Hello! Eurogamer is once again marking Pride with another week of features celebrating the intersection of LGBTQIA+ culture and gaming. Today, Dr Lloyd (Meadhbh) Houston reflects on what learning more about their neurotype has taught them about gaming and queerness.

This article is about coming out, though not in the way you might expect.

Last year, following a period of burnout and a lot of conversations with neurodivergent friends and loved ones, I began the process of seeking a diagnosis for autism. It feels right to discuss this publicly for the first time in the context of a Eurogamer Pride Week piece. My queerness, my neurotype, and my love of gaming are intimately connected in ways that I’m finally in a position to make sense of and to celebrate, and Eurogamer and the community it has fostered have played an important part in that journey.

In sharing my experiences like this, I’m not aiming to make a one-size-fits-all statement about autism and its relationship to queerness or gaming – as the saying goes, if you’ve met one autistic person, you’ve met one autistic person – and I’m conscious that, as a white, able-bodied, university-educated person with low support needs, my experience of neurodivergence is informed by a great deal of privilege. Instead, I want to offer some personal reflections on what learning more about my neurotype has taught me about gaming and queerness, and how embracing the queerer side of gaming has helped me to embrace my autism. Expect some info-dumping!

Autism and queerness have an entwined history. This is partly because of the high proportion of autistic people who identify as LGBTQIA+. It is also because some of the most prominent and traumatising “treatments” for autism, particularly Applied Behavioural Analysis (ABA) programmes, were developed in close conversation with “conversion therapy” practices that seek to “correct” gender non-conformity and other forms of queerness through punishment and coercion. Amazing work has been done by disabled scholars, activists, and community organisers to chart this history, and to expose and challenge the ways that compulsory heterosexuality, compulsory able-bodiedness, and compulsory able-mindedness serve to reinforce one another to the detriment of everyone in society. This work has increasingly come to be discussed in terms of neuroqueering.

At a personal level, my autism feels closely linked to both my transness and my bisexuality. Despite being assigned-male-at-birth, the forms my autism take deviate from the “Extreme Male Brain” conceptualisation of the neurotype that remains (regrettably) popular in scientific circles, aligning more closely with those increasingly being identified among people who are assigned female at birth. These are more likely to go unnoticed due to high levels of “masking” – the exhausting process by which autistic individuals try to blend in by prioritising the needs and comfort of others, and by minimising or redirecting autistic tendencies like hand-flapping (“stimming“) into more socially acceptable forms like hair-twirling.

As you might expect given that my brain has essentially noped out of normative masculinity, supposedly “natural” social norms like binary gender and reproductive heterosexuality make very little intrinsic sense to me, and, as with many other aspects of my neurotype, I no longer possess the energy or inclination to conceal this fact. Gaming has really helped with this.

Discussions of gaming and autism sometimes take the form of explorations of how games can help autistic people “overcome” their various perceived deficiencies by simulating neurotypical behaviour. Stimming hands are quieted. Fine motor skills are honed. Conversational turn-taking is mastered. However, in the spirit of neuroqueering and Pride more generally, I’m less concerned with the ways that gaming can help people like me to appear more “normal” than I am invested in the ways in which gaming can afford us a space to be more fully and authentically ourselves. I am interested in gaming not as corrective and “cure”, but as a tool for unmasking.

Perhaps the most obvious starting point for thinking about gaming in this way is the passion it inspires in those who love it. Special interests, hyperfocuses, or, to use the pathologizing language of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, “perseverations”, are some of the most widely-recognised features of autistic experience, and there are few interests as special, for me at least, as gaming. Anyone who has read my contributions to Eurogamer’s Pride Week series will be able to identify my hyperfocuses without difficulty: Final Fantasy 7, survival horror, cyberpunk – a list to which I’d add series like Metal Gear Solid, Fallout, and Baldur’s Gate, and virtually all immersive sims. Basically, if it features ambiguously gendered hotties in harnesses for me to romance, camp monstrosities for me to (pretend to) flee from, or a deeply-storied world in which to immerse myself (preferably while stacking crates), I’m there.

While these aren’t games or franchises that feature much by way of explicit autistic representation – something that gaming is only beginning to offer through characters like River in To the Moon or Symmetra in Overwatch – they are games that resonate with and reward what I’ve come to recognise as my neuroqueer mindset. As a literary scholar, I recognise that Hideo Kojima’s fetish for over-elaborate, hyper-technical exposition can leave his games feeling less narratively balanced than an all-terrain, nuclear-equipped, walking battle tank pole-dancing in Louboutins. As an autistic person, however, I could listen to a character whose name sounds like an imploding dictionary discuss the intricacies of meme theory, bullpup assault rifles, and cardboard box manufacture for days. The detail-saturated quality of the worlds Kojima builds makes my brain happy (even if his handling of female characters often doesn’t).

In daily life, I’ve been made to feel self-conscious about the depth of my enthusiasm for interests like gaming. The faintly mortified or glazed-over expression of friends and acquaintances that would greet my latest monologue about SHODAN, GLaDOS, or whichever digital diva I was stanning at a given moment was one of the reasons I basically stopped playing games through most of my twenties. But reconnecting with gaming during the pandemic, both through Eurogamer’s video streams and a Google Stadia subscription (of all things), reintroduced me to a world where my level of engagement wasn’t unusual or embarrassing. Enthusing about, analysing, and debating the queer elements of these games in conversation with members of the Eurogamer community through pieces like this one, and having these discussions spill over into in-person gatherings like EGX, were affirming acts of unmasking, even before I knew that’s what I was doing.

This sense of unmasked connection is another crucial aspect of the relationship between autism, queerness, and gaming for me. In the popular imagination and clinical literature, autism is often framed as a state of pathological self-involvement, impaired social communication, and compromised capacity for empathy and imagination. Autistic people, we are told, are “mind-blind”, lacking the ‘theory of mind’ that would allow us to understand that other people have feelings, desires, and beliefs different from our own – a perspective that neuroqueer writers and autistic self-advocacy groups have forcefully challenged.

My experiences in gaming have confirmed for me that, far from lacking empathy, autistic people are intensely concerned with how others are thinking and feeling, and eager to explore and inhabit their minds and experiences, albeit in ways that neurotypical culture often fails to empathise with or understand (giving rise to the so-called “double empathy problem“).

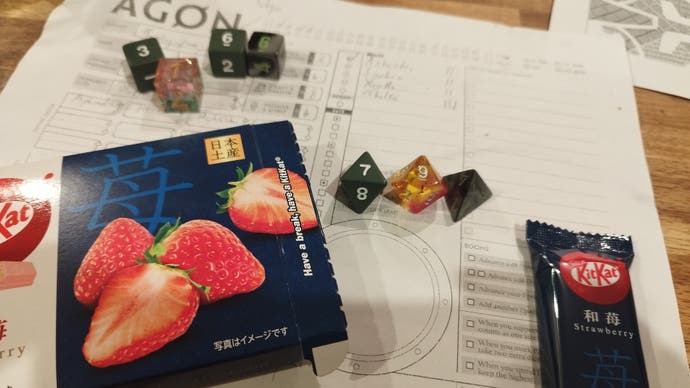

One of the most joyfully neuroqueer experiences of my life was having the opportunity to guest in a session of Greek mythology table-top RPG Agon, hosted by fellow Pride Week regular, Sharang Biswas, during a trip to New York. I joined the crew as they were about to enter the underworld to rescue their ship’s cabin twink, with whom most of the polyamorous player characters were somehow sexually or romantically involved.

As Sharang narrated how my whip-wielding, leather-clad avatar “Topping-from-the-Bottom” Metrophanes gratefully took their place as the eternal footstool of their patroness/domme, Hera, after accidentally immolating themselves at the session’s chaotic climax, I found myself stimming with delight at the sense of having achieved something that popular and clinical stereotypes of neurodivergence would suggest should be impossible for people like me: working collaboratively with a group of familiar and unfamiliar faces to fashion a gleefully queer narrative premised on imagination, play, and shared insight. Crucially, in conjuring this story together and yes-and-ing our way to its hilariously unforeseen conclusion, none of us had been obliged to conform to any particular mask or mode of expression or behaviour. In fact, it had only worked so well because we had all been free to be completely ourselves.

The hopes, dreams, and struggles of queer people and neurodivergent people are not always identical, but they are closely entwined in ways that should be a cause for pride and celebration, and which should form the basis for collective political action and social transformation. A world that accommodates and cherishes the full range of human neurodiversity is, necessarily, a world that also accommodates and cherishes the full range of gendered and sexual diversity, and vice versa. As I’ve tried to sketch out here, at its best, gaming, both in the imagined universes it generates, and in the neuroinclusive forms of sociability and community it facilitates, can help bring that world a little bit closer.

Like everything in life, my relationship with my neurotype and my queerness are works in progress, but, this Pride, through gaming, I am delighted to be playing with both.

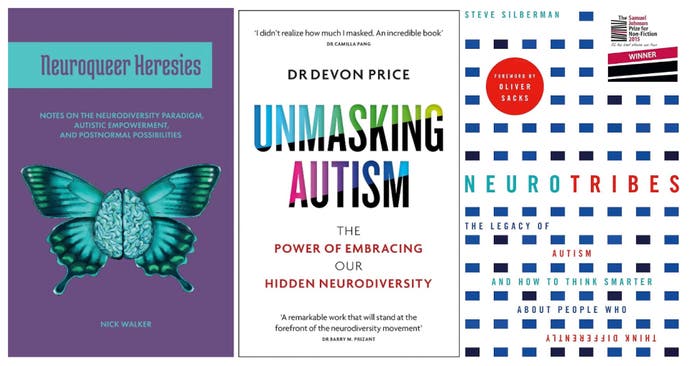

Further Reading and Resources:

There is a rich and growing body of writing by autistic people about many of the topics touched on in this article. For an overview of the neurodiversity paradigm and neuroqueering in theory and practice, check out Nick Walker’s Neuroqueer Heresies (2021) and her website, where she regularly posts new work. For more on radical unmasking and the relationship between queerness and autism, I’d recommend Devon Price’s Unmasking Autism (2022). For a history of autism and autistic culture, pick up Steve Silberman’s NeuroTribes (2015). For resources and discussion on gaming and neurodivergence, have a look at Accessible Gaming Quarterly. The National Autistic Society offers a rich array of information on and support with autism from a neuro-affirmative standpoint.