Portrait of Robert Brown.

| Photo Credit: WELLCOME LIBRARY, LONDON / Wikimedia Commons

Even a little over 200 years ago, the world was very unlike what we are used to everyday now. Instant communication was inconceivable. Getting from one place to another was often a slow, laborious process. And vast spaces were still uncharted.

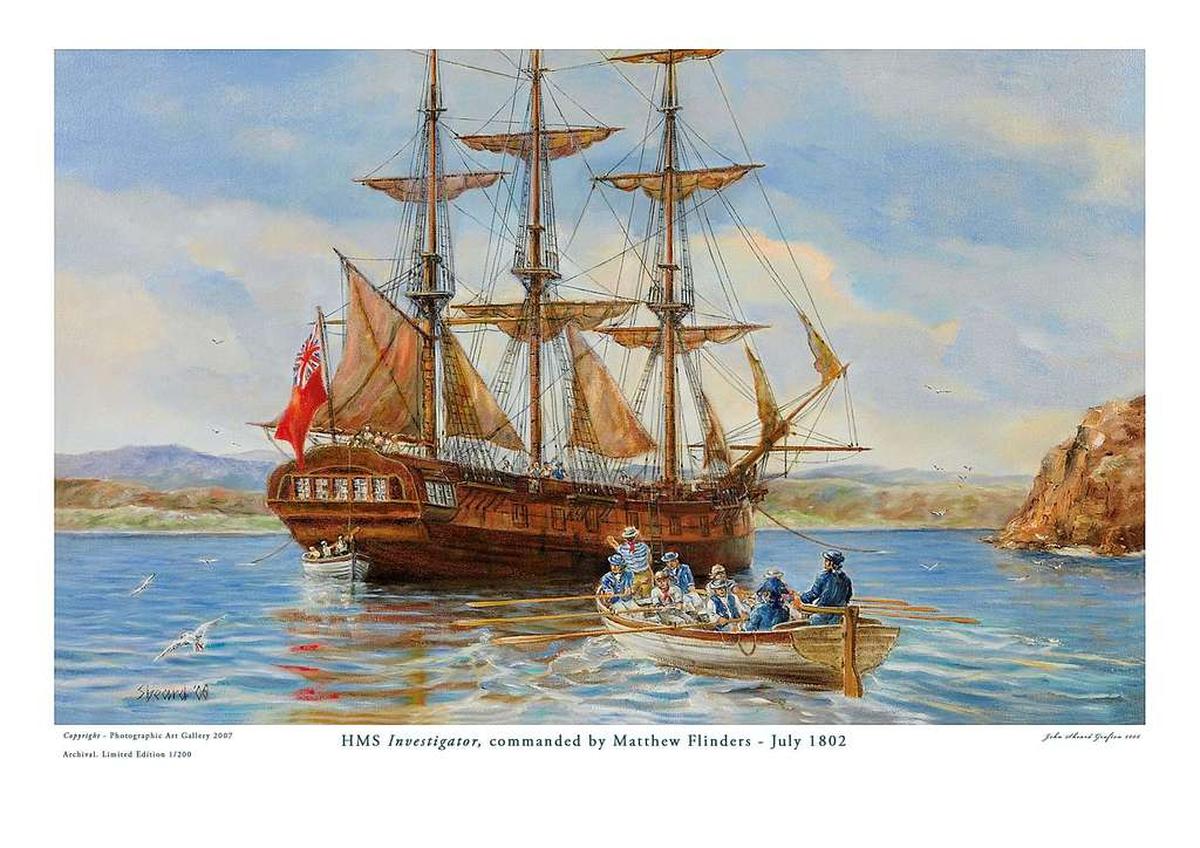

Australia was one such landmass, really! The HMS Investigator was a British vessel used for an expedition from 1801-1803 to map the Australian coastline. Part of this expedition was Robert Brown, a botanist who went on to contribute immensely through his original work on the flora of Australia.

Drawn to botany

Brown, however, didn’t always want to take to botany. Born in 1773 in the coastal town on Montrose in Scotland, Brown’s family moved to Edinburgh in 1790. Despite initially planning to study medicine at the University of Edinburgh, Brown found himself drawn to botany. He travelled into the Scottish Highlands, collecting plants and writing their descriptions with meticulous detail, and even discovered a new species of grass, Alopecurus alpinus.

Even when his studies were interrupted by military service, being stationed in Ireland as a surgeon’s mate afforded him plenty of time to tend to his interests. So much so that by the turn of the century, he established himself as an amateur botanist in the Irish community, without a formal degree.

HMS Investigator’s naturalist

Brown’s hopes of earning a living as a full-time botanist received a boost when he was selected as the naturalist for a scientific expedition aboard the Investigator, and the British Navy appointed Lieutenant Matthew Flinders as its commander. The voyage was planned to explore “New Holland” – the continent that we now call Australia.

An illustration of the HMS Investigator.

| Photo Credit:

Wikimedia Commons

Tasked with collecting as many plants, insects, and bird species as possible, Brown set sail from London aboard the Investigator in July 1801. Months later, they stopped at the Cape of Good Hope for a couple of weeks, during which Brown experienced “some of the pleasantest botanizing,” in his own words.

Having arrived in Western Australia by December, Brown spent the next year and a half collecting over 3,000 specimens, many of which were previously unknown and local to Australia. With the circumnavigation of Australia completed and the mapping of Australian coastline achieved, the voyage came to an end on June 9, 1803 when the Investigator reached Port Jackson.

Classifies plant species

Even though many specimens were lost during his return to England, Brown devoted considerable time after getting home in 1805 classifying the specimens that he had carried with him. With the expedition effectively launching his career as a botanist, Brown went about publishing some of his results from this trip in a 1810 book titled Prodromus Florae Novae Hollandiae et Insulae Van Diemen. Now considered his major work and a classic in systematic botany that laid the foundations for Australian botany, Brown published only one volume as it didn’t quite fly off the shelves.

As interested in studying the physiology of plants as he was in collecting and classifying them, Brown was captivated by the pollen particles of a certain plant species floating in water under his microscope. He observed that there were smaller particles jiggling in what seemed like random motions within the grains of pollen.

Repeats his experiment

While Brown wasn’t the first to observe such motion in small particles, he went on to repeat his experiment with other plants, powdered pit coal, dust, glass, and metals, with similar results. Despite the fact that Brown died in 1858 without providing any theory to back his observations, this random jittery behaviour is referred to as Brownian motion.

The task of explaining its mechanics was taken upon by celebrated theoretical-physicist Albert Einstein. In addition to reasoning that atoms or molecules of a liquid would bombard particles and make them move randomly when tiny, visible particles were suspended in a liquid, he also explained it further in a 1908 paper. He even gave a formula based on the distance the particle travels, which was later tested experimentally and verified.

In addition to Brownian motion, a number of plant species are also named in Brown’s honour. Brown’s banksia (Banksia brownii) and Brown’s box (Eucalyptus brownii) are two such species. Both of these, unsurprisingly, are found in Australia.