In the history of toys, there haven’t been many that have met the craze and frenzy created by the Hula-Hoop.

| Photo Credit: Andrew David Newdigate / flickr

When do you grow up? Is it when you become tall enough that you can reach the highest shelves, even fetching stuff for others in the household on occasions? Or, is it when you put on enough weight to be able to lug around things when needed? Or, are you considered grown up when you stop playing with toys?

There’s no one way to answer our initial question, really. But if we are going to take the final parameters suggested as our means to find out, then American inventors Arthur Melin and Richard Knerr never grew up! They surely did grow up, obviously. But they remained children at heart as they went on to spend a lifetime with toys.

Boyhood friends

Born within six months of each other (Melin was born on December 30, 1924, Knerr was born on June 30, 1925), Melin and Knerr were boyhood friends who went to the University of Southern California together. Breeding falcons was a hobby that they shared at this point, and training the falcons to dive was something that they relished.

They did this by lobbing meatballs at them on the wing, which they achieved using a home-made version of a slingshot as their projectile launcher. While they tried to sell their birds to enthusiasts without much luck, they got more traction for their launcher instead.

Wham-O is born!

As both of them weren’t too keen to join in their fathers’ businesses, they decided to make the most of the interest people showed in their slingshots. With a $7 down payment at Sears, Roebuck & Company, they purchased a power saw and set shop in Knerr’s parents’ Los Angeles garage. While Melin cut shots with the saw, Knerr sanded it and they were both involved in the business of selling it – first personally, and then through postal orders countrywide. The Wham-O Manufacturing Company was thus born in 1948.

They called it Wham-O for the sound a slingshot made when it hit its target. They expanded slowly, first moving out of the garage to a failed grocery store, before eventually becoming big enough to set up a factory. While they set out focussing on sporting goods, they flourished in the toys industry. They remained informal about their business throughout, even when they enjoyed tremendous success.

Frisbee frenzy

Their first major breakthrough came through a product that they bought in, the Frisbee. They came across Walter Frederick Morrison, who was trying to sell his flying discs in a parking lot in 1955. They bought the rights to what Morrison called Pluto Platters and got Ed Headrick, their research and development man at Wham-O, to add aerodynamic details like the rings on the top.

It wasn’t until 1958, when it was renamed Frisbee, that the product picked up in terms of sales. With slow and steady sales, it turned out to be one of the most popular toys from Wham-O’s stable, and it continues to remain relevant till this day. Just as Melin hoped, it has even formed the basis of a sport called Ultimate, which even has world championships now.

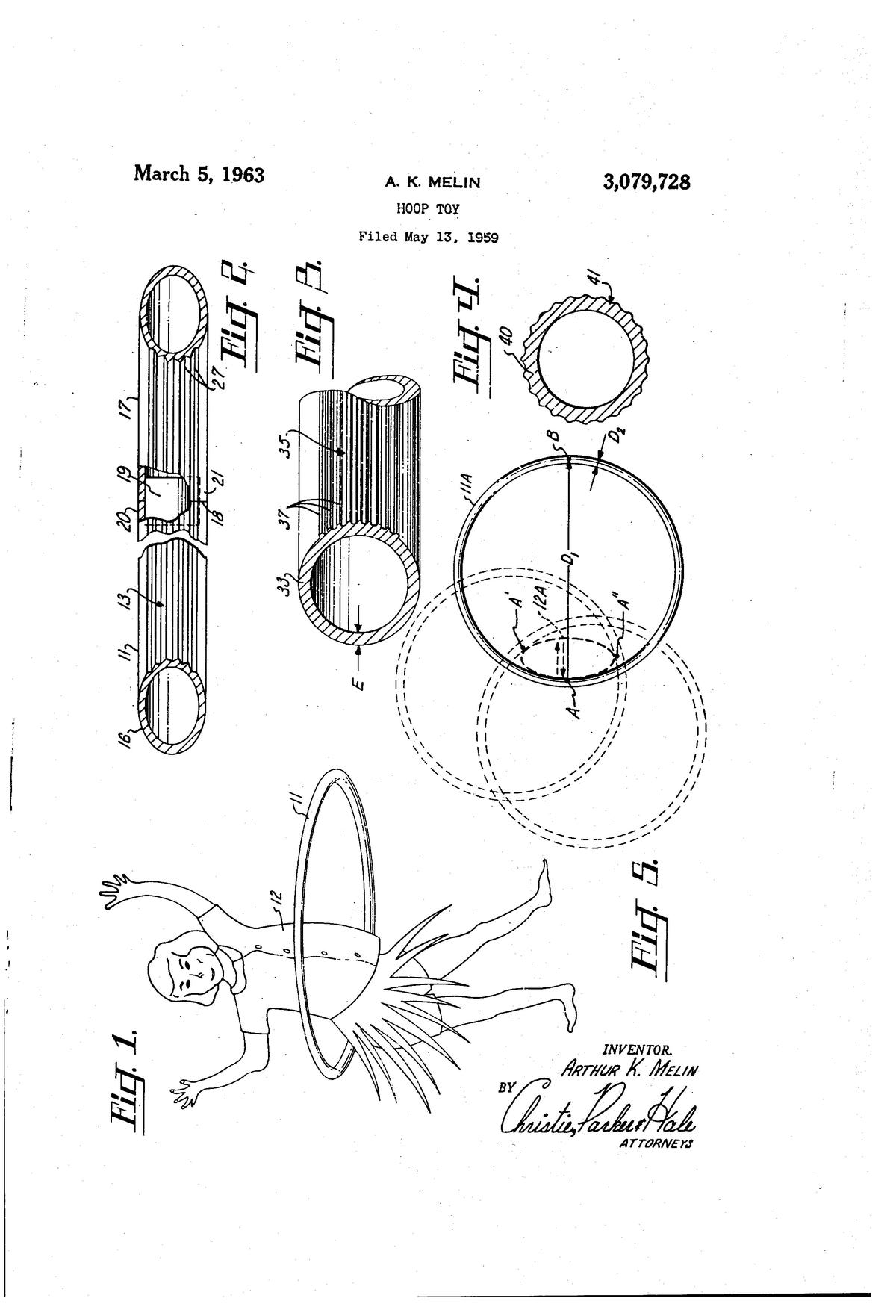

The patent drawings used for the Hula-Hoop. Melin’s name is mentioned as the inventor.

| Photo Credit:

US Patent US3079728

Hula-Hoop effect

Their biggest success, even if not financially, was the Hula-Hoop. According to company legend, the idea came to them when a visiting Australian told them about how they rotated a bamboo hoop around their waists as children in gym classes. Seeing its potential, they set about manufacturing what they called the Hula-Hoop using high-density polyethylene (HDPE), a plastic newly developed by the Phillips Petroleum Company.

An entire nation was taken by storm as Wham-O’s Hula Hoop and countless other imitations went off the shelves at an unbelievable rate. Wham-O sold anywhere between 20-40 million hoops in the first year alone (1958) and reached the 100 million mark – something unthinkable for most toys – by 1960. The fad, however, ended as quickly as it started as each household had two or three of these! Business inexperience and a mountain of plastic in the form of unsold hoops, meant that Wham-O didn’t make a killing from their Hula Hoop.

Bounce back like a Superball

They bounced back from that financial debacle with the Superball, 20 million of which they sold before dropping the product. It was made of compressed plastic called Zectron that bounced uncontrollably, something that a chemical engineer had accidentally come up with. It took them two years of development to overcome its tendency to fly apart and create the Superball.

For as long as they remained in business, Melin and Knerr kept tinkering and inventing. The patent for a water play toy filed by Melin on June 23, 1980 was probably among the last few toys that Melin and Knerr were involved with. Growing weary of business, Melin persuaded Knerr to sell the company in 1982, the same year when they received the patent for the water play toy.

Even though they had grown tired of business, they hadn’t grown tired of toys. Melin in particular kept up his interests in inventing and even patented a design for a two-handed tennis racket with an adjustable handle. After a lifetime of creating crazy stuff that they were able to sell world-over, Melin and Knerr died in the first decade of the 21st Century – Melin in 2002 and Knerr in 2008.