Until not that long ago, it was easy to praise cinematographer Roger Deakins as the man who didn’t need Oscars. To see through his eyes, to speak in his colour palette and luxuriate in his inky blacks – those were perks enough.

Now 70 and in the prime of his career, fresh from winning his second Academy Award for his work on Sam Mendes’s 1917, the Devon-born Deakins feels like an institution. Naturalistic without sacrificing technical discipline, he is capable of brokering an immediate connection between director and audience.

At the same time, he’s seen the future, long before many of us did: Deakins manipulated the image before it became fashionable, embraced digital, and now makes big-canvas work that feels decades younger than that of his peers.

Considering Deakins’s evolution means getting to know Joel and Ethan Coen – you might as well call him the third Coen brother after the dozen movies they have made together. But don’t confuse Deakins’s regularity with routine. If anything, their long partnership is founded on restlessness.

It begins in the mouldering hallways of a run-down Los Angeles hotel, where the neurotic screenwriter of Barton Fink (1991) toils at the life of the mind. Deakins crystallises the idea of something perfect just out of reach: a woman on the beach, her back turned to us, blocking the sun with her arm.

The subsequent films continue this quest. There’s pounding Midwestern flatness (Fargo, 1995; A Serious Man, 2009) and the desperate schemes of lonely men; elsewhere, we feel stifling heat (O Brother, Where Art Thou?, 2000; No Country for Old Men, 2007) and a kind of pent-up fury.

Just as memorably, Deakins has told the story, in images alone, of the invention and popularisation of the hula hoop (The Hudsucker Proxy, 1994, perhaps his most impressive sequence). He’s plugged us into the holes of a bowling ball rolling toward a strike in The Big Lebowski (1998).

And he’s taken this elastic-band tension – between deadpan irony and hopped-up anarchy – and brought it to other projects that needed it, notably Denis Villeneuve’s crushing cosmic tragedies (Prisoners, 2013; Sicario, 2015; and Blade Runner 2049, 2017, which earned Deakins his first Academy Award) and four wide-ranging, uncommonly intimate adventures directed by Sam Mendes (Jarhead, 2005; Revolutionary Road, 2008; Skyfall, 2012; and this year’s 1917). If it’s Deakins, we’re often looking at a psychological space, characterised less by light and dark than by an internal climate of mood.

A story has been widely shared of his early rejection from the then-new National Film School for not being ‘filmic’ enough. He made 1972’s second class after roaming the countryside and developing his eye. That’s either an example of a lesson learned, or a joke worthy of its own Coens comedy. Finding Deakins’s ten stepping stones is an impossible task, so let’s try to do it.

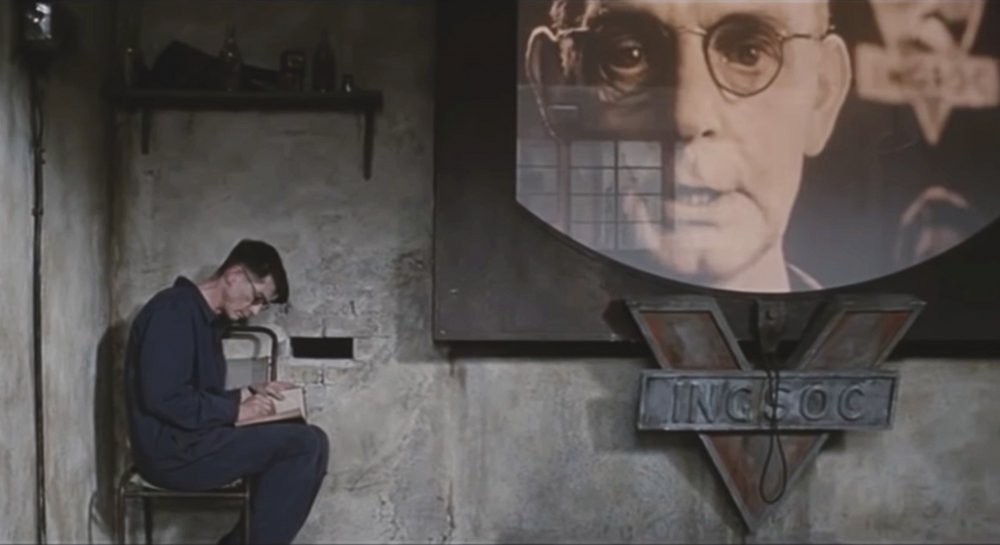

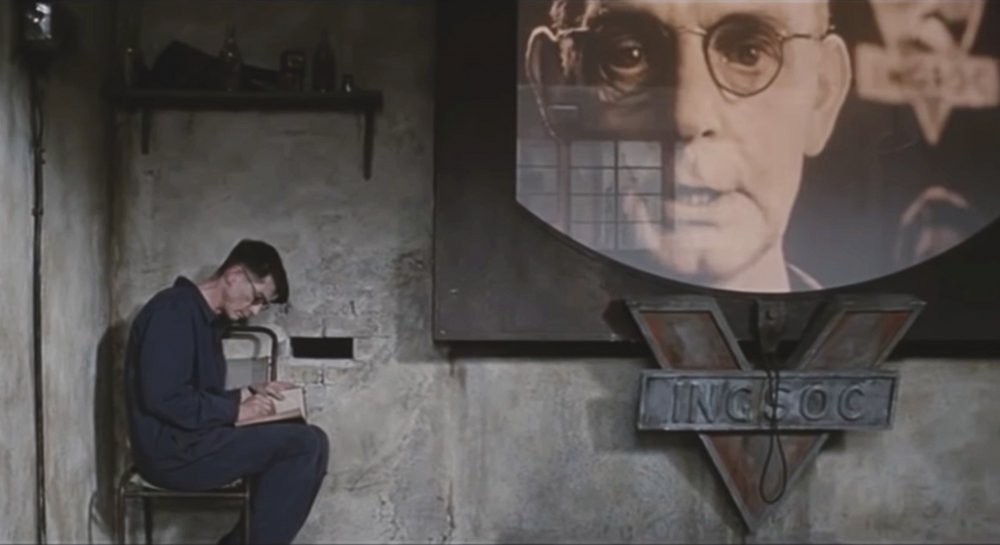

1. Nineteen Eighty-Four (1984): approaching Room 101

Strictly speaking, the career doesn’t begin here – there had been shorts and documentaries, a smattering of music videos (including Herbie Hancock’s ‘Rockit’) and Michael Radford’s austere 1983 wartime romance Another Time, Another Place. But with this striking, desaturated take on Orwell’s totalitarian nightmare, an artist is born.

Deakins and Radford had hoped to shoot in black and white, but the producers frowned. Deakins’s inspired solution was a revival of the tricky bleach-bypass process, a chemical overlay largely unused for decades (and later reclaimed by the cinematographer Darius Khondji for Se7en) resulting in shimmering, silvery blacks and muted, defeated blues. Every facet of Nineteen Eighty-Four’s greyscape is exquisite – as are its looming Big Brother telescreens, created in-camera for this pre-CGI production.

But the really memorable shot is a track behind Winston (John Hurt) down a dark, dingy hallway, until a doorway opens before him, revealing a lush, green paradise of the mind.

2. The Shawshank Redemption (1994): sweet freedom

Some would call this film’s lasting popularity mystifying, but that’s a trap: Frank Darabont’s prison drama endures because it’s a simple story well told. And when Morgan Freeman isn’t doing the telling (in sonorous voiceover), Deakins’s camera is the chief communicator, as is often the case with breakout movies, from A Man Escaped (1956) to Toy Story 3 (2010).

You would never call any of his shots methodical or rote. Rather, they chip away toward the goal of pure visual euphoria, which arrives with Deakins’s lightning-lit rainstorm. Escaped convict Andy Dufresne (Tim Robbins) is free after crawling his way through half a mile of shit, and the camera pushes behind him, wading through an outlet pipe’s waste water. Then we come around and rise, looking down at the transformed man, arms outstretched, reborn. The image would become Deakins’s first immortal bit of magic.

☞

3. Fargo (1995): great white north

Deakins had already collaborated twice with the brothers from Minnesota, first on their 1991 Palme d’Or-winning Barton Fink, then on their Preston Sturges-esque screwball The Hudsucker Proxy. Either film would be the high point of another shooter’s résumé.

But Fargo signals a further refinement of their shared visual language, here honed into something bone-dry and ice-cold. This is a movie with its own weather: violent gusts, blinding vistas and, in counterpoint to Carter Burwell’s lovely score, the crunch of windshield-scraping. Unusually for a comedy, Deakins supplies an overall mood of fatalistic, almost Herzogian irony; some of these characters are too soft to survive, expiring in a puff of down or a smear of red goo. Pregnant police chief Marge Gunderson (Frances McDormand) watches over everything like a hawk, but the moment that haunts us is Steve Buscemi’s “funny-looking” crook burying a briefcase of money in an unforgivingly banal field of snow.

☞

4. Kundun (1997): dreaming of the mountains

There’s a curious emotional distance to Martin Scorsese’s widescreen retelling of the Dalai Lama’s mid-20th-century exile from Tibet, impeccable though it is. To these eyes, that’s intentional, all the better to invite curious viewers to make an investment of effort into feeling the story: Kundun is an invitation to faith.

By this point, Deakins had a few scenic knockouts to his name – notably Bob Rafelson’s Mountains of the Moon, 1990 – but his documentarian’s eye is always roving and intelligent, never merely a conduit for empty voluptuousness. The final shot of Scorsese’s film is fascinatingly self-reflexive: a young man scans the Himalayas by telescope, seeking home and yearning to return. It’s a brilliant metaphor for this director’s career-long obsession with locating a spiritual dimension in the act of careful observation.

Deakins’s work here feels like perceptive film criticism; call it a crime, then, that it’s his only pairing with Scorsese to date.

5. O Brother, Where Art Thou? (2000): Deep South odyssey

Developed in tandem with the Coens’ ironic stillness (Fargo, No Country for Old Men), there’s a more playful mode here – not so much zany as uninhibited. O Brother, Where Art Thou? will serve to represent this brand of mania (with our apologies to superfans of The Big Lebowski and A Serious Man, both of them also shot by Deakins).

Revered by cinematographers, O Brother is the first live-action film to be extensively colour-corrected via computer; the Coens were after a sepia-tinted, old-timey softness and their Mississippi locations were far too verdant. For a reported 11 weeks Deakins redialled digital levels and inspected the yellowed results, a labour of love that would become commonplace in post-production. Ultimately, the effect is dreamy, uncanny and expressive in its own right – perfectly utilised when the Soggy Bottom Boys are lulled into submission by a trio of riverside sirens.

6. The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford (2007): great train robbery

If you were looking for a single sequence that contained everything Deakins did expertly, this rapturous locomotive heist in Andrew Dominik’s revisionist western would be it. A summation of Deakins’s career smuggled into an unsuspecting director’s movie, the scene showcases the cinematographer’s beloved bleach-bypass treatment from Nineteen Eighty-Four, adding extra texture to midnight blacks. Smoke and chiaroscuro swirl as the train’s stark headlight penetrates the tall trees; sparks fly from brake plates. Vignetted by a soft-focus blur on the edge of the frame, Deakins’s fable-like feel is breathtaking, propelling the story into the realm of Leone-esque mythology.

Dominik came into his project with an already impressive vision board, one influenced by pastoral painter Andrew Wyeth and films like Days of Heaven (1979). But his own director of photography one-upped him via an amalgamated style that harked back to the earliest silent cinema while feeling utterly fresh.

7. Skyfall (2012): showdown in the glass tower

If you make enough indelible images, the James Bond people come calling. Deakins was now the exemplar of a fully digital filmmaker, one who could add sizzle to even the oldest franchise. The Ken Adam-designed Bond productions of the 1960s and 70s were triumphs of elephantine modernism; Deakins brought back some of that classic-feeling size and swagger.

His signature contribution is a Shanghai gun-fu office fight shot in silhouette. Behind the combatants floats a building-wide jellyfish. (Don’t ask why an office façade needs a screensaver – it works beautifully.) Panes of glass splinter and Daniel Craig sulks; elsewhere in the film, a Macau casino beckons as Deakins serves up our hero on a floating platform of Chinese lanterns. He totally gets it, supplying de luxe exoticism and sharp edges in every frame.

8. Sicario (2015): battle on another planet

The Godfather cinematographer Gordon Willis earned the nickname ‘Prince of Darkness’ for his daringly underlit compositions (the epithet came from friend and fellow cameraman Conrad Hall, who himself dimmed the lights in such noirs as Road to Perdition, 2002).

Deakins mostly doesn’t get that glum. But has anyone topped the dusk raid in Sicario: tense, black-ops soldiering illuminated by the shallowest strip of fading orange light? The eerie, otherworldly shot emphasises the alienness of an undeclared war.

Embedded in tunnels or filming the campaign from high above the US-Mexico border, Deakins supplies the film with a near-abstract sense of surreality. The action is morose, furious and inconclusive; there’s a politics to the camerawork that went widely unmentioned at the time. Now it’s no longer subtext.

9. Blade Runner 2049 (2017): greetings from the future

If you were following along at home, this was the project that finally earned Deakins his first Oscar (after 13 previous nominations). Even more impressively, he emerged unscathed from the assignment with a distinct sci-fi psychodrama that somehow managed to please the fanboys – not bad for a sequel to a bona fide classic, one shot by the great Jordan Cronenweth.

Because it’s Blade Runner, there’s smoke. And rain. And interiors thick with dust motes. More subtly, Deakins captures the morbidity of a civilisation lost in mourning for itself.

His outstanding moment has sad-sack replicant ‘K’ (Ryan Gosling) approached by a Godzilla-sized pink hologram of a nude woman, sprung to life from a billboard: “Hello, handsome,” she coos, blinking soulless eyes. It doesn’t cheer him up. Their exchange is arrestingly strange and emotionally delicate – two ghosts in the machine.

☞ Blade Runner 2049 review: the future’s still questionable

10. 1917 (2019): entering the fiery city at night

Assembling a whole film as though it were a single shot doesn’t feel so impressive these days, particularly not to those of us who have seen the real thing in Alexander Sokurov’s Russian Ark (2002). But Deakins pulls off a dazzlingly phantasmagoric effect within Sam Mendes’s much-praised World War I drama which deserves all the attention: Lance-Corporal Schofield (George MacKay) emerges from his concussed state into an atmosphere of dread – a town reduced to rubble, mostly deserted. Fires and flares streak the darkness. A church blazes.

Once again, here is Deakins the nighttime master, turning pools of shadow into expressive black-on-black oils. Light slants across ruined buildings, rising and falling with every overhead blast; as a feat of coordination alone, it’s unmatched. (Deakins planned his moves using a scale model of the village.) We creep behind, pulled inexorably toward danger – or destiny. The sequence, exquisitely paced and executed, could be its own horror film.

☞

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/67/6f/676f8fd5-488c-4a04-a51a-191b03a543d8/main_20140720_2z9b2050_edmackerrow_fullres_web.jpg?w=420&resize=420,280&ssl=1)