Book excerpt: How the Liberal campaign team helped Justin Trudeau survive arguably his worst scandal of his political career

Article content

This is an excerpt from The Prince: The Turbulent Reign of Justin Trudeau by Stephen Maher. It tells the story of longtime Trudeau adviser Gerry Butts’s return to the prime minister’s campaign team, just as Justin Trudeau faced perhaps the worst scandal of his career.

Article content

After testifying in the SNC-Lavalin affair, Butts had been licking his wounds and reconnecting with his family after the brutally long hours he had worked in the PMO. His wife, Jodi, joked she should send Jody Wilson-Raybould a present to thank her for engineering her husband’s exit from politics. But on a trip to Tuscany to celebrate their twentieth anniversary, he told her he thought he should go back for the 2019 campaign. She reluctantly agreed. “You know what? If you don’t go back and they lose, you’re going to blame yourself for the rest of your life. So just go do it. But you’ve got to promise me on election night it’s all over.”

Advertisement 2

Article content

Butts returned as a senior adviser for the campaign, to strategize, as he had done in Trudeau’s successful election of 2015 and in earlier elections for Dalton McGuinty in Ontario. On his first day back, Brian Clow, the issues manager on the campaign, told him that BC Liberals had heard that a reporter was making inquiries about a yearbook photo involving Trudeau. Anna Kodé, a plucky twenty-two-year-old cub reporter with Time magazine, had heard about a brownface picture of Trudeau. She set out to track it down and eventually found it through the father of a university classmate, Vancouver businessman Michael Adamson. He had a family connection to West Point Grey Academy, where Trudeau had taught. Adamson had a copy of the yearbook. He was not involved in politics and didn’t want to be in the public eye, but he thought Canadians should see the picture before the election.

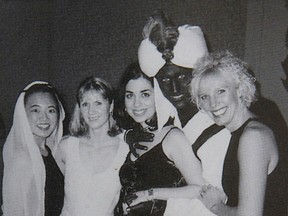

The photo had been taken at an “Arabian Nights” party Trudeau attended when he taught drama at the school in 2001. It shows him standing with four women, all smiling and enjoying the party. He is wearing a robe and a turban decorated with feathers and a large jewel.

Advertisement 3

Article content

The picture came from The View, the private school’s yearbook, which Trudeau helped produce. It includes several other pictures of him too, wearing a kilt, a bowler in the style of Charlie Chaplin, and a tux, James Bond–style. They are pictures of a popular, exuberant, attention-seeking young man.

The photos are all black and white, but the troublesome picture showed him wearing dark makeup on his face and hands. In fact, it was blue. He was dressed as Aladdin, from the 1992 Disney animated movie. Though not prime-ministerial, it was not particularly shocking. If it was the only picture, he could have pointed to the context and shrugged it off. But it was not the only picture. In February 2019, when reporters found yearbook pictures of Virginia governor Ralph Northam in blackface and a Ku Klux Klan robe, Trudeau had confided to Butts and Telford that he had also done blackface. “I knew the story was out there, but I had no idea there were so many,” says Butts.

Butts was pushing for the campaign to release the picture and get ahead of the story. “Guys, we’ve got to get this up there or it’s going to come out. And people are like, ‘No, maybe it won’t come out.’ Like, no. It’s coming out.”

Article content

Advertisement 4

Article content

The team wouldn’t budge, and Butts, frustrated, went back to his office. Before long, Zita Astravas, media relations lead for the campaign, who was not in the loop, came in, her face white with shock. “Time magazine just called me,” she said. “They have a picture of the prime minister in blackface.”

Butts burst out laughing. “Oh my God,” he said. “This could be the biggest disaster in the history of Canadian politics.”

Astravas, a savvy operator who had previously worked for Kathleen Wynne, broke the news to Kate Purchase, her boss on the campaign. “We often called her Kramer because she would burst into rooms,” says Purchase. “She burst into my office and said, ‘I have to talk to you right now.’ I was on a very important phone call and I said, ‘I can’t talk to you.’ And she said, ‘Hang up.’ So she told me and said, ‘They’re sending me the photo.’ ”

Purchase was flabbergasted. “All our reputations are now on the line.”

The senior people were worried how the young multicultural staffers in the war room would react to the news. Before the story broke, campaign manager Jeremy Broadhurst gathered them together and broke the news, followed by Butts. Some of them cried; others took time off to think things through. “Jeremy especially was really excellent and in a terrible position there, running his first campaign, having to go and do that,” says Purchase.

Advertisement 5

Article content

Senior managers also called in Vandana Kattar, who was working on multicultural outreach. “Here is this whole office full of very senior people,” she says. “I thought I was getting fired.” Butts was looking at her in a fatherly way. “I was like, ‘Did my husband get shot? What happened? Did my parents die? What happened?’ ”

Kattar liked the way they handled it. “I appreciated the warmth of my colleagues, who were all white and didn’t really know how to best support me but realized they had to support me somehow.” They needed her help, and they got it. She knew Trudeau well enough to be sure the photos didn’t reflect some kind of secret racism. “I didn’t think he was a racist. I thought, he was young once and didn’t know better. I have known him since 2009. I have worked for him since 2012 or 2013. We went on tour driving in my 2005 Chevrolet Cobalt together. And that really brings you together.”

After a rally in Truro, N.S., the senior people got on the phone to Trudeau and strategized how best to handle the bombshell. They knew it would be a global story, a bad one, and he had to respond quickly. They threw questions at him—the kind of practice news conference that staffers do to prep leaders. Someone asked how many times he’d worn blackface. Trudeau didn’t know. That seemed like a tough thing to have to explain to Canadians.

Advertisement 6

Article content

After the meeting, Purchase was gloomy. This looked like the end. “Well, it’s been swell,” she said to Butts and Broadhurst.

The Conservatives had found a video of Trudeau in his early twenties clowning around in actual blackface, almost minstrel-style, from when he worked as a whitewater rafting guide on the Rouge River in Quebec. The Conservatives gave it to Global News, but they hadn’t broken the story yet.

He wanted to have the best costume at the Arabian Nights thing at West Point Grey, in India, at Halloween

When Trudeau had been a student at Brébeuf, he had performed “Banana Boat (Day-O),” the Harry Belafonte classic, on stage in blackface. I am told that he also wore blackface at McGill on Halloween in 1993, going out as Ted Danson, who had offended Americans that year by wearing minstrel-style makeup to a comedy roast (at the instigation of his then girlfriend, Whoopi Goldberg, who is Black). Any one of the pictures could perhaps have been waved off, dealt with, rationalized. Together, they posed a problem that could not be explained away.

It is surprising that none of the photos had surfaced earlier. If they had come up during the 2015 election campaign, for example, they would have reinforced the Conservative message about Trudeau and raised doubts within his multicultural progressive coalition. He likely would not have won the election. “The opposition—Conservatives and NDP—they should have found this,” says Clow. “They didn’t.”

Advertisement 7

Article content

***

TERESA WRIGHT, A JOURNALIST from Prince Edward Island, was on the media bus covering the 2019 campaign in Nova Scotia for the Canadian Press. In Truro, she had noticed that Trudeau seemed “even more Energizer Bunny than usual, like feeding off the crowd in a way that normally he doesn’t. He was just extra happy. He took extra time shaking people’s hands to get up to the stage.”

After the event, the reporters filed their stories, did their standups, and got on the bus for Halifax, where they were to board the plane for Winnipeg. No events were scheduled that night. Usually, that would mean it was time to break out the beer. But it was not party time: “All the staffers were super somber.”

Glen McGregor was on the bus for CTV when the story broke. “All of a sudden, everybody’s phone starts going off. And it’s like a rock concert, when people hold their phones up.” The assignment desks were looking for the reporters on the bus to match Time’s explosive scoop. McGregor was trying to figure out how he had been beaten on the story. “Surely somebody would have gone and pulled his high-school yearbook photo, because that’s what you do. But then I realized nobody thought to pull the high-school yearbook at the high school where he taught.”

Advertisement 8

Article content

Nobody had by then told the reporters that Trudeau would respond before the plane took off for Winnipeg. McGregor talked to his colleagues from other outlets and decided to push the matter. “I walked three or four rows back to where [press secretary] Cameron [Ahmad] and the cameras were, and I said, ‘Before we leave Halifax, we need your guy or we’re not getting on the plane.’ And Cameron’s like, ‘Yeah. We know.’ ”

On the plane, Trudeau scrummed from the front of the cabin, wearing a suit, frowning, apologizing. “I deeply regret that I did that,” he said. “I should have known better, but I didn’t.”

The journalists, having been scooped by their American counterparts, were not going to go easy now. The normal rules—where they take turns and wait for follow-ups—were out the window. “It’s just a mob scramble of people shrieking questions,” says McGregor.

Trudeau didn’t say much, repeating his apology. David Akin asked if he would resign. Trudeau was experienced enough not to say, “No. I won’t resign,” which would have been the media clip rather than the obvious one of him apologizing.

Advertisement 9

Article content

Even if Trudeau handled it well, it was a nightmare. The story went viral around the world. Global sent Kate Purchase an image from the video they had, of Trudeau in actual blackface from a rafting camp. The staffers couldn’t tell if it was actually him, so she sent it to the plane for Trudeau’s confirmation. Global put the story out, meaning there were now at least three incidents of Trudeau in blackface. He was a global punchline. The election was up in the air.

For young racialized people on his staff, the story was especially painful. Not only had their leader been shown to have done something, repeatedly, that they found hard to understand, but the reporters shrieking at him were all white. “Obviously, as soon as blackface broke, people tweeted pictures of us,” says Wright. “There was [a picture] of us on the plane. And they’re like, ‘Wow, look at the press. Those are all white people.’ And I thought, ‘Oh, crap.’ ”

The Press Gallery is what you might call a lagging indicator in Canadian society. It is less diverse than the institutions it covers, largely because the media organizations who do the hiring have been financially struggling for decades, shedding rather than adding jobs while other institutions were welcoming newcomers who better reflected Canada’s growing diversity. On expensive leaders’ tours, all the outlets tended to send only their most experienced people—and they in turn represented the industry as it was in the past.

Advertisement 10

Article content

It was a long, grim flight to Winnipeg for the Trudeau people, McGregor says. “They don’t know really until the next day if their campaign is fucked, if the Trudeau experiment is over.”

When explosive news breaks, it is not always clear how voters will react. The most famous Canadian example is the “Shawinigan handshake,” when Prime Minister Jean Chrétien throttled protester Bill Clennett at a 1996 Gatineau protest. His staff was terrified he would be seen as a thug, but the polls showed that people liked it, and it is now part of Chrétien’s schtick. The big question for staffers on the Liberal plane was whether Trudeau would be cancelled. He worked the phones all the way to Winnipeg, apologizing, asking for advice.

Recommended from Editorial

Jagmeet Singh, who had been struggling to connect with Canadians since taking over the NDP after Thomas Mulcair’s exit, released a note-perfect video on social media, pointing out that the story would be painful for people who had experienced racism and been marginalized by white bullies. “When I was growing up, I fought racists. I dealt with them myself and I fought back. But I got a message from a friend and it reminded me that there were a lot of people who couldn’t do that . . . And I think it’s going to hurt to see this. It’s going to hurt them a lot.”

Advertisement 11

Article content

Singh’s video was the ideal illustration of why representation matters, why Canada’s political class must reflect the country. Singh is a Brampton lawyer who drives a BMW sports car and wears Rolexes and tailored suits. His advocacy on economic justice issues often seems hollow, as though he is delivering lines by rote. He doesn’t have the effortless command of legal and constitutional issues that Mulcair had, and he sometimes gets himself in trouble, particularly in Quebec, where voters are not ready to warm to a leader in religious headgear. The party had sixteen seats in Quebec at the time, and Singh was going to lose all but one. But when the blackface video dropped, he helped Canadians understand why the pictures were problematic. It gave his struggling campaign a boost and made the election more competitive. The Conservatives typically do well in Canadian elections only when the NDP is doing well, because of the vote splits on the left in tight ridings.

For the Liberals, especially Black Liberals, the incident was a gut punch. They networked frantically while they tried to figure out how to react. Greg Fergus, the Liberal MP for Hull–Aylmer, had founded the Black Liberal Caucus, a group where Black staffers and MPs from across the country met on an equal footing to discuss Black issues. They had worked with Trudeau to get the picture of Viola Desmond—the Black woman jailed in Nova Scotia in 1946 after refusing to leave her seat in a movie theatre—put on the ten-dollar bill. As the story was breaking, Butts set up a call with Fergus and Trudeau. Fergus told the prime minister he had his back.

There was a distinct generational divide. “Anybody over the age of forty had the exact same reaction I had. ‘This is shit, but, you know, move on. We know where he is at,’ ” one prominent Black Liberal told me. “And under thirty, the reaction was ‘Who the hell does that?’ ” Some of the conversations were tense. “Look. This is your come-to-Jesus moment,” one Black Liberal recalls saying. “Are you in or are you out? Because if we shit on him, we lose this.” Barack Obama must have reached a similar conclusion, because he tweeted an endorsement of Trudeau as the campaign entered the home stretch.

Advertisement 12

Article content

In Quebec, where American cultural dynamics have less force, the story did not resonate in the same way as in English Canada. Haitian Canadian novelist and professor Dany Laferrière laughed at it in TV interviews, accusing Trudeau’s opponents of attacking him hypocritically. Trudeau had been silly, he said, not racist.

The next day, in Winnipeg, Trudeau did a long scrum in a downtown park, accompanied by Robert-Falcon Ouellette, an Indigenous MP. He talked for forty minutes, until journalists ran out of questions. He made an abject apology: he didn’t excuse himself, didn’t say he was sorry if people were offended. He said that what he had done was wrong and that he should have known better. It was wrong because of the harm it does to people who have dealt with discrimination. “I didn’t see that from the layers of privilege I have,” he said.

By the end of the news conference, there was not much that anyone could say that Trudeau had not said himself. Reporters eventually cornered him into admitting that he didn’t know how often he had worn blackface, but otherwise the event was free of news. At one point, when he asked for forgiveness, people in the park spontaneously applauded.

Advertisement 13

Article content

Cameron Ahmad was relieved to hear the people clapping. He was twenty-seven, the child of Pakistani immigrants. For his generation, the idea that someone would don blackface was hard to swallow. He knew Trudeau, whom he considers the “most inclusive, diversity-loving prime minister we’ve ever had,” but was finding it hard to absorb the whole thing. Ahmad believed Trudeau’s earnest apology was genuine, and it helped clear the air. Party canvassers and pollsters soon learned that many Liberal voters felt the same way. The campaign pivoted quickly to guns, flying into Toronto to announce a ban on “all military-style assault rifles, including the AR-15.”

Trudeau was able to skate away from this scandal, but it would follow him around for the rest of his career. One of the things that his critics—especially white men of a certain age—find most galling about him is his tendency to virtue signal, letting on that his opponents should move closer to enlightenment by emulating him in mouthing pious bromides. Yet he seemed to have bullied an Indigenous woman in the SNC-Lavalin affair and now it had been revealed that he’d repeatedly worn blackface, like a 1960s Alabama frat boy. His team would have automatically rejected prospective candidates with blackface pictures in their background. He, in contrast, was protected, as he said, by layers of privilege. He is a prince, and the rules don’t apply to princes.

Advertisement 14

Article content

Before the story broke, Telford had mentioned casually to reporters on the campaign that Trudeau liked to dress up, perhaps planting a seed so they would have some context in mind when the story came out—a subtle bit of spin, which works, like all good spin, because it is true. Trudeau has all his life sought the limelight. That desire is what makes him such an extraordinary campaigner and gives him the discipline to undergo the humiliations and travails that leaders must endure. Now he was paying for it. “He wanted to have the best costume at the Arabian Nights thing at West Point Grey, in India, at Halloween,” says one Liberal who has known him well for a long time. “He’s always got to have the best costume. Well, now he’s ruined that for himself.”

Excerpted from The Prince: The Turbulent Reign of Justin Trudeau by Stephen Maher. Copyright © 2024 by Stephen Maher. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster Canada, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

Our website is the place for the latest breaking news, exclusive scoops, longreads and provocative commentary. Please bookmark nationalpost.com and sign up for our newsletters here.

Article content