Scientists have developed a new test that can diagnose deadly bacterial infections and identify the most appropriate antibiotic to treat them more than two days earlier than conventional approaches can.

Reducing turnaround times from infection to treatment could save patients from dying of sepsis, a serious condition in which the body overreacts to an infection, triggering tissue damage and organ failure. Once sepsis sets in, it can kill a patient within 12 hours. The goal of the new test is to identify the bacterial target quickly so the infection can be snuffed out before it advances to sepsis.

The test could also help curb the overuse of broad-spectrum antibiotics, meaning drugs that kill a wide range of bacteria. Broad-spectrum antibiotics can be useful when the exact culprit behind an infection is unknown. But the drugs can also fuel antibiotic resistance, pressuring microbes to evolve so they can survive the treatment.

The new test could help doctors pick the right “narrow-spectrum” drug faster, thereby reducing doctors’ reliance on broad-spectrum solutions, according to the researchers who developed it. They described their findings in a paper published Wednesday (July 24) in the journal Nature.

Related: Dangerous ‘superbugs’ are a growing threat, and antibiotics can’t stop their rise. What can?

Normally, if a doctor suspects that a hospitalized patient has a bacterial infection, they will start the patient on broad-spectrum antibiotics before sending a sample of their bodily fluids for antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST). This sample is taken from the site of the infection; for instance, urine would be used for a suspected urinary tract infection and blood for a suspected bloodstream infection.

This sample is then cultured in a lab, meaning it’s stored such that the microbes within it can grow and multiply to the point that they can be detected by a test. Then, after a culprit bacterial species is identified, scientists test a range of antibiotics at different concentrations to determine which formula works best. At that point, the patient would be switched to a more-targeted treatment.

These steps currently have to be done separately using different equipment, so the whole diagnostic process can take more than three to four days, said lead study author Tae Hyun Kim, who was a postdoctoral scholar at Seoul National University in South Korea at the time of the research.

Testing may also be limited to regular lab operating hours, potentially leading to “missed critical treatment windows” for sepsis, Kim told Live Science in an email.

Kim and colleagues claim that their new diagnostic approach, which they’ve dubbed ultra-rapid AST (uRAST), can complete all the tests needed to prescribe the most appropriate antibiotic for a patient “within a day.”

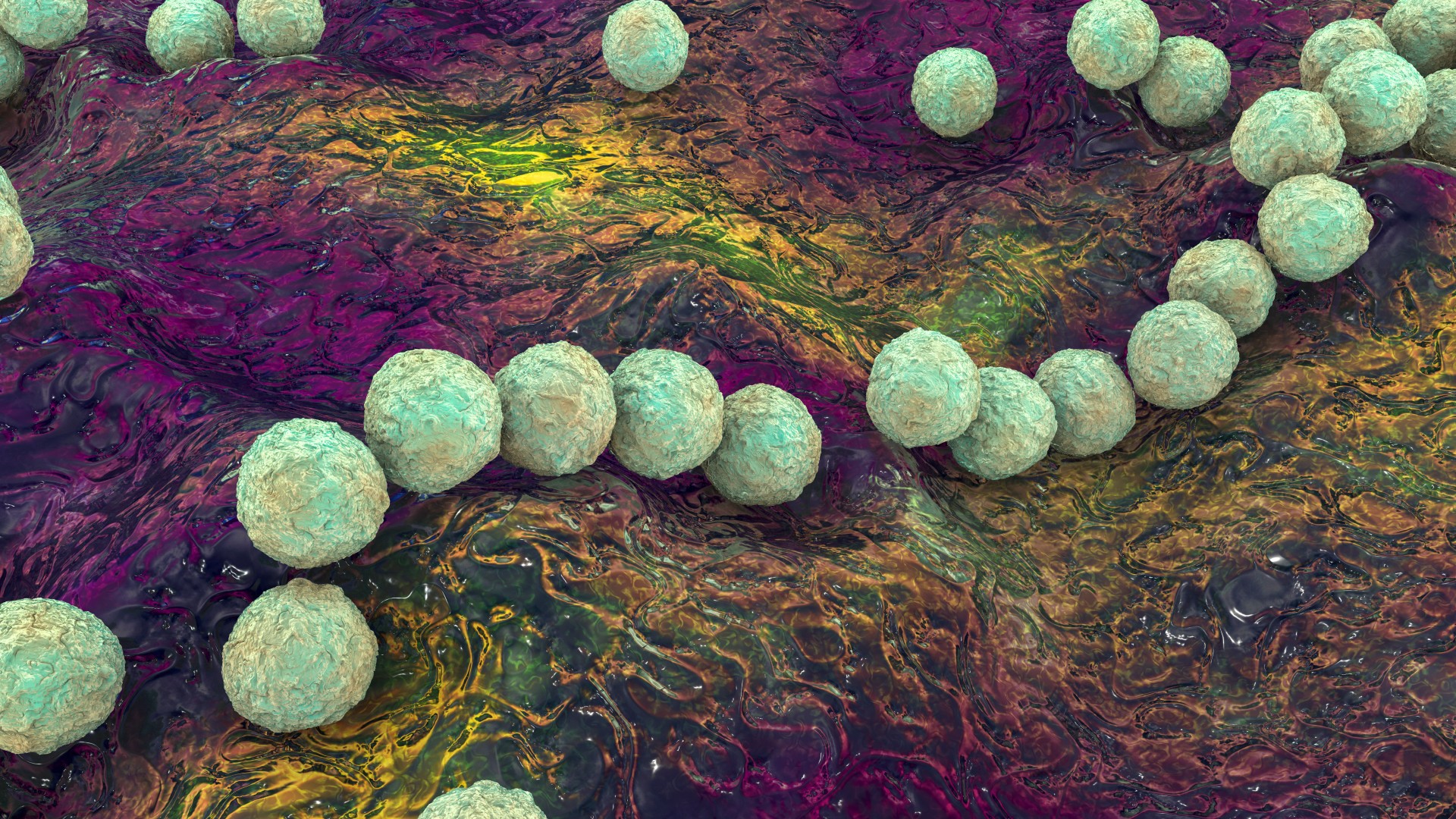

Unlike conventional AST, uRAST can isolate pathogens within a sample of a patient’s blood without the need to culture it first. It does this using nanoparticles that are coated with a small protein that can bind to a broad range of pathogens. Once the nanoparticles have latched onto the bugs, some of the purified sample is then used for species identification. At the same time, other portions of the sample are tested for antibiotic susceptibility.

In lab experiments with human blood, the team found that uRAST could reduce the turnaround time from infection to antibiotic selection by 40 to 60 hours. They directly compared the new test with traditional AST approaches.

After these experiments, the team also tested the effectiveness of uRAST in a group of 190 hospitalized patients with suspected bacterial infections. Eight of the patients ended up positive for bacteria, and the test correctly identified the species responsible in all of these positive cases.

In a separate experiment, the team exposed stored blood to strains of bacteria that had been collected from six of these positive cases; they did this to retrospectively test how useful the uRAST test might be in a clinical setting. They ran the test and found that the average turnaround time from initial blood processing to identifying an appropriate antibiotic was around 13 hours.

The team now plans to merge the individual components of the uRAST test into a fully automated, all-in-one device, Kim said. The accuracy and reliability of the device would then need to be assessed in large-scale clinical trials before it would ever be rolled out in hospitals. If cleared for use, it could represent a significant step forward.

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line “Health Desk Q,” and you may see your question answered on the website!