Support truly

independent journalism

Our mission is to deliver unbiased, fact-based reporting that holds power to account and exposes the truth.

Whether $5 or $50, every contribution counts.

Support us to deliver journalism without an agenda.

Scientists have assembled the genome of a 52,000-year-old woolly mammoth using first-of-its-kind fossil DNA fragments unearthed in Siberia, an advance that takes researchers a step closer to resurrecting the extinct giant beasts.

The study, published recently in the journal Cell, reconstructed the 3D structures of the woolly mammoth’s chromosomes, the structure in the cell nucleus in which DNA and proteins are organised into genes.

Most ancient genome specimens uncovered in fossils consist of only tiny scrambled DNA fragments.

But the 52,000-year-old fossil mammoth’s genome could be reconstructed to such detail as the animal underwent freeze-drying shortly after it died with its DNA preserved in a glass-like state.

Scientists tested dozens of mammoth DNA samples over five years to reconstruct the giant beast’s genome, before finally landing on the unusually well-preserved sample from a mammoth fossil excavated in northeastern Siberia in 2018.

This remarkable fossil retained a large amount of the chromosome’s physical integrity, including proteins in contact with the genes they control, researchers said.

With this world-first feat, scientists can better understand the mammoth’s genome organisation within its cells and learn which genes were active at different times of the beast’s life.

“This is a new type of fossil, and its scale dwarfs that of individual ancient DNA fragments—a million times more sequence,” study co-author Erez Lieberman Aiden from the Baylor College of Medicine said.

Researchers then created an ordered map of the mammoth’s genome using genomes of present-day elephants as a template.

The findings revealed that woolly mammoths had 28 chromosomes, which is the same number as present-day Asian and African elephants.

Scientists could also unravel genes likely active and inactive within the mammoth’s skin cells, revealing how the gargantuan mammal got its woolly-ness and cold tolerance.

“For the first time, we have a woolly mammoth tissue for which we know roughly which genes were switched on and which genes were off,” Marc A Marti-Renom, another author of the study, said.

“This is an extraordinary new type of data, and it’s the first measure of cell-specific gene activity of the genes in any ancient DNA sample,” Dr Marti-Renom said.

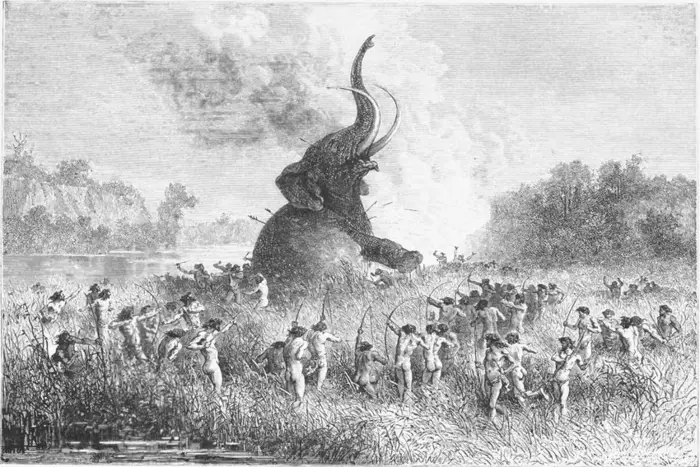

Woolly mammoths roamed the Earth’s northern hemisphere for over half a million years, and began dwindling at the end of the last ice age about 10,000 years ago.

Scientists believe a combination of factors including excessive hunting by early humans and the changing climate led to their extinction about 4,000 years ago.

“These results have obvious consequences for contemporary efforts aimed at woolly mammoth de-extinction,” M Thomas Gilbert, another of the study’s authors, said.

Researchers hope that methods used in the latest study could be used to analyse other ancient DNA specimens, including those of Egyptian mummies, to reveal their appearance and lifestyle.