gabin is one of the finest actors in the French cinema and I’d be delighted if he’d agree to work with me.

I’ll tell you just the beginning of the film I want to make. I would start from a basic police situation, and turn it into a Kafkaesque one. I’ve already written the story, very succinctly.

Lino Ventura is appointed director of the Police Judiciaire and he takes over his new office. You know that the head of the P.J. doesn’t necessarily have to be a policeman, he’s a kind of high-grade administrator. Well, he starts the job on a Monday morning. The Prefect of Police phones him and says, “Please come to my office, it’s just across the Boulevard du Palais, there’s someone I’d like you to meet.”

Ventura leaves his office, crosses the Boulevard du Palais, gets to the office of the Prefect, and is introduced to Gabin, who’s the ‘Inspecteur General de Service’, a kind of police controller, the police force of the police force. It’s a branch of the service few people know about – not secret, but since it’s reserved exclusively for policemen, we the uninitiated never hear about it.

In the course of the conversation – which is not without its philosophical pretensions – Ventura says, ”I think there are more innocent people than guilty.” Gabin replies, “That just shows you have no police experience. You’ll learn that there are only the guilty. It’s not that there are more guilty than innocent, or that no one is innocent: they are all guilty.”

Ventura says “You’re joking, etc.” The Prefect, who is a man of the world, joins in the conversation, which becomes very light and trivial, and so it ends. They exchange pleasantries and go their separate ways. The ‘Inspecteur General de Service’ goes back to his office, calls his assistant and says to him, “Get me the dossier on the new director of the P.J.”

You can imagine the rest…