Credit: Michelle Thompson

For more than 20 years, it has been hard to imagine world cinema without a strong Brazilian presence. Walter Salles’s Central Station (1998), Fernando Meirelles’s City of God (2002), Héctor Babenco’s Carandiru (2003), José Padilha’s documentary Bus 174 (2002) and his 2007 Berlin winner Elite Squad, and Kleber Mendonça Filho’s Neighbouring Sounds (2012) – these are just some of the high-profile titles that have given Brazil a place of honour on cinema’s map since the ‘retomada’, the resurgence in national film production in the mid-1990s, following a shutdown at the end of the previous decade.

Bacurau is released in UK cinemas on 13 March and on Mubi on 27 March.

The Invisible Life of Eurídice Gusmão will be released in the UK in April.

This year in particular has been triumphant for Brazil. In Cannes, Bacurau – a collaboration between Juliano Dornelles and Mendonça Filho – won the Jury Prize, while Karim Aïnouz’s The Invisible Life of Eurídice Gusmão won the Un Certain Regard award. Favela drama Pacified – a Brazilian production by US director Paxton Winters, with Darren Aronofsky among its producers – won top prize in San Sebastián, and Maya Da-Rin’s debut The Fever, whose hero is a member of the indigenous Desana people, triumphed in Locarno. Other breakthrough titles of 2019 include Alice Furtado’s debut Sick, Sick, Sick, about a teenager turning to witchcraft; and Divine Love by Neon Bull director Gabriel Mascaro, a visually dazzling evocation of a future Brazil gripped by an evangelical sex cult.

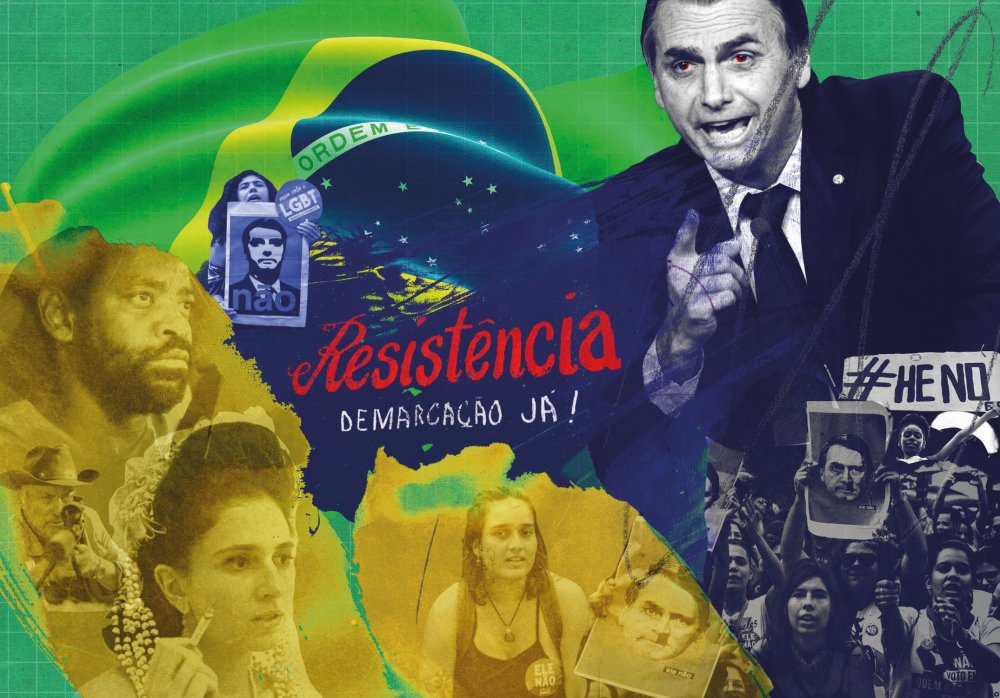

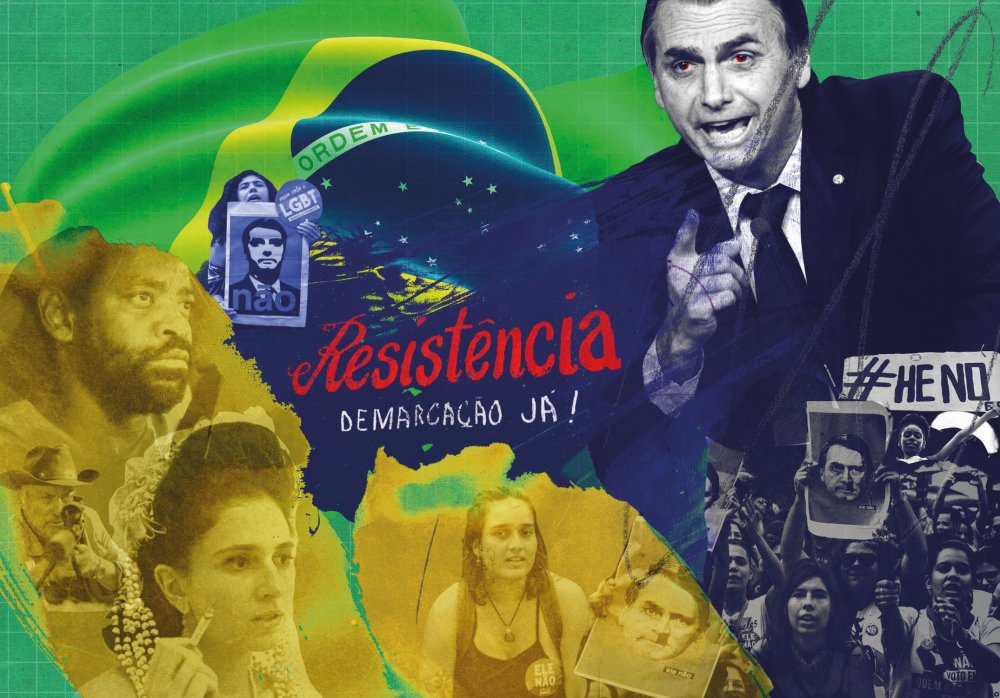

Sick, Sick, Sick (Sem seu sangue, 2019)

Yes, 2019 was an annus mirabilis for Brazilian cinema – but it has also been a year of nightmares, with fears of worse to come. On 1 January, extreme-right politician Jair Bolsonaro assumed his duties as president. One key aspect of his policy – a virulent contempt for the preservation of the Amazon rainforest and its peoples – bodes very ill for the planet as a whole. But Bolsonaro has also launched a concerted assault on culture, including the national film industry and public funding for cinema. He wants a national cinema that promotes family values and a hyper-conservative agenda, and intends to make it happen through the introduction of ‘content filters’, which will exclude what he sees as the wrong sort of cinema – a move that, Padilha has commented, represents “a return to censorship for Brazilian cinema”.

One of the new regime’s first moves was to dissolve Brazil’s Ministry of Culture and replace it with a ‘Citizenship Ministry’, which also includes sport. In March, key funding was pulled for Cinema do Brasil, which promotes co-production and supports Brazilian films’ presence at international festivals.

Burning Night (2019)

And there has been a concerted attack on national film agency Ancine, responsible for the administration of some $91.5 million annually, with Bolsonaro threatening to close it if it doesn’t comply with his demands; indeed, in August, he fired its president, Christian de Castro. Bolsonaro proposes to relocate Ancine from its current headquarters in Rio de Janeiro to the capital Brasilia – a move designed to tighten control on film production, and one that has alarmed filmmakers, who see themselves distanced from the funding channels that have allowed them to flourish. “Brasilia is completely isolated from the people – it’s like a fortified castle,” says Eryk Rocha, director of the feature Burning Night, which recently screened at the BFI London Film Festival.

Another move, in October, was Bolsonaro’s appointment of a new chief of economic development at Ancine – Edilásio Barra, a TV presenter and evangelical pastor – which is very much in line with a reactionary moralising drive. Bolsonaro is particularly opposed to sexual content, and has denounced as pornography the 2011 box-office hit Bruna surfistinha (currently on Netflix as Confessions of a Brazilian Call Girl): in fact, the film is a cheerfully ribald but altogether mainstream adaptation of the memoirs of a sex worker turned online personality.

Bruna Surfistinha (Confessions of a Brazilian Call Girl, 2019)

Particularly in the president’s firing line is LGBT+ content. In August, Ancine cancelled some $17 million in funding to 80-odd films, four with LGBT+ themes – although this move was subsequently overruled by a federal court in Rio – and culture secretary Henrique Medeiros Pires resigned over the president’s anti-LGBT+ policy. The Supreme Court also, incidentally, quashed a move by Rio’s mayor Marcelo Crivella, an evangelical bishop, to ban an Avengers comic showing two men kissing.

Bolsonaro has said that Brazil should be producing films about national heroes. One title of 2019 fits that description to a tee, but not quite in the way he had in mind. Directed by Elite Squad/Narcos star Wagner Moura and premiered at the Berlin Film Festival, Marighella is a punchy thriller-style portrait of Carlos Marighella (played by singer and actor Seu Jorge), a left-wing militant who fought, and was killed by, Brazil’s military dictatorship in the 1960s.

Marighella (2019)

Marighella was due for release in Brazil on 20 November – marking the 50th anniversary of its subject’s death – but this was cancelled, reportedly because its producers were unable to “comply with procedures” required by Ancine, placing the film’s domestic future in question. Karim Aïnouz sees such anomalies as part of a stealth approach: “It’s what they call a ‘turtle operation’ – they found a hole in the bureaucratic process. It is censorship, obviously, but in a way that you can’t put your finger on.”

Meanwhile, says Tatiana Leite – whose films as producer include 2018 Sundance-premiered Loveling – private bodies such as banks and other corporations that used to provide finance are now shying away for fear of government reprisals. In April, oil company Petrobras cancelled its funding for Brazilian productions and festivals, while Banco do Brasil bowed to government pressure to pull a commercial promoting diversity, featuring black and transgender actors. Leite herself recently applied for funding from a bank: “They wanted to know, ‘Is there any political or gender content?’ The banks are working as censors – they don’t want to do anything that provokes any reaction from the government.”

Current Brazilian cinema, at its most energetic and committed, focuses on topics that are anathema to the ruling regime. Maya Da-Rin’s The Fever was hailed online by Laura Davis for Sight & Sound as “a searing indictment of her country’s leadership and fascism worldwide”. Bacurau depicts a rural community in the northeastern province of Pernambuco fighting for survival against corrupt politicians and ‘murder tourists’ who hunt locals for pleasure.

The Fever (A Febre, 2019)

Rocha’s Burning Night, shot in a poetic quasi-documentary style, features a black working-class hero, a cab driver facing everyday struggles but also finding love in Rio’s streets at night. Then there’s Seven Years in May from Affonso Uchôa (co-director of 2017’s superb Araby), a stylised 42-minute piece in which a young man narrates his real-life experience of police corruption and brutality.

Seven Years in May (2019)

Aïnouz’s work has often focused on LGBT+ themes – notably Madame Satã (2002), about a black drag artist. His award-winning The Invisible Life of Eurídice Gusmão is a melodrama about two sisters whose lives are sabotaged by a tyrannical father. After he started the project, says Aïnouz, “it took on an urgency I didn’t think it had in the beginning. What’s happening with the election of Bolsanaro is really related to a failure of patriarchy – the men are desperate to not let go of power.”

The Invisible Life of Eurídice Gusmāo (2019)

Some members of Brazil’s National Congress have come together to find ways of supporting national cinema, and the arts world in general has mobilised, with the musical legend Caetano Veloso one of the leading figures putting the cultural argument to Congress. But a definite anxiety is gripping the film community, which is suddenly facing unprecedented difficulties in securing finance. Bacurau co-director Dornelles says: “Me and Kleber [Mendonça Filho] are in a different situation from many filmmakers, because of the response to our film. But many of our friends are considering not working in cinema any more because there’s no hope for the next years.”

Bacurau (2019)

Even with the international success of Bacurau, his co-director is worried. “I’m 50,” says Mendonça Filho. “I don’t want to go back to guerrilla filmmaking.” But he does see hope for people prepared to take that low-budget route: “Digital technology is what makes me feel optimistic – and the great young people we’ve been meeting.”

He is also sanguine about regional movements in Brazil, which has benefited in recent years from decentralised funding; he mentions the south-eastern state of Minas Gerais (Affonso Uchôa’s home territory) and Pernambuco in the north-east (the settings of his own films) as having particularly rich cinemas and still, he feels, healthy prospects.

Rocha, too, sees hope in the conviction of a young generation. His father was the revered innovator Glauber Rocha, one of the key names in Cinema Novo, Brazil’s radical film movement of the 60s. Rocha can see a new generation of filmmakers working in collectives in a similar way to resist Bolsonaro’s oppressive order. “Maybe we’ll have to incorporate this energy, this war footing that Brazilian people have been living with on a daily basis – and the survival instinct to invent a new territory.”