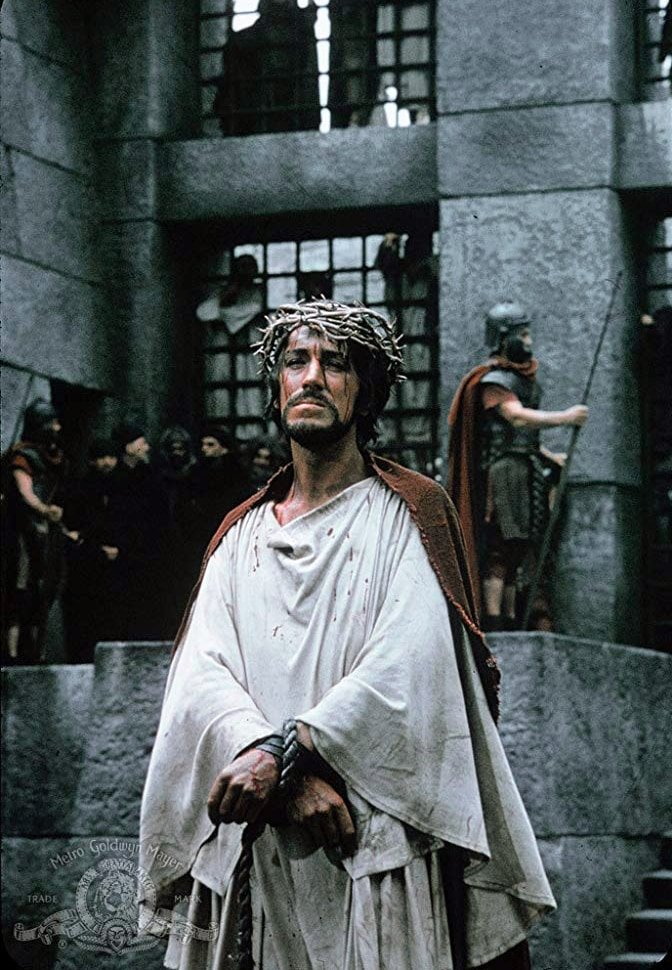

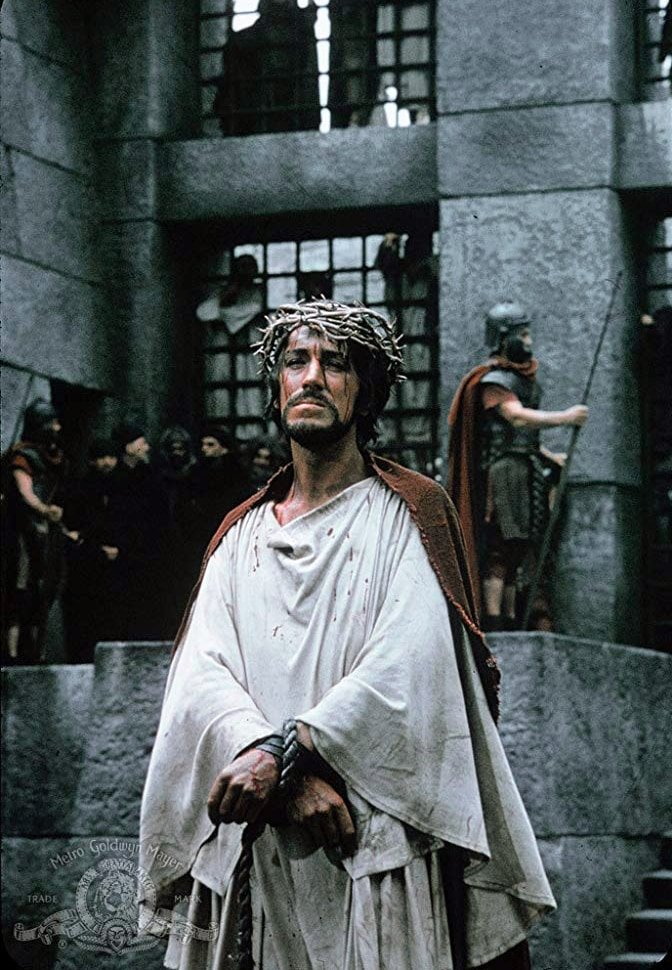

Max von Sydow as Jesus Christ in The Greatest Story Ever Told (1965)

One of the more unlikely sights in 1960s Hollywood cinema is John Wayne’s Centurion, in Roman toga and sandals, standing beneath the crucifix and declaiming in his rasping, frontier voice that “Truly, this man was the son of God!” The unfortunate Christ, nailed up above him, is Max von Sydow.

George Stevens’ The Greatest Story Ever Told (1965) is distinctly patchy even as biblical epics go, but largely thanks to his efforts as the Messiah, von Sydow (in his first non-Swedish part) became an international star. “Playing Jesus was in a way an impossible task,” he later recalled. “It didn’t tum out at all how I expected.”

Contrary to his screen persona as the saturnine and tormented Scandinavian, von Sydow has a droll sense of humour. In interviews he tells colourful anecdotes about being baptised by Charlton Heston (John the Baptist) in the Colorado River and being harassed by the small army of ultra-religious extras, who often seemed to confuse him with his role. “They did [the film] because it was supposed to be the definitive life of Jesus on film. They expected me to be very dedicated on every level, which of course I wasn’t. I was professionally dedicated but that was all.”

Christ wasn’t the first studio part von Sydow was offered. A few years earlier his agent had sounded him out about appearing in a James Bond movie. He passed on the opportunity, though he was later to play Blofeld in Sean Connery’s 1983 comeback film as 007, Never Say Never Again.

Never Say Never Again (1983)

And Christ and Blofeld provide the templates for von Sydow’s Hollywood career, with almost every other role a variation on one of these two prototypes. Either he plays visionaries, judges, priests and artists, or he’s the outsider/villain of choice, like Conrad Veidt and Peter Lorre a generation before. “Because I am not English or American, the parts I get are the foreigners,” he said in an interview with the Guardian. “And who is the foreigner? He is either the villain or the mad scientist or the sane scientist or the psychoanalyst or the artist. But always an outsider.”

One senses that von Sydow never took his US adventures too seriously. As a classically trained actor with a distinguished stage career behind him, he was secure enough in his reputation not to worry about playing stock types in studio movies. He must have known that his best and most challenging work was done back home in Europe.

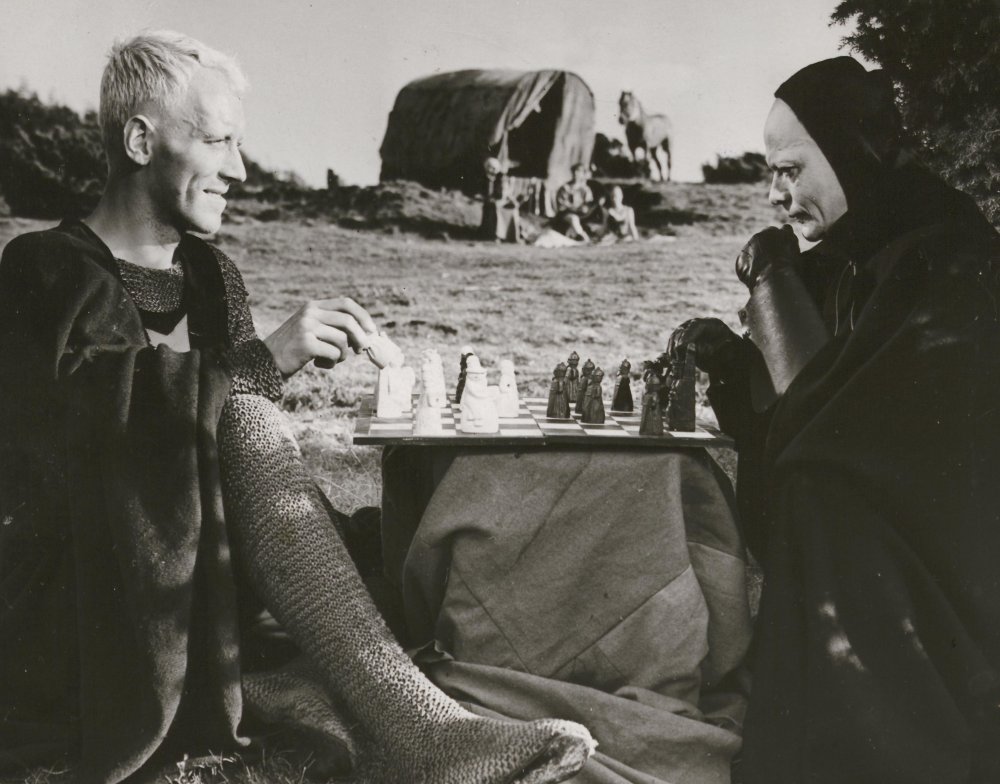

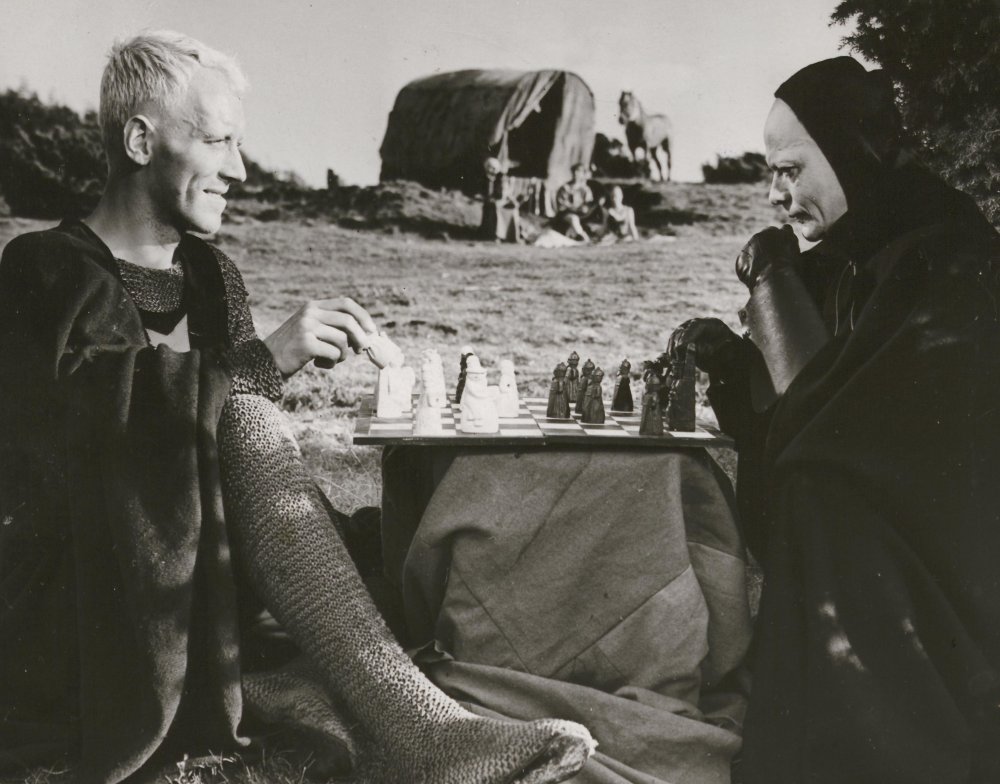

Von Sydow was 28 when his film career started in earnest with his role as the questing knight Antonius Blok, seeking knowledge and human contact in the face of death in Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal (1957). Blok is a study in anguish and self-loathing. “I see myself and am seized by disgust and fear,” he confesses early in the movie. “Through my indifference for people, I’ve been placed outside of their society. Now, I live in a ghost world, enclosed in my dreams and imaginings.”

The Seventh Seal began as a play, Wood Painting, written by Bergman for his students when he was a teacher at the drama school in Malmo. Its imagery was inspired by its director’s obsession with religious symbolism. Bergman, the son of a Lutheran pastor, was exploring religious faith and the fear of death, and many of Blok’s lines express the filmmaker’s own uncertainties. “Why does God hide in a cloud of half promises and unseen miracles… what will happen to us who want to believe but cannot?” are among the questions the knight asks.

Cast as a clown

The Seventh Seal (Det sjunde inseglet, 1957)

When Bergman decided to expand the play into a film he first offered von Sydow the role of a clown before finally agreeing to cast him as a knight. By then von Sydow was already established as a stage actor and had begun to work with Bergman at the Malmo Municipal Theatre. “We all knew that Max was one of the most talented actors of his generation. In private, he was rather shy and quiet, but on stage he had an absolute command of a part and of his audience,” Bergman later told film historian Peter Cowie.

The young actor’s background was very different to that of his director. Though he was brought up a Lutheran, he wasn’t especially religious. He was born in April 1929 in Lund in southern Sweden. His father William von Sydow was a professor of folklore at the Royal University of Lund and his mother was a former schoolteacher. It was expected that Max would pursue a career in academia or perhaps become a lawyer until his interest in performing was sparked when as a teenager he was taken to see a production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream at a new theatre in nearby Malmo.

After military service von Sydow enrolled in the Acting Academy at Stockholm’s Royal Dramatic Theatre. His first film role came in 1949 in Alf Sjoberg’s Only a Mother, a story focusing on deprived Swedish farm labourers that anticipated themes explored in one of his greatest roles, as the poor migrant farmer in Bille August’s Pelle the Conqueror almost 40 years later.

The Seventh Seal, the first of many films he has made with Bergman, was his real breakthrough, though in subsequent years he sometimes complained about how closely he was identified by audiences with Bergman: “They believe that’s the only thing I can do – be a Bergman actor. His films are rather serious, rather dark, and they think that’s the way I am too.”

Nonetheless, Bergman knew better than any other director how to draw subtle and intense performances from von Sydow. Much of the actor’s magnetism on screen derives from his brooding, angular physiognomy; he is a tall, lean, bony presence. Watch his work with Bergman and you’ll notice that his dialogue tends to be sparse – but he is shown in close-up after close-up. At times Bergman treats him almost as a silent-movie actor.

In The Seventh Seal he is seen first in full frame, slumped on his back on a rocky beach. He is staring upwards, but we are not sure at what. There is a chess board beside him. The sky is grey and the sea is lapping noisily.

As the ensuing close-up makes clear, he is exhausted. He cuts a forlorn figure, alone against the landscape, as insignificant as the tiny figure in Caspar David Friedrich’s Monk by the Sea. Heinrich von Kleist’s remarks about Friedrich’s painting apply equally to von Sydow’s knight: “Nothing could be more sombre nor more disquieting than to be placed thus in the world: the one sign of life in the immensity of the kingdom of death, the lonely centre of a lonely circle.”

Then, in a sequence often parodied, Death (Bengt Ekerot in a black cape) appears in front of the knight and challenges him to a game of chess. Though von Sydow’s Blok may be suffering torments about faith and mortality, he is also clearly a man of action. There is nothing spiritual about the way he barters with Death for some extra time. Nor is there anything ethereal about the firm kick he then gives his squire Jons (Gunnar Björnstrand) to raise him from his torpor. As they ride across the countryside they might even seem a Scandinavian version of Quixote and Panza were it not for the gravitas von Sydow shows. In the subsequent confession scene, shot in a shadowy cell with Death on the other side of the bars, Bergman cuts between von Sydow’s face and that of a grotesque wooden Christ, as if the two images were interchangeable. (And maybe this was where George Stevens had the idea of casting von Sydow as Jesus.)

Licence to fail

Amid all the apocalyptic talk of death and the plague there are lighter moments that show the actor to be capable of lyricism as well as gloom. When the knight meets Mia (Bibi Andersson), the juggler’s wife, we see him watching, smiling, as the couple play with their baby son and then share a simple meal of wild strawberries. He is asked about his sweetheart and begins to reminisce: “We were newlyweds, played together, laughed quite a lot. I wrote songs to her eyes, her nose, her exquisite small ears… In the evening we danced. The house was full of life.”

Von Sydow himself seems a little perplexed by The Seventh Seal, which he called “that strange film about death, religion and philosophy”. Nonetheless, the circumstances under which Bergman and his troupe made it were idyllic. As Peter Cowie says: “The actors at Malmo were under contract to the theatre for eight months of the year, and during the long summer vacation it became a tradition for them to join Bergman in making a film.” In other words, stage acting and screen acting went hand in hand, and on a project as experimental as The Seventh Seal there was licence to take risks and even to fail. This was in stark contrast to Hollywood, where, as von Sydow once put it, there is always a tendency to “judge the performance by the success or failure of the film.”

Despite his key role in The Seventh Seal von Sydow was given only minor parts in Bergman’s next two features Wild Strawberries (1957) and So Close to Life (1957). The former (at least for von Sydow) presents as stark a contrast to The Seventh Seal as can be imagined. He plays a cheery garage attendant and mechanic who comes skipping out when Professor Borg’s car pulls into town. Grinning inanely, he fills the car up with petrol while telling his wife Eva that Borg (Victor Sjostrom) is “the best doctor in the world”. As he checks the oil and water he refuses the doctor’s offer of payment. (“Certain things you remember. Things that can’t be paid for.”) It’s an inconsequential cameo but shows that von Sydow was capable of playing ‘bumpkins’ as well as tortured, introspective visionaries.

The Magician (Ansiktet, 1958)

One of his greatest performances came the following year, as the magician/mesmerist Albert Emanuel Vogler in The Magician (1958). “In most of his roles any sexual feelings are suggested rather than shown,” Cowie writes, pointing out that von Sydow rarely plays romantic leads. Vogler, however, is the actor at his most feline and unsettling: his very presence stirs up unholy erotic passions in the consul’s wife and his air of mystery and exoticism intimidates the police chief and the supercilious doctor who treat him so harshly.

Vogler pretends to be mute. He wears a long black wig, dyed eyebrows, a false beard, a black coat and a cravat – an outfit that makes him appear like a cross between Rasputin and Fu Manchu. Like the knight in The Seventh Seal, he is obsessed by death. As he and his colleagues drive through the woods, a coachman claims to have seen a ghost. Vogler investigates and is confronted with a mortally drunkard of an actor, who demands vodka. The drunkard can see at once that Vogler is in disguise. Vogler takes him aboard the coach, keen to witness the very moment of his death. “Look carefully sire, I will keep my eyes open for your curiosity,” the actor whispers as the life seeps out of him.

Bergman clearly identified with the magician and his troupe, who are both cherished and despised by the audiences for whom they perform. “The film is a metaphor for the artist and all the parts the audience projects into the artist,” von Sydow has said. “It is – or rather was – Bergman’s own situation, for the audience projected all their fantasies on to him, and he became an extremely interesting and fascinating individual.”

Vogler is an expert in the “science of animal magnetism”. Bergman shows us constant close-ups of the mesmerist staring forlornly ahead as the authorities taunt him. Though he doesn’t speak in public, he is never a neutral presence and we are always aware of his antagonism towards his petty bourgeois tormentors. In one key scene, after he has again been taunted by the doctors, he pulls off his disguise, lies beside his wife and at last gives vent to his feelings. “I hate their voices, their bodies, their movements, their voices,” he hisses.

Anger comes naturally to von Sydow. Witness his rage and despair in the closing scenes of Bergman’s Virgin Spring (1960), when he has just massacred the herders who raped and killed his daughter. Rather than catharsis, the slaughter brings him only torment. He prays, but his prayer is a rant in which he rails against the God who allowed these deaths to happen and did nothing.

The outsider

If von Sydow has the physical presence to play the tragic hero on screen, he is also adept in supporting roles. In Bergman’s Through a Glass Darkly (1961) he was the fussy husband to Harriet Andersson’s schizophrenic.

Winter Light (Nattvardsgästerna, 1963)

As Jonas Persson in Bergman’s Winter Light (1962) he is first seen in the church, a gaunt, anonymous figure in a drab mackintosh. Unlike the knight or the magician, Jonas is not a character in a heroic mould. He is a suicidal depressive with too much of an inferiority complex to look anybody in the eye. As his mousy wife (Gunnel Lindblom) tells the parson (Gunnar Björnstrand) as Jonas sits with his hand buried in his chin, he is “at his wit’s end”. He has been driven to the brink of despair by newspaper stories about China. “The article said that the Chinese were brought up to hate and it’s only a matter of time before the Chinese has atom bombs,” the wife explains. Shy, sensitive Jonas can’t cope with his feelings of dread, and nothing the parson says can soothe him.

Jonas is precisely the type of role von Sydow wouldn’t have been offered in Hollywood, where he was condemned always to play exotic outsiders. It’s telling that he frequently cites his role as Lasse, the poor Swedish farmer in Bille August’s Oscar-winner Pelle the Conqueror (1987), as among his favourites. He gives an immensely moving and dignified performance as the man who takes his son to Denmark in search of a better life but encounters only hardship and humiliation. “If I had my choice, I know I could do ordinary people much more than I have been allowed to – workers, farmers, fathers… just a regular person with regular, everyday problems,” he said in an interview in the early 1980s.

It was hardly a surprise that US casting directors were so reluctant to use von Sydow as an average Joe. He had a gravitas about him that made him a natural choice for the priest/archaeologist Father Merrin in The Exorcist (1973).

In theory von Sydow, then in his early forties, was too young for a role as an old man with a heart problem, but he invests the character with dignity, pathos and even a little humour. “My doctors tell me not to, but thank God my will is weak,” he tells Ellen Burstyn when she offers him some alcohol to put in his coffee. In this scene (included in the restored version of William Friedkin’s film) he is waiting downstairs for his battle with the devil to begin. The iconic image of him with his back to camera, standing in the streetlight as he arrives in Georgetown on a wet, misty night, is almost as familiar as the knight playing chess with Death.

In truth, few of von Sydow’s Hollywood films are especially memorable. He was a Nazi officer in Escape to Victory (1981), an assassin in Three Days of the Condor (1975), a captain of a luxury liner in Voyage of the Damned (1976). He tackled all these roles with his customary discipline and professionalism but there was little sense that he was being stretched.

At times he was reduced to self-parody. Take, for instance, his good-humoured turn as Barbara Hershey’s absurdly self-important artist boyfriend Frederick in Woody Allen’s Hannah and Her Sisters (1986). (”I’m going through a period of my life where I can’t be around people” is what passes for small talk in his universe.)

The real challenges lay back in Europe. In 1988 he made his debut as a director with Katinka, an adaptation of a Herman Bang story. He was proud of his performance as the venerable Norwegian novelist Knut Hamsun, who disgraced himself by encouraging young Norwegians to welcome the Nazis with open arms, in Jan Troell’s Hamsun (1996).

Interviewed at the time of Scott Hicks’ Snow Falling on Cedars (1999), in which he gave a grandstanding performance as an elderly judge, von Sydow lamented that he was “growing away from the good parts”. Of course, that wasn’t the case: for most of his career von Sydow had been playing characters far older than he really was. That sonorous, doom-laden voice (heard to fine effect narrating Lars von Trier’s 1991 Europa) remains intact and his features are as jagged as ever.

For filmmakers who want to invoke a golden age of European arthouse cinema or to find someone to play venerable Prospera types, von Sydow is as much in demand now as when he took his first move in that fateful game of chess almost so years ago.