Jewel Kiriungi,BBC News, Nairobi

Getty Images

Getty ImagesA severe internet outage that has hit several African countries – the third disruption in four months – is a stark reminder of how vulnerable the service is on the continent.

Questions are being asked about how the reliability of what has become an essential tool in nearly every aspect of life can be improved.

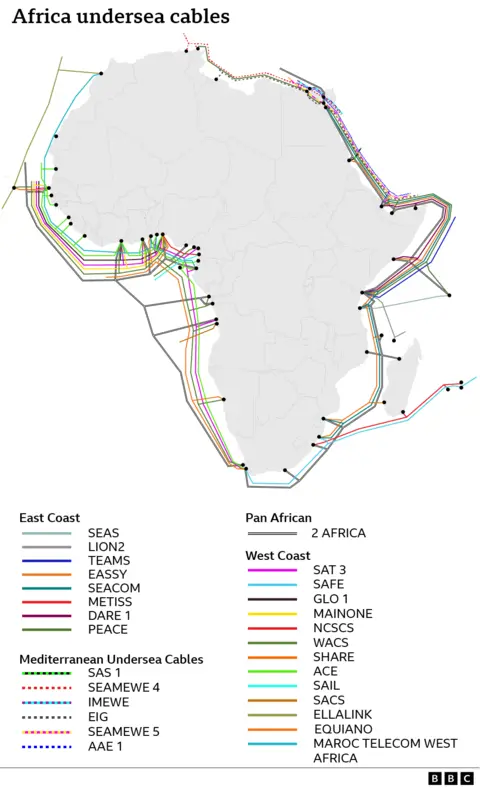

A cut to two of the undersea cables, which carry the data around the continent, early on Sunday morning, led to the recent disruption.

In March, damage to four cables off the West African coast caused similar problems.

And in February, the vital links were damaged in the Red Sea after the anchor of a stricken ship dragged through three cables.

Investigations are under way into this weekend’s case.

But it was also likely to have been caused by “an anchor drag” from a ship, Prenesh Padayachee, chief digital and operations officer at Seacom, which owns one of the two cables affected, told the BBC.

The second cable, known as Eassy, was affected at the same time and at the same place.

The incident happened off the South African coast, just north of the port city of Durban, according to the Communications Authority of Kenya (CAK).

The capacity of the infrastructure connecting Africa to the rest of the world has improved in recent years and telecoms companies are switching to other cables to maintain the service.

In Kenya, for example, the CAK said that local internet traffic was currently using The East Africa Marine System (Teams) cable that was not affected.

While Kenya has alternatives, other countries, such as Tanzania where connectivity levels hit 30% of what they were expected to be, do not.

The data should be able to find other routes, but when there is a limited number of pathways the service gets jammed and slows down.

AFP

AFPCases of cable damage are increasing but that is because the number of connections has also gone up.

“A lot of people don’t realise that the internet is held up by these cables that are like garden hosepipes except it’s one that stretches 10,000km, and that means that they are quite fragile,” Dr Jess Auerbach Jahajeeah, a researcher into digital connectivity at the University of Cape Town, told the BBC’s Focus on Africa programme.

Anchor dragging from ships close to shore is one of the most common causes of damage, but underwater rockfalls, as was believed to be the case in West Africa in March, and seismic activity can also affect the cables.

As “many of these subsea cables are often quite close to each other, then one activity on the ocean floor or one ship can damage multiple cables at the same time”, industry expert Ben Roberts said.

Repairing the damage, which requires specialised equipment and expertise, can take days or weeks, depending on the weather, sea conditions and the extent of the problem.

It took more than a month, for example, for the four severed West African internet cables to be repaired and returned to service.

“We are working on a temporary capacity solution to ensure connectivity is reinstated to the affected regions,” said Mr Padayachee from Seacom.

He added that they were “actively collaborating with various parties to expedite the repair process”.

Cable repair ship the Léon Thévenin, that had been docked in Cape Town, is being sent to the site of the damage and should be there in three days, said Chris Wood, who runs a company that has invested in Eassy.

AFP

AFPDespite an increase in connections, Africa’s reliance on a limited number of undersea cables for the internet makes the continent more susceptible to disruptions and exacerbates their impact.

Europe and North America, on the other hand, have a dense network of high-capacity overland and undersea cables that diversify connectivity routes and improve resilience.

While discussions have been ongoing to address Africa’s internet infrastructure challenges, progress has been slow because of logistical and financial constraints.

Dr Jahajeeah said one problem was that the support systems to repair the growing number of cables around the continent had not kept up with the growth.

While other ships can help out, the Léon Thévenin is the only repair ship dedicated to servicing Africa.

“The [ship] used to do two or three repairs a year [but] last year it did nine… and there is a real need for African governments and global governments to get together and say we need to ensure that there is no digital divide,” Dr Jahajeeah said.

Some people have proposed alternatives such as satellite internet links to bolster digital resilience.

Elon Musk’s Starlink project, for example, aims to provide high-speed internet to people who live in remote areas via a network of satellites. But is very expensive and currently not available everywhere.

The answer really lies in greater investment on the ground to support the vital communications infrastructure.

“It needs more networks, more connectivity, more data centres and more internet exchanges to make sure that we have a diverse connectivity,” said Mr Roberts.

Listen for more on fixing internet cables:

Getty Images/BBC

Getty Images/BBC