The light in Venice teases and tempts the photographer, makes them look inwards.

I am the man stilled

in a landscape racing past me

So much remains still. So much remains in a state of almost-born. We know this in the case of thoughts. Or in my case, images. My constant battle between the analogue and the instant nature of the digital or the phone-chimera. That which excites even as it obliterates. Leaving very little room for “living”, that stretched period of anxious time that creates suspense.

I bring you back to my first encounter with the Stoppardian suspense. That startling opening of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead. R & G, having lost their way into a limbo somewhere between Shakespeare and Beckett, are seen tossing coins. Guildenstern remarks: “There is an art to the building up of suspense,” flips a coin, then continues, “though it can be done by luck alone.” One of the two characters is aware that the coin is, in fact, two-headed. So there is no way the spinning can change the fate of the coin or of the character. And yet, what if? This “existential” suspense is our modern-day condition. As in, despite the knowledge of the odds being stacked against us, there is a tiny window of hope.

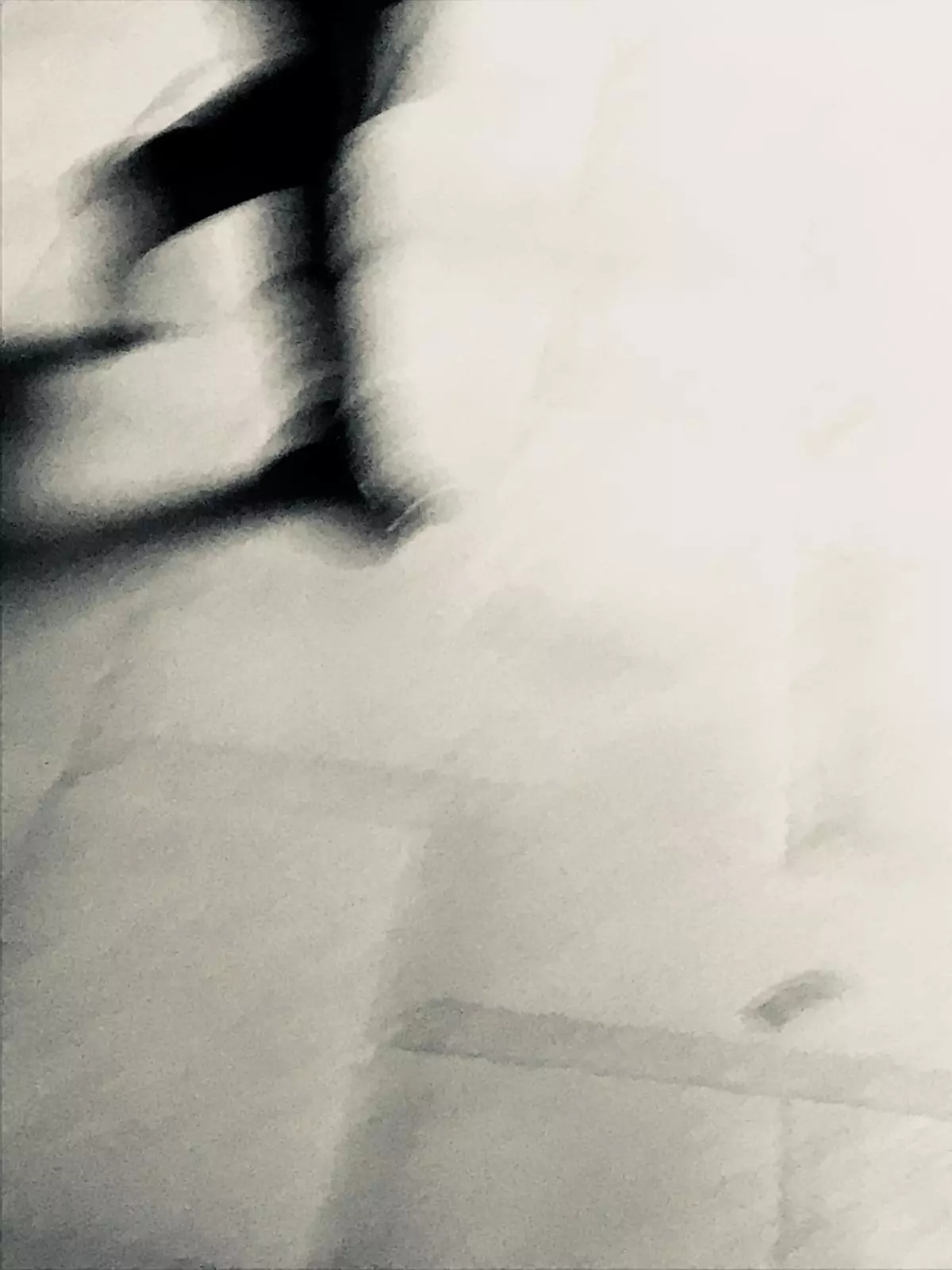

The photographic suspense I speak of is somewhat in the nature of a moment paused. An act of almost-revealed. Not by accident. But by design and purpose. Perhaps even with some degree of motivation, as in Pinter’s plays. The Pinteresque pause anticipates in that moment of imposed-suspense a limbo that is full of everyday menace at one level and a vast melancholic helplessness at another. But. We know that the pause will create an active (or passive) moment of decision. Choice. For the character. One which implies the desire to act. Or to not do anything. Either because all has been numbed or because every act implies a risk-taking. You don’t want to take a risk. You let time step in—perhaps in the guise of circumstance—and choose for you. This choosing to not choose builds suspense.

Also Read | Bone connection

This phone-“chimera”—the phone camera or digital camera is the modern-day instrument of what I call “obliterates”. The chimera offered by the digital while creating images is prone to a disappearance that is comparable to a “censoring” of the images. To deleting the ones that “in my opinion” do not work for me. Versus the old-fashioned analogue camera that transfers the movement into film, thereby stilling it for as long as the film lasts. The life term allotted to the invention called film negative. This mode of image-making does not allow you to tamper with that which is captured.

The light in Venice teases and tempts the photographer. Resist the lure of a Venice in colour. Except when overwhelmed by a combination of light and colour made translucent. By the very clear crisp direct Venetian light you become devoted to. Your theatre life cannot resist the clothesline hanging above your head that breaks the blue of the almost spring sky with a backlit red.

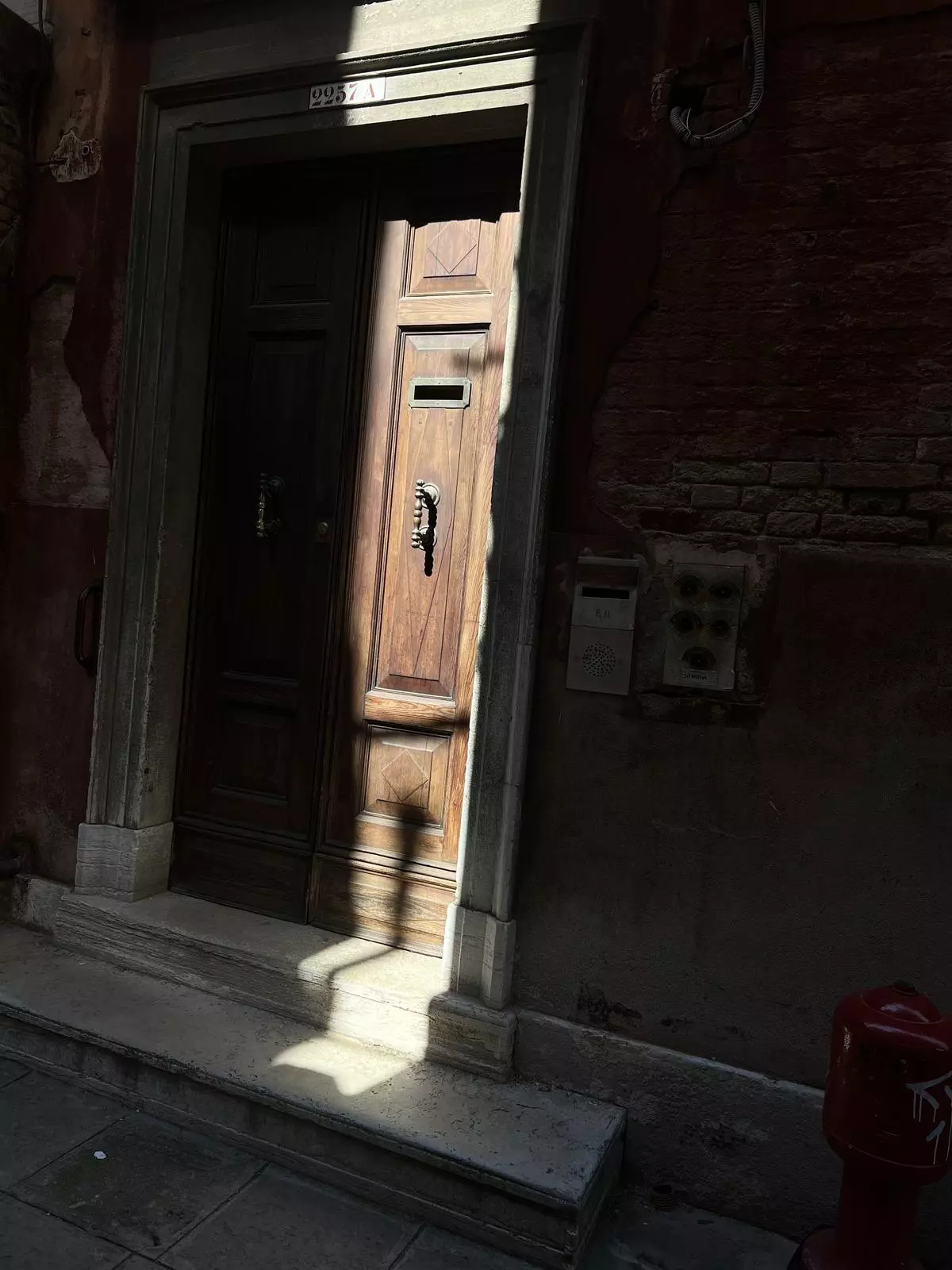

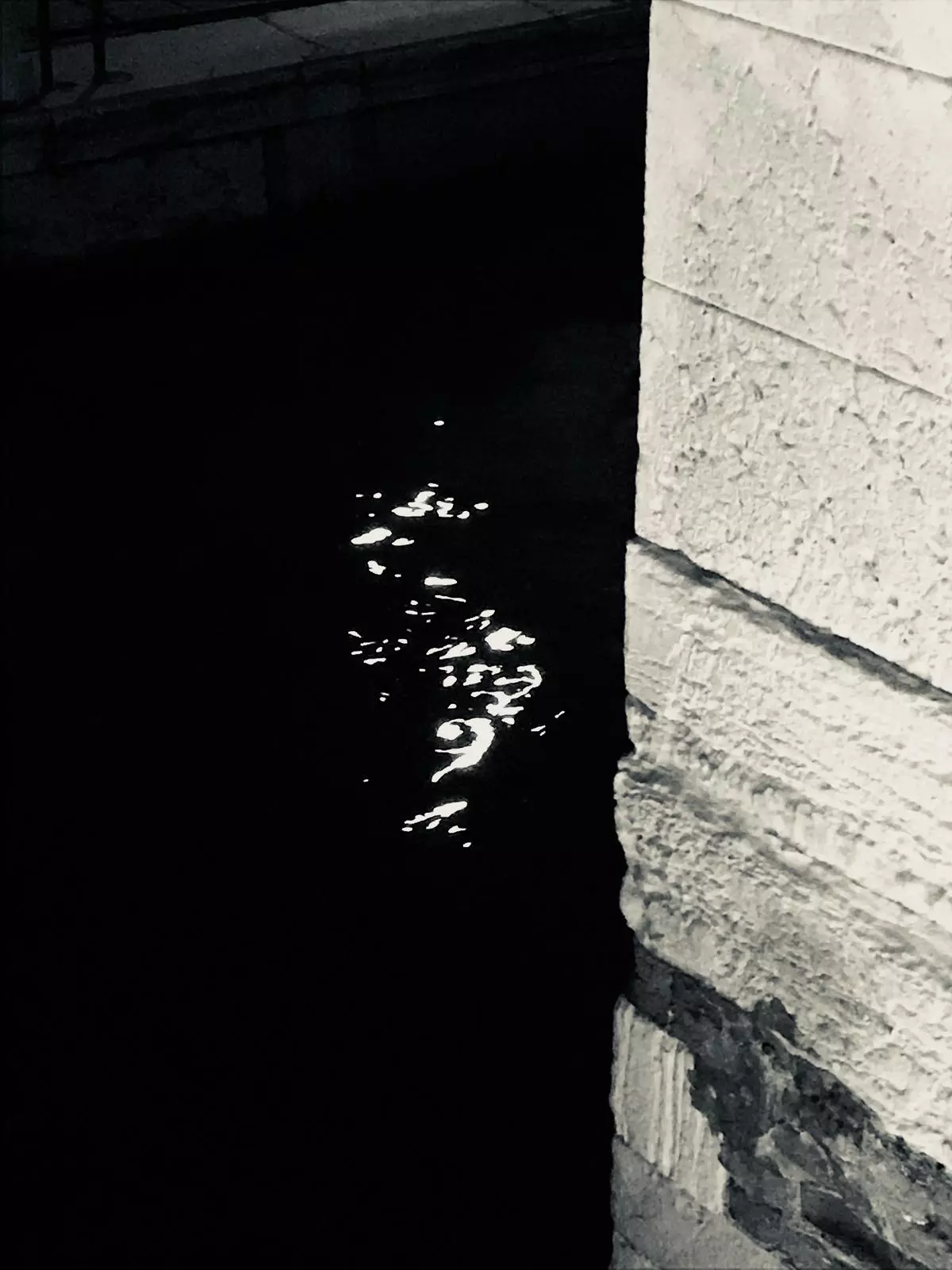

Mostly it is the black that accentuates the white in my photographs. Reflective, this light in Venice. Makes you look inwards. Even as you frame the odd gondola silhouetted against the sunlit heritage of the buildings growing out of the canals. The boatman’s shadow lengthening into the narrow canal waters with a shimmering hazy set of windows refusing to drown. Or the geometry of the black shadow squaring up like a dark pyramid on its side to the old warrior whose left knee matches the triangular tip of the shadow approaching slowly towards him at Campo S. Stae. The firstborn sliver of moon; the light upon the door knocker the size of your elbow challenging you to knock on the rosewood door.

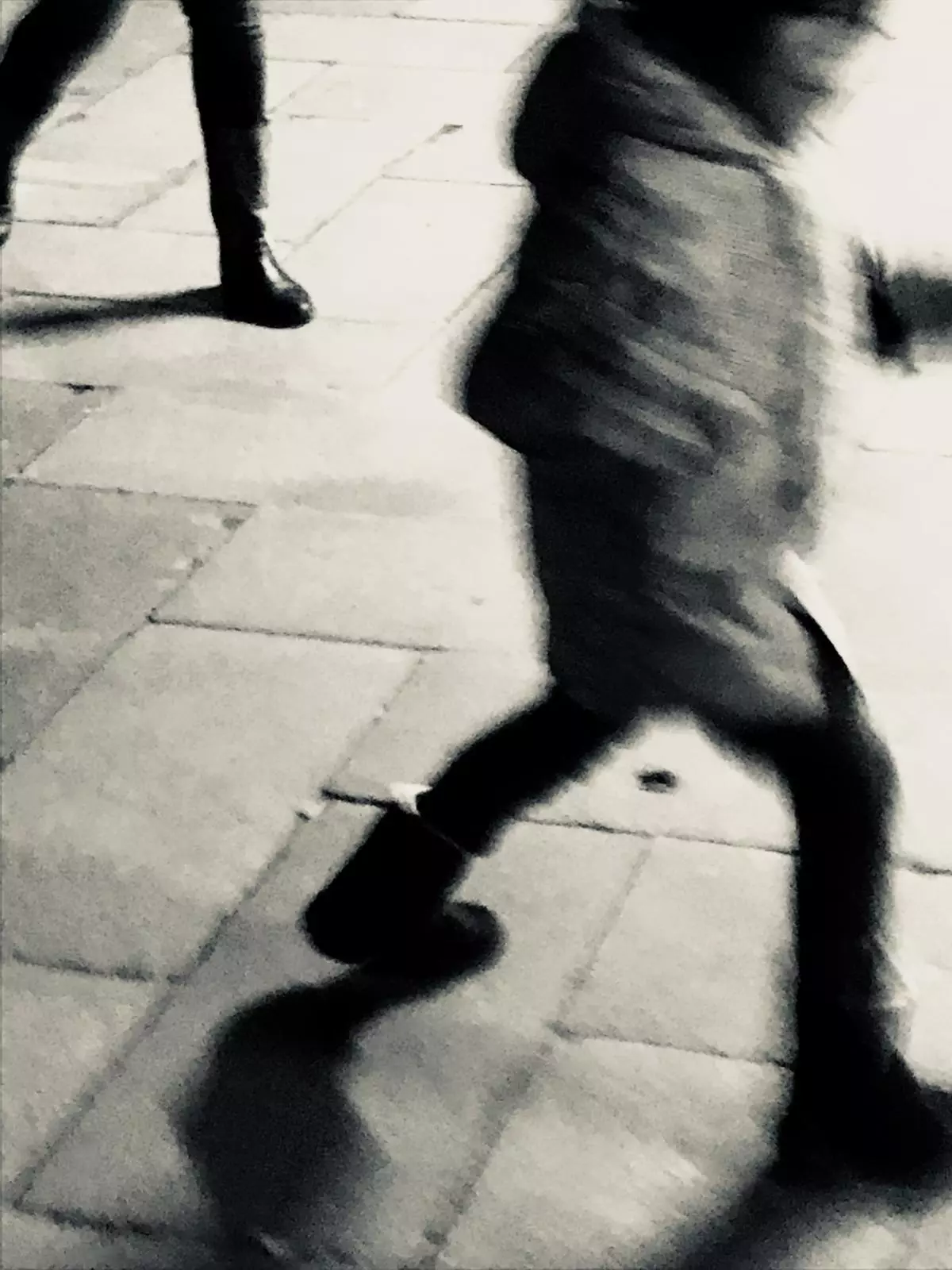

Venice changes into a silent noir film late at night. The tourists are at rest. Only the few inhabitants (they have slowly dwindled over the years) move around like so many torsos on racing feet negotiating the several tiny bridges and the shadows in the criss-crossing lanes and by-lanes that run parallel to the canals.

Also Read | Invisible lives

Naveen Kishore is a photographer, theatre lighting designer, poet, and the publisher of Seagull Books.