White-nose syndrome has been found in bats in the largest known hibernation area in the province.

The Alberta Community Bat Program, an organization that works to protect bat populations and raise awareness about them in general, says the disease was confirmed in three little brown bats, in two separate locations, along the Red Deer River badlands.

But it’s believed the disease is affecting a much larger number.

“Little brown bats are the most common bat in Alberta. If we lost them it would be a tremendous loss,” said Cory Olsen, the Alberta bat program coordinator for Wildlife Conservation Society Canada.

White-nose syndrome is one of the worst wildlife diseases ever recorded. It’s already killed millions of bats across North America.

The disease is caused by a fungus found in caves where bats hibernate.

Olsen says the fungus was first discovered in the badlands near Dinosaur Provincial Park in 2022, but this spring is the first time bats have tested positive for the disease.

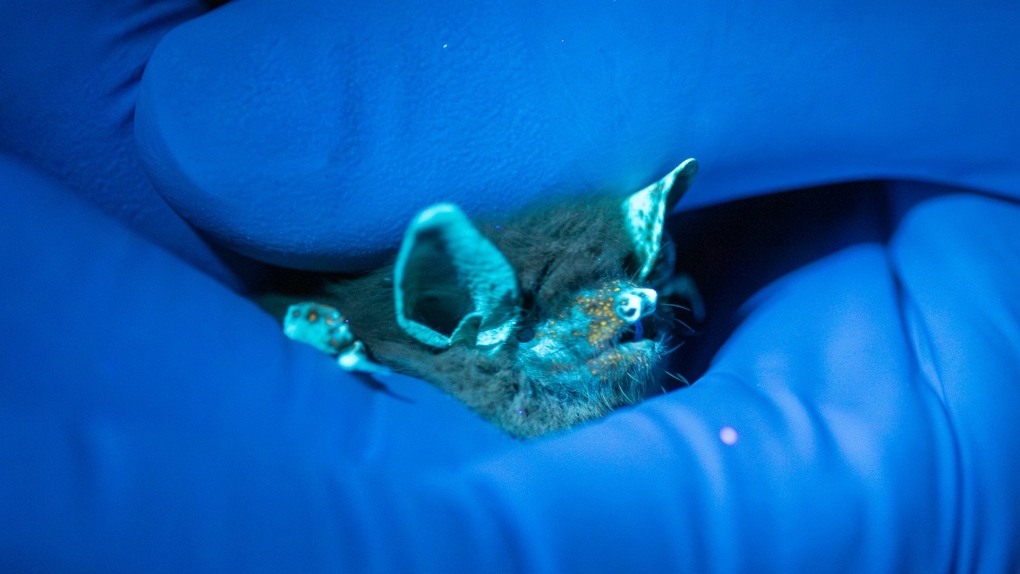

A collaboration between Wildlife Conservation Society Canada and Alberta Environment captured bats as they emerged from hibernation in early May. Tissue samples, scarring and fungus on the bat’s wing confirmed white-nose syndrome.

Officials say monitoring is now underway to determine if white-nose syndrome is resulting in a decline in the brown bat population.

Bats are the top predator of insects that fly at night and are important for the ecosystem and biodiversity, Alberta Bats says.

“Nobody has calculated the value of bats in Canada, but in the U.S., their value to agriculture is $23 billion a year,” Olsen said.

With fewer bats, U.S. farmers are paying billions more in pest control. As the fungus spreads, there’s concern Prairie farmers will face the same problems.

There is currently no cure for white-nose syndrome, but according to the province there is evidence some bat species in eastern North America are developing a resistance to the disease.

There are a number of projects underway to better understand the fungus.

“A probiotic cocktail containing beneficial microbes to inoculate bats is currently being tested in Washington,” said Olsen. “As part of the work in Alberta we collected samples of the microbe that occurs on the bat wings…and we’re providing samples to McMaster University where they are also working on a probiotic cocktail.”

(Supplied/Alberta Bats)

(Supplied/Alberta Bats)

On its website, Alberta Environment says the fungus can’t be prevented or eradicated, but bat populations can be helped by protecting their key habitats.

“Maintaining places for bats to roost, hibernate and forage will help populations recover after initial declines.”