German archaeologists discovered that the skulls of three medieval Viking women found on the Swedish island of Gotland in the Baltic Sea showed evidence of an unusual procedure to elongate their skulls. The process gave them an unusual and distinctive appearance, according to a paper published in the journal Current Swedish Archaeology. Along with evidence that the Viking men from the island may have deliberately filed their teeth, the discovery sheds light on the role body modification may have played in Viking culture

When people hear about Viking body modification, they probably think of Viking tattoos, particularly since the History Channel series Vikings popularized that notion. But whether actual Vikings sported tattoos is a matter of considerable debate. There is no mention of tattoos in the few Norse sagas and poetry that have survived, although other unusual physical characteristics are often mentioned, such as scars.

The only real evidence comes from a 10th century travel account by an Arab traveler and trader named Ahmad Ibn Fadlan, whose travel account, Mission to the Volga, describes the Swedish Viking traders (“Rusiyyah”) he met in the Middle Volga region of Russia. “They are dark from the tips of their toes right up to their necks—trees, pictures, and the like,” Ibn Fadlan wrote. But the precise Arabic translation is unclear, and there is no hard archaeological evidence, since human skin typically doesn’t preserve for centuries after a Viking burial.

But there is evidence of body modification. Archaeologists in the 1980s noted “strange marks” on the teeth of male Viking Age skulls that looked like the teeth had been deliberately filed. Some 130 examples of Norse skulls with filed teeth have since been found, 80 percent from Gotland. The marks are usually on the upper front teeth and feature horizontal grooves in straight-line patterns, though there are also the occasional crescent-shaped marks as well. A 2005 study by osteologist Caroline Arcini of Sweden’s National Historical Museums—who later wrote a book with an overview of the many cases she found of filed teeth among Norsemen, among other topics—concluded that the marks were “skillfully made” and that it was unlikely that the men in question had filed their own teeth and made the marks themselves.

There are other cultures known to have practiced tooth modification, but it was not typical of medieval Europe, and the Vikings did not usually have dental work done. The procedure would have been very painful, but Arcini found no evidence that the practice was part of an initiation or rite of passage for young men, nor was it likely such men were warriors, elite members of society, or slaves. Given the concentration of such men from Gotland, she suggested the custom originated on the island or that the teeth were filed elsewhere, but somehow the island was a gathering point for such men.

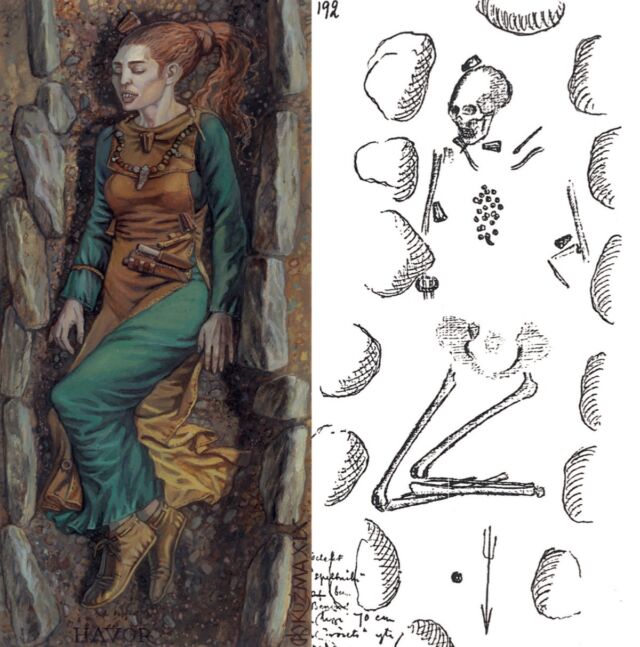

Matthias Toplak (Viking Museum Haithabu) and Lukas Kerk (University of Munster), co-authors of this latest study, suggest that the teeth filing may have been a way to identify fellow members of a closed group of merchants. The three 11th century women with elongated skulls offer a more puzzling conundrum. The skulls were excavated from three different cemeteries on Gotland, buried sometime in the second half of the 11th century, fully dressed with ornate jewelry but little else in the way of grave goods. Two were between the ages of 25 and 30, while the third was an older woman between 55 and 60.

Mirosław Kuźma/Matthias Toplak

Given that all three burials are relatively close chronologically, the authors concluded the three women likely shared a common background that involved the practice of skull modification. But there are scant clues as to why such modifications were performed. Per Toplak and Kerk, there is evidence of skull elongation being practiced in various ancient and medieval cultures, from South America and Central Asia to Southeast Europe. The process typically involved binding the heads of young children (usually female) under the age of 3 with wood or cloth.

It’s possible the practice eventually found its way to Gotland via Bulgaria during this period, although another alternative is that the three women were actually born elsewhere and eventually settled on Gotland—perhaps the children of traders. That might explain why the island has no infant or child burials showing signs of elongated skulls, suggesting it was a foreign practice not widely adopted in Viking Age Gotland.

It was likely performed on the three women during early childhood “to express their affiliation to a certain social group,” Toplak and Kerk wrote. “On Gotland, however, this sign was probably unknown to the wider society. The body modification may have been perceived as an exotic or foreign trait which did not prevent the individual from being integrated into the community and its prevailing burial customs.”

Current Swedish Archaeology, 2024. DOI: 10.37718/CSA.2023.09 (About DOIs).