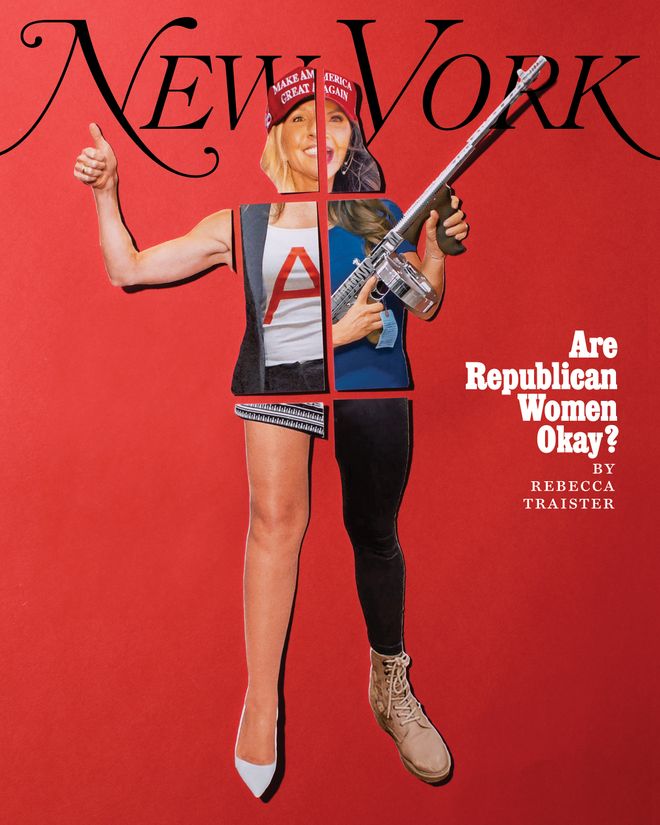

From left, Barbara Bush, Kay Bailey Hutchison, Elizabeth Dole, Kristi Noem, Nancy Mace, and Valentina Gomez.

Photo: Porter Gifford/Liaison (Dole); Ron Sachs/Consolidated News Picture (Bush); Joe Raedle/Getty Images (Hutchison); Jeff Dean/AP Photo (Noem); Evelyn Hockstein/Reuters (Mace)

Can you provide a definition for the word woman?”

Tennessee senator Marsha Blackburn lobbed this query at Ketanji Brown Jackson during her 2022 Supreme Court confirmation hearings. Blackburn was doing her bit for her party’s effort to enforce transphobic gender conformity, positioning herself as a defender of womanhood as something fixed and narrow. When Jackson declined to provide Blackburn with a definition, noting that she was not a biologist, the senator took the opportunity to dial it up a notch. “The fact that you can’t give me a straight answer about something as fundamental as what a woman is underscores the dangers of the kind of progressive education that we are hearing about,” Blackburn said with lip-smacking satisfaction.

Two years later, Republicans remain cruelly closed to the realities of gender fluidity and trans existence. But how the party understands — and represents — womanhood more broadly? Well … that’s getting weird. As we cruise toward November with two ancient white men on the presidential ticket and the rights of millions of people who are not white men in the balance, the public performance of Republican womanhood has become fractured, frenzied, and far less coherent than ever.

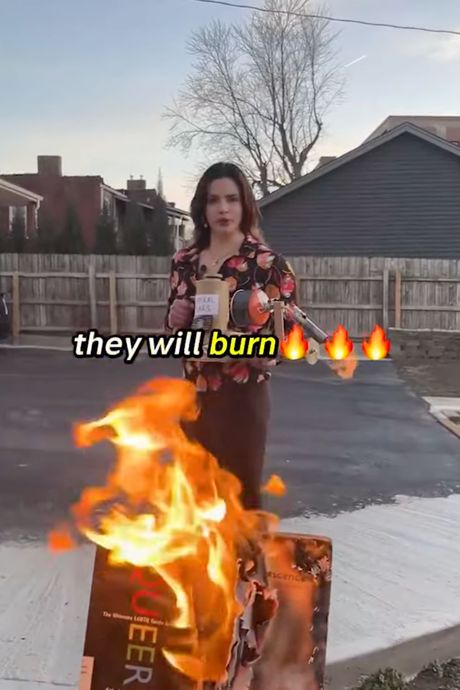

“A true conservative woman,” Valentina Gomez, one of several Republican candidates vying to be Missouri’s next secretary of state, told me in an email this spring, “speaks the truth, works hard, loves and knows how to use guns of multiple calibers, cares for the wellbeing of children and her family, doesn’t sleep with multiple men and most important, does not murder babies.”

The 25-year-old Gomez made a viral ad in February in which she took a flamethrower to a pile of sex-education and LGBTQ+ books from the public library. In May, she filmed herself running through St. Louis wearing a weighted vest and advising, “Don’t be weak and gay; stay fucking hard.” The day before, she had embraced her softer side, posting a photo of herself on X in a pale-pink pantsuit and pumps, with a winning smile and her eyes cast heavenward, under a caption restating Blackburn’s question: “What is a woman?”

Gomez told me feminists “have made men the enemy,” adding, “they end up alone with three dogs at the age of 50 with no kids or husband” — a time-honored Republican sentiment that liberal women, unlike conservatives, are sexless, unmarriageable spinsters. But even that rusty rhetorical frame is wobbly: In April, 31-year-old far-right activist Laura Loomer, standing outside Donald Trump’s criminal trial in New York, told the New York Times, “You think I have a dating life? You think I’m married? You think I have kids? Do you think I go out and do fun things? No. Because I’m always putting every extra bit of time that I have into supporting President Trump.” Loomer told the paper she would not be at the courthouse the next week because she had to return home to Florida to take care of her dogs.

Contradictions abound among conservative women in Washington. In response to Jackson’s testimony, Georgia representative Marjorie Taylor Greene attempted to be authoritative on the matter. “I’m going to tell you right now what is a woman,” she said. “We came from Adam’s rib. God created us with his hands. We may be the weaker sex — we are the weaker sex — but we are our partner’s, our husband’s, wife.” But Greene, who has since divorced, regularly refers to men, including Speaker Mike Johnson and President Biden, as “weak” and is not shy about showing off her own brawn. In May, in the wake of a dustup with Democratic Texas representative Jasmine Crockett in which the two traded barbs about each other’s appearance, Greene posted a video of herself lifting heavy weights to a song by Sia: “I’m unstoppable / I’m a Porsche with no brakes / I’m invincible / Yeah, I win every single game.”

“Under the surface, subcutaneously, there is a tug-of-war,” said Nancy Mace, a 46-year-old second-term Republican congresswoman from South Carolina. Mace was reflecting on the tension between presenting as traditionally feminine and deploying emasculating language that can make her sound more like Andrew Tate and his overheated manosphere buddies than Republican foremothers such as Margaret Chase Smith or even Michele Bachmann. Mace regularly declares that her male enemies, including former House Speaker Kevin McCarthy, with whom she has a bitter rivalry, and Hunter Biden, the president’s son, have “no balls.”

“There are the traditional roles of women in society, some biological. We’re meant to nurture; we’re meant to breastfeed our kids,” Mace told me over Zoom. “But my mom worked. I’ve worked my entire life since I was 15. It’s a balance between what’s your feminine side and your Main Character Energy.” Mace was explicit: “I do have Main Character Energy. I am an alpha dog, and so is my little six-pound dog, Libby.”

The Republican women seeking to steer their party into the future are finding themselves in a series of constrictive binds: between upholding a conservative white patriarchy that has outlawed abortion and asserting their value as women; between projecting traditional notions of compliant, cheerful femininity and channeling the testosterone-driven rage of the conservative infotainment complex; and, above all, between trying to build independent political identities and slavishly following Donald Trump. That devotion has come at the cost of alienating suburban white women, who have been crucial to Republicans for decades but, since 2016, have been peeling away in response to Trump’s pussy-grabbing malevolence and his party’s ruthless campaign against reproductive rights.

It’s surely a nasty tangle for them, but for those of us watching at home, Republican women’s efforts to bridge these impossible chasms have a stupefying quality: What to make of these women?

As the Alabama political columnist Kyle Whitmire wrote after Katie Britt, his state’s U.S. senator, delivered the response to Joe Biden’s State of the Union address from her kitchen in a demonic whisper, “Katie Britt glitched out on national television and left millions of Americans asking what the heck they just watched.” Weeks later, South Dakota governor Kristi Noem’s strenuous efforts to show off her casually cruel streak to Trump derailed her own vice-presidential audition when it emerged that her book contained a story about how she once shot her puppy and left the body to rot in a gravel pit.

Then there are the duck-lipped, smoky-eyed stylings of Donald Trump Jr.’s fiancée, Kimberly Guilfoyle, who danced to “Gloria” shortly before insurrectionists tore through the Capitol on January 6, 2021, and this spring announced a children’s book called The Princess & Her Pup. The former president’s daughter-in-law, RNC co-chair Lara Trump, recently promised “four years of scorched earth when Donald Trump retakes the White House” and posted a video of herself in sequined pants and stilettos as she played “Let It Be” on piano. The gun-toting congresswoman Lauren Boebert has railed against “teaching kids how to have and enjoy sex, even same-sex sex, how to pleasure themselves,” yet last fall was ejected from a theater for lewd behavior that included grabbing her date’s crotch during the performance. Mace made headlines in 2023 for joking about her sex life to a roomful of Christian conservatives at a prayer breakfast.

Some of this is surely just old-fashioned political hypocrisy, particularly unpleasant coming from a right that has for generations sought to police all sorts of things that it itself engages in: Do as I legislate, not as I do. But in a post-Dobbs political climate in which Republicans have grown only more aggressive on issues of gender identity, contraception, and sex education, the ways in which the party’s women have been comporting themselves loom large.

On the cusp of an election season that could further reshape this democracy and women’s place within it, the questions facing the women of the American right are tricky. Are they supposed to be cutthroat or cute? Cold enough to kill a dog or warm enough to bake an apple pie? To whom is their devotion chiefly addressed: country, husband, God, or Trump? And how might their womanhood complicate their responses to the closing of obstetrics wards or the fact that their party’s leader was convicted of falsifying business records to cover up an extramarital affair with an adult-film actress?

The challenge of navigating these thorny questions has left many of them caroming from high-pitched rancor, to contorted eroticism, to the seemingly snug comforts of trad-wife chic. The spectacle can provoke amusement, fury, and a frisson of horror-movie unease. For if the women of today’s Republican Party are upending gender conventions in unprecedented fashion, they’re doing it in service of a party that has never been more openly hostile to women and their rights.

Lauren Boebert with Trump in a “LET’S GO BRANDON” dress.

Photo: Lauren Boebert/X

In both parties, women have never had it easy; this is a business that remains, 235 years in, overwhelmingly run by men. And for a time, it was Democratic women who encountered the gnarlier complexities.

As members of the party that at least theoretically represented the gains of the women’s movement that were so disruptive to the old gendered order, they could not themselves present as too aggressive for fear of being seen as radical, nor could they be too vulnerable, feminine, or even conventionally beautiful lest they be dismissed as unserious. Jennifer Granholm, a former pageant contestant and the first woman to govern Michigan, has described cutting her hair short and trying to add gray streaks when she ran her first campaign in 1998. “You had to look completely asexual,” she once said. “The first thing they think about is how you are shaped, what you are wearing. You have to be as neutral as possible so that people will pay attention to the words coming out of your mouth.”

Meeting ridiculous gendered expectations could mean ridiculous micro-humiliations: When Hillary Clinton told reporters in 1992 that she had chosen to pursue a paid profession rather than stay home to bake cookies, she was pressured to participate in a “First-Lady Bake-Off” to prove her wifely chops. Fifteen years later, during her first presidential run, the presence of a body that was not male was such an anomaly on the campaign trail that the Washington Post published a fashion feature about how she was choosing to handle her cleavage. Clinton was perhaps the most acute example of an assertive Democratic woman whose efforts to satisfy a ravening press and public intolerant of female complexity left her so twisted and poll-tested that she became largely illegible as human, let alone female.

Meanwhile, Republican women faced limitations of their own but for a long time appeared at ease with them. Many came off as maternal and content, conservatively coiffed and shoulder-padded, a comfortable match for a party that wanted to offer reassurance to a nation jittery about women’s liberation. Think Elizabeth Dole, a Reagan Cabinet member, future senator, and presidential candidate whose chatty, Oprah-style stroll through the crowd on the night of her husband’s 1996 presidential nomination was the (sole) highlight of that convention. But they could also be tough and mean — Barbara Bush once called Geraldine Ferraro a bitch!

The Republican Party, through the 1990s and into the new millennium, included quite a few “moderate” women, such as Kay Bailey Hutchison of Texas and Olympia Snowe and Susan Collins of Maine, who believed in fiscal conservatism but also held positions on so-called social issues that were comparatively liberal. They were, like many in their party before its sharp anti-abortion turn, “pro-choice.” They worked with Democrats to reach compromises, and the women on both sides of the aisle appeared to be friendly with one another: Collins partnered with Kirsten Gillibrand on the repeal of “don’t ask, don’t tell,” and Gillibrand helped then-Senator Clinton throw Collins a bridal shower.

A turning point in the evolution of conservative womanhood came when John McCain selected a little-known governor of Alaska to be his running mate in his presidential race against Barack Obama in 2008.

Sarah Palin was in her mid-40s, young enough not to be collared by the pearls and propriety that inhibited many of her forerunners in both parties. She was charismatic and uninterested in conforming to outdated gender stereotypes. Or rather, she conformed to a bunch of them simultaneously: She had a sexy-librarian beauty and no qualms about playing it up; a macho snow-machine-racing husband who had taken a leave from his job on the oil fields to be the primary parent to their five kids; and she used her youngest child, Trig, born with Down syndrome, as proof of her hard-core anti-abortion bona fides. She had white-nationalist instincts that led her to counter Obama with language about “real Americans,” and she pioneered a Mama Grizzly persona that was both sporty and menacing (fuck your dead puppy; this lady wanted wolves to be shot from helicopters). She was unafraid to stake her own claim to women’s equality, advocating for a “new, conservative feminism.”

Balancing these divergent identities came naturally to Palin, and she was, at first, chillingly effective, the best to ever play the game of covering the cognitive dissonance of the right’s anti-woman policies with high-gloss girl power. What was the difference between a hockey mom and a pit bull? Lipstick, losers.

But if Palin was a model for a new generation of right-wing women, she was also a fundamentally unstable molecule.

McCain had hired Palin as a gimmick rather than as a colleague and thus had no idea what to do with her. His campaign fed her straight into the blades of the press, which exposed such deep ignorance of basic policy questions that Tina Fey could parody her on Saturday Night Live by simply repeating what she had said. But even had they prepared and protected Palin better, the combustibility of what she brought to the table was a preview of the metaphysical impossibility of women gaining real power on the right.

She was a star and then, almost immediately, too much of one. Palin’s poor media showing would be blamed for her ticket’s loss, but the eagerness to throw her under the bus surely stemmed in part from irritation: She had not been subservient. She had, famously, “gone rogue.” She had outshone the man at the top of the ticket.

The brutal irony of women on the right is that their emergence as mighty politicians is reliant entirely on feminist gains, and their experiences track with the feminist critique of inequality, including expectations of acquiescence to powerful men. Palin’s self-assured ethos was made possible by the women’s movement that she was interested in co-opting for herself — and which the modern Republican Party is seeking to destroy.

It was in the post-Palin flameout that the contours of that vengeful project would cease to be subtext and instead become mainstream conservative liturgy. The white-Christian-nationalist brand of Republicanism Palin embodied previewed the rise of the tea party and the right’s relentless drive to defund Planned Parenthood, an agenda accompanied by an open disregard for and cluelessness about women and their bodies.

During Obama’s first term, Republicans at the state level pushed through TRAP laws mandating that abortion clinics have wide hallways or that doctors tell patients about wholly fictionalized ties between abortion and breast cancer. Missouri’s Todd Akin proclaimed that in cases of “legitimate rape,” the “female body has ways to shut that whole thing down,” while radio host Rush Limbaugh said law student Sandra Fluke, who had testified in front of Congress about requiring contraceptive insurance for students, was a “slut” who was “having sex so frequently that she can’t afford all the birth-control pills that she needs.” This period saw the calcification of the Republican universe we now inhabit, in which, just this past February, Alabama senator Tommy Tuberville defended his state’s brief curtailment of IVF services by repeatedly insisting that the decision made sense because “we need to have more kids.”

The possibilities of earlier eras, in which a fiscal conservatism could be imaginatively walled off from social revanchism, thus mitigating contradictions for women like Snowe and Collins and Hutchison, were foreclosed by a post-Obama, post-Palin, post-tea-party right that was flagrant, excited even, about its ability to demean women. Some of the old-guard moderates, including Snowe and Hutchison, left their posts, while those who stayed began to turn right, in line with their ever more misogynistic party.

Valentina Gomez taking a flamethrower to sex-education books.

Photo: Valentina Gomez/Instagram

When the Republican Party of Palin first began to make way for the Republican Party of Trump, he was still best known as a reality-television star. He was the owner of the Miss Universe pageant, a serial adulterer who had cheated on two of his wives and was married to a woman who appeared to be his ideal: a simulacrum of every sculpted, shiny, glittery, enhanced expectation of femininity. Here was a man who regarded women with wolf-whistling lasciviousness or dismissed them as pigs and dogs. As a presidential candidate, he expressed revulsion for female bodies, claiming that debate host Megyn Kelly had “blood coming out of her wherever” and calling Clinton’s bathroom break during a debate “disgusting.” He was accused by more than a dozen women of sexual assault. When he became president, he stacked the Supreme Court with anti-abortion zealots who proceeded to strike down Roe.

For the women in his party who want to gain any political authority, submitting to him and conforming to his standards is the only path to survival, and womanly fealty to Trump can be vividly expressed by meeting the physical demands of his universe.

For years, the right promoted a very particular version of conservative femininity via its Fox News arm. Lithe blonde couriers of white panic over Black Santa and Sharia were one of Roger Ailes’s innovations, and Kelly, Gretchen Carlson, Laura Ingraham, and others gained powerful public perches in exchange for their chaturanga-toned arms and poisonous propaganda. That many of them would eventually come forward to tell of the grotesque harassment and sexual abuse they experienced while working at Fox is perhaps the ultimate portrait in miniature of the dynamic in which women on the right so often find themselves embroiled.

But if the sleek women of Fox were one model of idealized feminine aesthetics, this era demands a different look, one constructed not to Ailes’s tastes but to Trump’s.

Kristi Noem, like Palin, began her political life as a female herald of the hard-right turn her party was making, elected to the House of Representatives in the tea-party sweep of 2010. A former rancher, she came to office opposed to abortion and marriage equality. Noem was always classically attractive, a Jennifer Aniston look-alike who at the start of her political career worked a rural white middle-class-mom vibe: practical trousers, ill-fitting blazers, weed-whacked hair (there but for the grace of God go any of us).

Noem became a conservative superstar in 2020 when, as South Dakota’s governor, she refused to implement any COVID-mitigation efforts in her state. In 2021, the Times described “her eagerness to project a rugged Great Plains Woman image.” The next year, her first memoir, Not My First Rodeo, featured a cover image of Noem sitting astride a horse, in a cowboy hat and a red-white-and-blue western blouse.

In the years since COVID, in which the right’s affirmation clearly filled her with the ambition to ascend alongside Trump himself, Noem has undertaken an astonishing physical transformation. Gone are the boxy do and blazers; she now sports long, highlighted waves. Her cheekbones are angular, her lips pillowy, her eyelashes go on forever, and she wears body-skimming dresses. As Vanessa Friedman of the New York Times observed, Noem has begun “to resemble a doppelganger for Kimberly Guilfoyle” or “a dark-haired version of Lara Trump” — in other words, Trump’s kind of woman. “You’re not allowed to say she’s beautiful, so I’m not going to say it,” Trump said approvingly of Noem earlier this year.

Generations of women of both parties have been caught in this finger trap. When your value is tied inextricably to sexualized standards contrived by white men, you will not be appreciated, sometimes not even seen, unless you meet those standards. Yet if you do hit their (often shifting) aesthetic marks, you risk being degraded by those same men, not taken seriously as their peers but rather understood as their ornament.

In March, Noem cut an infomercial for the Texas dental practice that gave her a new set of front teeth. She said she wanted people “to focus on my thoughts and ideas,” instead of her allegedly flawed teeth, unconsciously echoing Granholm, who made herself dowdier for the same purpose. Thanks to the team at Smile Texas™, she continued, “I can be confident when I smile at people, and know that they can actually appreciate and see the kindness in my face and know the love I have for them.”

For Republican women less driven to cosmetic enhancement, there is another, more traditional expressive model still available: that of the demure maternal presence. Yet those working this angle are also plying their cozy wares in a manner that jibes with the despotic nihilism of Trumpian America, producing messaging that can feel like an unnerving subversion of maternal tropes as much as a reinforcement of them.

Katie Britt is the youngest Republican woman ever elected to the Senate, a 42-year-old mother of two married to a former NFL player. The pretty white straight woman dating the football player was surely once one of the conservative universe’s holy archetypes until gay-friendly Taylor Swift and her vaccine-loving boyfriend, Travis Kelce, scrambled conservative brains and sent a right-wing media into seething paroxysms of vilification and paranoia.

After the Swift-Kelce meltdown came Britt’s rebuttal to Biden’s State of the Union address, recorded in her home’s sparse kitchen, a glinting cross around her neck. Here was the remnant of the delicate and devout figure the right has long advertised as its heart and soul, the retro view of the comforting lady unadorned by anything but her love for Jesus, ready to make you dinner — while also working as a senator.

Then Britt began to talk. And out came a gruesome tale of how “the American Dream has turned into a nightmare for so many families.” If it weren’t for her eyelash batting, the speech would have been a direct callback to Trump’s inaugural 2017 address about “American carnage.” Britt told the story of a woman she’d met “who had been sex-trafficked by the cartels starting at the age of 12” and who’d shared with her “not just that she was raped every day but how many times a day she was raped.” (Freelance reporter Jonathan M. Katz would quickly identify the woman Britt was describing as Karla Jacinto Romero, an advocate who’d had this horrific experience between 2004 and 2008, when Republican George W. Bush was president, and not even in the United States.)

By grossly misrepresenting the experiences of a woman of color, Britt was working an age-old reactionary script of white American womanhood being vulnerable to violent sexual incursions by Black and brown people. Yet her fixation on the lurid details struck a contemporary note, one played often in the more conspiratorial corners of the right-wing internet, as if for a brief period she really had been possessed by the voices of Truth Social and was broadcasting them to the nation direct from her home in the uncanny valley. In fact, older videos would show that the breathy, baleful voice she adopted was nothing like her actual, perfectly normal voice.

Even Britt’s views on abortion, which are typical for a conservative Republican from the South, have taken on a more frightening cast. In May, she released a video advertising the MOMS Act, which she described, with a smile so aggressive it was audible, as a way to support Americans through “typically challenging phases of motherhood.” The bill’s approach to these challenging phases almost exclusively entails ensuring that no one ends a pregnancy: It includes the words abortion, terminate, and kill the unborn child 17 times but offers only two references to housing and three to childcare.

Use of the white mother figure in the past was meant to signal the preservation of the private family sphere from the purported overreach of government: no federal officials reaching their sticky collectivist fingers into your home, telling you how to raise your children. But now, empowered by Dobbs, Britt’s motherly warmth was being deployed on behalf of a government project that would gather information about location, menstrual cycles, and pregnancy on behalf of a party that would like your friends to turn you in if you end that pregnancy. It recalled the hissed threat of Britt’s State of the Union response: “We see you; we hear you.”

Perhaps no elected official embodies the contortions of the modern Republican woman more than Mace, who was first sworn in to the House of Representatives on January 3, 2021. Three days later, her workplace was under attack by insurrectionists, anathema to a woman raised on military order. Her father was commandant of the Citadel, the South Carolina military academy of which Mace, in 1999, became the first female graduate. She denounced Trump after January 6, telling CNN the president’s “entire legacy was wiped out” by the coup attempt and later arguing that “we have to hold the president accountable for what happened.”

The Citadel shaped Mace’s identity in more ways than one. Her 2001 book, In the Company of Men, tells the story of her experience there: the scrutiny of her physical presentation, sexist intimidation, harassment. This is a politician, in other words, who has thought a lot about gender, power, and inclusion. When we spoke in May, she smiled at me warily and said, “Yeah, in the party, I’m a unicorn.” She has, for example, announced her intent to work on legislation with Democrat Ro Khanna to make child care more affordable. “Collectively, as a party, we’re not traditionally seen as pro-woman, and I’m trying to change the narrative,” she said. “It’s a rather lonely experience.”

Mace is enthusiastically anti-abortion but broke with her party when she was in the South Carolina legislature during a 2019 debate on a fetal-heartbeat bill that included no exceptions for rape or incest. “No one was talking about rape,” she said. “I felt shattered as a woman because I am a rape survivor.” Mace had been sexually assaulted at 16. “I took the microphone and went to the well, and I gave a speech I never thought I would ever give,” she said.

Mace’s story mirrors the 2013 experience of then–State Legislator Gretchen Whitmer, who, in the midst of a Michigan senate debate over a bill requiring separate health insurance for abortion coverage, surprised herself and advisers by putting her notes aside and speaking extemporaneously about how she had been raped more than 20 years earlier. But for Whitmer, a Democrat, her firsthand experience of assault and its connection to abortion access fit seamlessly with the rest of her politics. For Mace, the connections are far harder to draw.

“I’m a pro-life member in a pro-choice district,” said Mace. “I’m willing to find common sense and common ground. When we knew Roe was going to be overturned, I went straight to the microphone; I went straight to writing op-eds, doing interviews, being the voice of reason. Because I saw the visceral reaction in my district and I said, ‘I’m not leaving these women behind.’” Her solution, she said, is a ban at “somewhere between 15 and 20 weeks.” In 2023, Mace introduced a bill to protect contraceptive access, calling it “just common sense.” She introduced a resolution denouncing the Alabama IVF ruling, a position she called “a no-brainer.”

Back in 2021, Mace did not, ultimately, vote for Trump’s impeachment. But he remembered the slight of her initial rebuke and endorsed Mace’s 2022 primary challenger. Mace tried to win him back by traveling to Trump Tower and posting a video documenting her devotion to him; he responded by calling her a “grand-standing loser.” Mace survived her reelection bid thanks in part to the backing of Trump’s future primary rival, former South Carolina governor Nikki Haley.

When I asked Mace if there were any women in politics she regarded as models, she replied, “I respect the hell out of Nikki Haley. She has shattered glass ceilings her entire life. She has stayed true to her values and her principles; I think she’s a remarkable woman.” Yet in January, Mace endorsed Trump over Haley. “I respect her so much,” Mace said when I asked her about this incongruity. “But I could see as clear as day that Donald Trump was who South Carolinians want, hand over fist.”

She also insisted that “Donald Trump is good on women’s issues. He was the most pro-woman candidate in the presidential primary. And he gets it.” Never mind that Trump has called the end of Roe a “-miracle.” He poohpoohs claims that he would restrict contraceptive access one day and say he’s open to state restrictions the next. He has called the state-by-state fight over whether abortion will remain accessible “a beautiful thing to watch.” It is very difficult to maintain a moderate keel through rhetorical gates like this.

Here is the quandary of the ambitious Republican woman laid bare. Mace’s history and profile — her time at the Citadel, her experience of assault, her admiration for the women who paved her way into politics, her self-professed moderation on abortion — might have put her in a position to reclaim the “new conservative feminism” Palin had staked out. Much of that gets warped by the pull of Trump and his politics of domination, a centripetal force that demands the breaking of bonds with mentors, adherence to day-is-night lies and inconsistency, the humiliating recanting of past criticisms, and de facto support of an abortion agenda more extreme than it has ever been. Mace’s efforts were rewarded: In 2024, Trump endorsed her and she won her primary bid on June 11 by 27 points.

There is surely a perverse pride in emerging victorious near the top of a power structure built to exclude you. These are the dynamics that have long rewarded white women for acting as foot soldiers within a white patriarchy, willing to take one another out to get closer to power, their positions adjacent to the brutes at the top a signal of their uncommon tenacity. But there is a difference between the status granted those willing to do whatever unhinged thing it takes to get ahead in contemporary right-wing politics and the political autonomy these women might yearn for just as much as the classical feminists they wage war against.

When Valentina Gomez agreed to respond to my emailed questions, I noted that she had used “MAGA” to describe her politics and wondered whether she saw a distinction between MAGA and the Republican Party. “I do not use MAGA,” Gomez corrected me. “I am MAGA and The Future of the Republican Party.” Gomez told me she developed her political ideals while swimming Division I, graduating from college at 19, earning an M.B.A. at 21, and “building a real estate empire with my family” — all achievements enabled by the feminist movement. But, she said, “feminism is exactly like the Trans Movement, they are both doomed.”

Mace too turned to certain tools of feminist argument. During the Hunter Biden “no balls” hearing, she used the language of grievance when she was interrupted, asking, “Are women allowed to speak here or no?” In our conversation, she criticized former Speaker Kevin McCarthy for pushing only one “major women’s bill” (as it happens, a piece of anti-trans legislation). Mace went on, “I can’t tell you how offensive that was as a Republican woman knowing how important women’s issues were going to be. His chauvinism was ridiculous. And his misogyny and sexism.”

Mace also cried misogyny when ABC News’ George Stephanopoulos asked her during an interview how, as a rape survivor, she could support Trump. And while it is true this question should be addressed to all supporters of Trump, not just those who have experienced sexual assault, Mace deflected the challenging question by claiming Stephanopoulos was “rape-shaming” her.

In the past, it was easier for Republican women to get away with inconsistency and self-contradiction. Phyllis Schlafly, the brilliant, diabolical political strategist, could inveigh against the masculinized ambitions of women working outside the home from pulpits well outside her own home because her professional efforts paid lip service to restoring certain comforting hierarchical expectations about men’s and women’s spheres.

That paradigm has been subverted. What Schlafly and her generation feared most — that the expanded opportunities and protections for women would become their own kind of traditional expectation — has come to pass. This is why the overturn of Roe was not greeted as some welcome restoration of a bygone order but as a threatening attack on the protections that plenty of American women, especially white middle-class women of all political persuasions, had come to count on as an established norm during the 49 years Roe stood.

Every one of these Republican women relies on the gains of women’s liberation, and well they should. This was, in fact, what the women’s movement was for: not just so those who agreed with it might enjoy more opportunities but so those who did not agree with it also could. As an early political ballbuster, former New York congresswoman Bella Abzug famously said, “We don’t want so much to see a female Einstein become an assistant professor. We want a woman schlemiel to get promoted as quickly as a male schlemiel.” Welcome, ladies.

Remarkably, these dark years have seen women on the left conduct themselves with new ease and assuredness. Democratic women at both the center and the left edge of their party now communicate in a range of styles that appear more authentic and less stilted than those of previous generations of female politicians. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez is fluent on social media; Elizabeth Warren lets her professorial freak flag fly; Ayanna Pressley is bald and beautiful. They tell stories of abortion, of assault, of pregnancy and childbirth, of their gay and trans offspring, of their disabilities and military service, weaving the facts of their lives into arguments for civil rights, health-care access, and housing.

Whitmer is perhaps the most prominent Democratic woman to experiment with mixing a traditional white femininity and historically masculine cadences. Though her politics could not be more different, she is perhaps the closest we have yet seen to a natural echo of Palin’s swashbuckling cheek. In May, Whitmer wore a fuchsia wrap dress to pick up an award for a campaign she undertook as “Governor Barbie.” Her five-word acceptance speech was “Wear pink; get shit done.” In the days after Noem’s disastrous book tour, Whitmer took a break from posting about the NFL draft to put up a photograph of her with her two dogs, Kevin and Doug, with the caption, “Post a picture with your dog that doesn’t involve shooting them and throwing them in a gravel pit.”

It’s certainly all performed in its own way. But for the first time, it’s the Democratic women who can articulate the mix of football and Barbie and health care and labor without tripping over themselves, who seem more comfortable in their own bodies. The women on the right appear in perpetual confusion and find themselves, like some negative image of Clinton, twisting into something unrecognizable.

There is nothing inherently wrong with wearing pink and making testicle jokes. Though shooting dogs is not nice and giving hand jobs during Beetlejuice is rude, they are part of a range of impulses a free society should be open to evaluating on their own merits, regardless of the gender of the person engaging in them. If you could separate it from the regressive politics, there might be something exhilarating about Marjorie Taylor Greene’s willingness to throw weights around and toss off suffocating norms of feminized civility in the workplace.

But there is no way to understand these varied approaches to gender expression outside the context of their own political aims. These are politicians who regularly refer to gender-affirming health care as “castration” and “mutilation.” Boebert famously campaigned against drag story hours, while Noem wrote to South Dakota’s college board asking it to ban campus drag shows. Republican women longing to attach themselves to the feminist brand leverage transphobia to do it, a riff on the TERF movement currently flourishing in the U.K. Mace has argued that conservatives laboring to keep trans women out of athletic competitions are “the feminists of today,” and Haley has cast anti-trans policymaking as the “women’s issue of our time.”

Yet these women express themselves via a dizzying mash-up of gendered conventions: They augment their smiles, bedazzle their pantsuits, and broadcast their bench presses. In their fevered performances of hyperfemininity and hypermasculinity, so many of the GOP’s most visible women are themselves engaging in a form of drag.

Of course, drag in its queer context offers the chance to slip from and send up the constricting bounds of gender norms, to encourage empathy and celebrate diverse forms of identity. The show these Republican politicians are putting on is its cold opposite: asphyxiated, distended, nasty. Theirs is surely drag’s gothic inverse.

Still, it is possible to catch a glimpse of pathos beneath the performance because the show covers for something awful and real: The identities of those women are no more valued or recognized by the party for which they labor than gay or trans or feminist identities are. Women fundamentally cannot lead a party that wants to oppress women; they cannot, in fact, even be fully human within it.