We were in Bosnia for just short of a week in April this year. Our visit was primarily to see the site of the gunshot in Sarajevo that sparked the two World Wars, which defined world history in the years from 1914 to 1945. It was also to comprehend the horrendous subsequent disintegration of Yugoslavia from 1991 onwards, barely a decade after Marshal Josip Broz Tito’s death in 1980, a disintegration that, particularly after 1992, increasingly took the form of genocidal internal strife in which the main—but by no means the only—ones to suffer were the Muslim majority of Bosnia-Herzegovina.

The morning after we got into Sarajevo, our first port of call was Franz Joseph Street (now Ulitca Zenicni Beretki), where Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife, Countess Sophie, were assassinated on June 28, 1914, by Gavrilo Princip. The street is dominated 110 years later by a sign in English proclaiming, “BEWARE: Thieves and Pickpockets”. It struck me that in 1914 it should have read, “BEWARE: Assassins”!

The origins of the First World War are generally regarded as having no relevance to India-Pakistan relations more than a hundred years later. But it seems to me that nothing better illustrates the dangerous edge on which India-Pakistan relations totter as the background to the Sarajevo assassination and its wholly unanticipated worldwide consequences that led to an estimated 100 million deaths and serious injuries in the two World Wars that followed.

Also Read | From war to Cold War

In his The Fall of Dynasties (1963), Edmond Taylor writes: “All convulsions of the last half-century stem back to Sarajevo: the two World Wars, the Bolshevik revolution, the rise and fall of Hitler, and the ongoing turmoil in the Middle East.” So, here goes.

First World War origins

The story begins on June 13, 1903, when 28 officers of the Serbian army brutally killed their King, Alexander, and his consort, Queen Draga. The principal instigator of this coup was Lieutenant Dragutin Dimitrijevic, more generally known by his nickname “Apis” because of his heavy-set resemblance to the Egyptian bull god of the same name.1

Apis’ strong, indeed extremist views rendered him an ultra-nationalist Serb harbouring grandiose ambitions for the establishment of a Greater Serbia covering all South Slavonic lands. While the mainstream establishment under Prime Minister Nikola Pasic was wary of such over-the-top goals, elements in the administration, and more in the army, were much impressed with Apis.

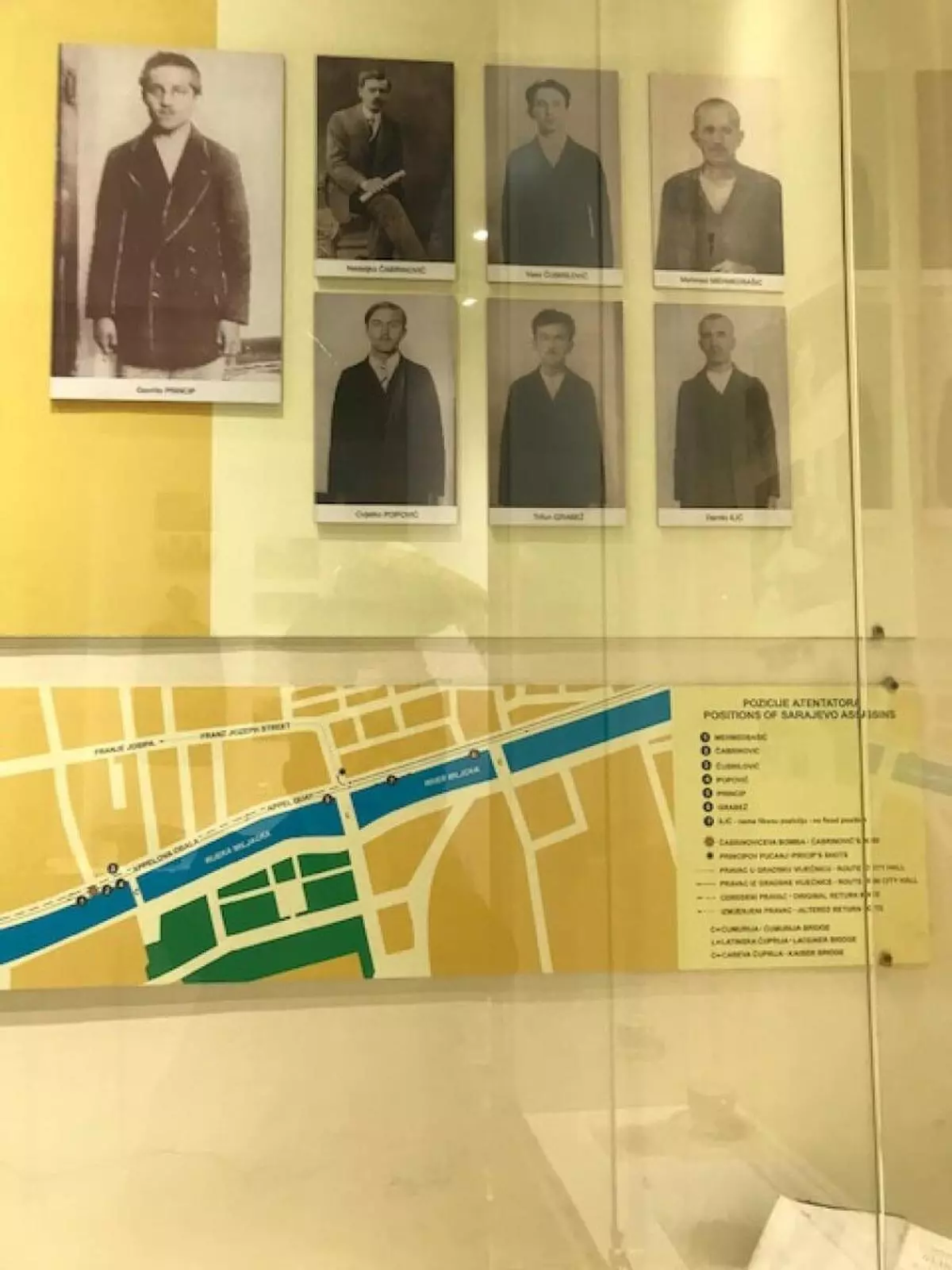

At a museum in Sarajevo, portraits of the seven conspirators who plotted to assassinate Archduke Franz Ferdinand, and a map of the route taken by his convoy.

| Photo Credit:

MANI SHANKAR AIYAR

Consequently, Apis rose to become Head of Military Intelligence, and as an offstage private enterprise, he founded and nurtured a secret terrorist organisation called Union or Death (Ujedinjenje ili Smrt), which, like its founder, was better known by its nickname, Black Hand (Crna Ruka). The parallel to the Hizbul Mujahideen and Lt Gen. Hamid Gul, chief of Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence, begins here.

Black Hand’s agents recruited young men in their teens who were almost all extremely poor and usually suffering life-threatening ailments such as tuberculosis but were fired with the desire, or shall we say driven by the psychological need, to make something of their short, deprived lives by ending it in a blaze of patriotic glory: martyrdom (shahadat, as the Pakistanis say). Just as with many of the recruits to the Hizbul Mujahideen, the Lashkar-e-Toiba, and the Tehreek-i-Taliban Pakistan.

Black Hand

Black Hand’s methods and objective were made clear in the insignia they adopted: “a circular logo bearing a skull, crossbones, a knife and a vial of poison and a bomb” (Christopher Clark, The Sleepwalkers, Allen Lane, 2012). Within six months of the formation of Black Hand, the three Balkan wars of 1912-13 had broken out, led on the Serbian side not only by the regular army but also by vicious vigilantes armed and financed by rogue elements in the Serbian establishment, even if not approved by the Pasic government—again much like the terrorist groups based in Pakistan.

However, as Clark says, “the Serbian government showed no interest whatsoever in preventing further outrages or in instigating (sic) an investigation of those that had already occurred” (pages 44-45). Very much like the Pakistan government.

Nevertheless, tension between the army and the civilian government had so mounted by May 1914, the very month in which Princip and his terrorist cohort infiltrated Bosnia, that Apis “retired from the fray” to concentrate exclusively on the terror organisation he had created to realise his excessively supra-nationalist goals.

Parallels with Pakistan

There are strong parallels between these events and the terrorist outfits in Pakistan. The terrorist organisations are not officially legitimised, but even as the civil wing distances itself from their activities, rogue elements in the army do their utmost to help (shades of “Major Iqbal” of 26/11 notoriety).

As the historian Clark remarks, “[t]here was a paradoxically public quality to the clandestinity of the Black Hand” as “the government and the press were aware of the movement’s existence”. So also with the anti-India terrorist groups: everyone in Pakistan knows what they are up to, but the government remains in hapless denial or indifference!

And even as the Pasic government in Belgrade “viewed the Black Hand as a movement to overthrow the Serbian state from within” (page 41) but did precious little to rein it in, so too the Pakistan government has shown itself pretty impotent in liquidating the Tehreek-i-Taliban Pakistan, which seeks to overthrow the present system in Pakistan and bring in a model based on the Taliban in Afghanistan.

Three members of Black Hand’s assassination squad infiltrated Bosnia from Serbia and met up with four others who were already in Bosnia. Under the overall leadership of Danilo Ilic, five were stationed beside a series of lamp posts that marks the embankment of the Appel Quay (now known as Obala Kulina Bana), which runs along the Miljacka river, neatly dividing the city into right and left banks. The lamp posts are still there, and I stood at the side of each of them to relive the memory of the assassination.

The Archduke’s assassination

The Archduke’s route was known to all because people had been gathered to shout slogans and welcome the Archduke and his party. The first assassin, Mohammed Mehmetbasic, the only Muslim and, at 28, the oldest of the gang, was stationed beside the first lamp post the Archduke’s open car would pass after crossing the Cumurija (Democracy) bridge over the river. His nerve broke even as he freed his bomb from its swaddling because he sensed a policeman to his immediate rear. He failed to throw the bomb.

The next in line was 19-year-old Nedeljko Cabrinovic, who threw his bomb, but the Archduke’s chauffeur saw it coming and accelerated. The bomb thus fell under the wheels of the next car and exploded, injuring two of the Archduke’s aides, one seriously, and several bystanders. For his part, the would-be assassin swallowed cyanide and fell 26 feet down the riverbank, but as the cyanide was of inferior quality, it merely burnt his throat and damaged his stomach lining, and he was captured alive.

At the museum, a somewhat fanciful plaster-of-paris representation of the Archduke and Archduchess exiting City Hall before their “tryst with destiny” on that fateful day.

| Photo Credit:

MANI SHANKAR AIYAR

Vaso Cubrilovic, next in line, had not realised that the Archduke’s wife would be accompanying him and so, on seeing her, courteously decided not to pull out his revolver. The fourth, Popovic, lost courage at the last minute and instead of throwing his bomb, he raced across to a Serbian cultural centre and stored his bomb there. The fifth, Grabez, left his post, probably out of fear, and got so mixed up in the crowd that when the time came, he was too much in the thick of it to safely throw his bomb.

So, the Archduke escaped, almost without knowing it, from as many as five planned assassinations. He was understandably very upset and vented his spleen at the City Hall (Vijecnica) where the Mayor, Effendi Curcic, had arranged a civic reception with all of Sarajevo’s dignitaries present. What particularly upset the Archduke was that he had scheduled this visit for one major reason: it was his 14th wedding anniversary.

His had been a morganatic marriage (one where none of his offspring could succeed him as Emperor) because court protocol decreed that the Hungarian Countess, Sophie Chotek, was not sufficiently blue-blooded to become Empress. So, she was excluded from all court engagements in Vienna. But, as formalities to fully incorporate Bosnia into the Austro-Hungarian Empire were still not complete, she was privileged to be at her husband’s side, with all due honours, when he went to Bosnia-Herzegovina in his capacity as Commander-in-Chief of the Bosnian army.

In his First World War (Penguin, 1963), A.J.P. Taylor writes that although Franz Ferdinand was brutal, cantankerous, obstinate, and impatient, “he had one redeeming feature: he loved his wife”. Thus, the bloodiest wars known to history were not sparked by hatred but by deep love!

Gavrilo Princip strikes

After City Hall, the party was supposed to travel down Franz Joseph Street, where the last of the assassins, a despairing Gavrilo Princip, was, in typically Balkan fashion, drowning his sorrows in coffee while munching a sandwich. Meanwhile, the Archduke insisted on going to the hospital to see the injured aides. However, someone forgot to brief the chauffeurs. So, the Archduke’s driver turned right from Appel Quay into Franz Joseph Street when Governor Potiorek shouted at him to reverse and drive straight along the quay to the hospital.

Also Read | 1961: First NAM summit in Belgrade

But the car did not have a reverse gear; it had to be pushed to retreat. Princip looked up to see the target of his assassination parked right in front of him. Without hesitation, he leaped onto the running board of the car and fired with his pistol at the couple. Sophie died within minutes of the attack and the Archduke a little later. His last words to his wife were: “Sophie, Sophie don’t die, stay alive for our children.” Princip was immediately overpowered and taken into custody, without being able to swallow his suicide powder.

Within days, all seven conspirators were rounded up and jailed before being put on trial. Most could not be hanged or shot because under Austrian law only those above the age of 21 could be executed. Ilic, the senior coordinator, was thus the only one to be hanged. Both Princip and Cabrinovic, the one who fired the fatal shots and the one who threw the bomb that missed its target, were sentenced to 20 years of hard labour. Both died in jail of overwork, undernutrition, and consumptive illness before the First World War ended. So did Grabez. Mehmetbasic survived the First World War but was killed by the Ustase, the pro-Nazi extremist fascist Croatian underground, during the Second World War. Popovic survived and died a natural death in 1980 at the ripe old age of 84.

The last of the assassination squad, Vaso Cubrilovic, was sentenced to 16 years of hard labour but was released at the end of the First World War. He went on to become a renowned academic and lived the longest, dying of natural causes in 1990 aged 93. Apis, the head of the Black Hand, was executed for high treason before the First World War ended.

A century later

And what of the site of the assassination? More than a century later, the coffee house where Princip sat is raking it in from passing tourists under its new name, “Sophie’s Garden”, named after the Archduchess. A plaque on the wall announces in English that it was “From this place” that Princip “assassinated the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne” and “his wife, Sofie”.

Right next to the plaque is the entry into a museum that displays a model of the two descending the steps of City Hall on their way to their tryst with destiny, photographs of the assassination squad, their clothes, the pistol that Princip used, and other memorabilia.

I seated my wife, Suneet, on a chair on the pavement outside the café to take a photograph of the very spot at which the one successful assassin might have sipped his coffee.

Although Emperor Franz Joseph was curiously indifferent to the assassination of his heir (his brother’s son, since his own sons had both died), whom he did not much like personally, others in the Austro-Hungarian establishment, particularly the Austrian army chief, Conrad von Hotzendorf, saw in the assassination a golden opportunity to wreak vengeance on Serbia: “If you have a poisonous adder at your heel, you stamp on its head, you don’t wait for the deadly bite,” he said.

At the National Theatre in Pristina, Kosovo, on July 11, where people gathered to mark the 29th anniversary of the 1995 Srebrenica genocide.

| Photo Credit:

ARMEND NIMANI/AFP

In this, he was heavily backed by the German Kaiser, Wilhelm II, who, quite irresponsibly, urged the Austrian government to take on the pesky Serbs, fully convinced, without any definitive proof, that the official Serb government under Nikola Pasic must have been behind the nefarious assassination and that this was an unmissable opening to show the Serbs their place. For his part, much like the Pakistanis, Pasic protested his government’s innocence—no proof was ever found that the government was involved in Apis’ activities—and promised to undertake a thorough inquiry into who was behind the assassinations. But the Austrian Emperor, in a letter to the German Kaiser drafted by his officials, stressed that “after the recent terrible events in Bosnia there can be no further question of bridging by conciliation the difference that separates Serbia from us”.

Can you hear Prime Minister Narendra Modi growling a century later that after the “terrible events” in Pathankot, Uri, and Pulwama, there can be no conciliation between Pakistan and us?

Austria and Serbia

Short of “bridging the differences” between Serbia and Austria through intensive dialogue, the Austrian establishment believed that the only way open to exact revenge for the heinous crime of the heir’s assassination was the invasion of Serbia. It was imagined by the Austrian army chief that, given the huge asymmetry between the armed forces of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and those of Serbia, the 1914 equivalent of what the Modi government now terms “a surgical strike”, was all that would be required to teach the Serbs a lesson.

So, the Austrians drafted a multipoint ultimatum, which they spent a lot of time polishing up because they wanted Serbia to reject it and thus give themselves the excuse to attack and subdue Serbia.

One is reminded of the description in C.R. Gharekhan’s Centres of Power (pages 44-53) of how, as the division chief for Pakistan in the Ministry of External Affairs in 1982, he was witness to all the big names in Indira Gandhi’s circle of power—P.C. Alexander, G. Parthasarathi, K. Natwar Singh, Foreign Secretary Ram Sathe and his successor, M. Rasgotra, and, indeed, he himself, presided over magisterially by External Affairs Minister P.V. Narasimha Rao—competed with each other to prepare a draft treaty that Pakistan would have to reject: “Our idea was to present the Pakistanis with a draft which they would find extremely difficult to accept…. The talks ended in a stalemate…. That meant our mission was successful!”

Also Read | The arrest of Milosevic

The Serbian document was labelled by Winston Churchill in a letter to his wife as “the most insolent document of its kind ever devised” (Clark, page 456). Yet, the Pasic government in Belgrade accepted—albeit conditionally—most of the demands, rejecting only two that impinged on its sovereignty: one, that Austria be involved in the investigation; two, the establishment of a mixed Austro-Serb commission of inquiry.

One expects Pakistan would similarly reject any demand for the involvement of India in any investigation or adjudication of the terrorist atrocities committed by Pakistan-based terrorist organisations in India, although the joint Anti-Terrorist Mechanism devised by Manmohan Singh and Gen. Pervez Musharraf in Havana in 2007 might offer a way out.

Entry of Russia

What the bellicose Austrians had apparently not adequately taken into consideration was that the mighty Russian Empire would not sit on its hands while a fellow-Slav state, almost a client state of the Russians, was attacked by its powerful central European rival, the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

The parallel to China coming to the aid of its client state, Pakistan, in any future conflict with India, especially as China would not now require, as in 1965 and 1971, the crossing of the Himalaya but a coordinated counter-attack with Pakistan across the Indus river, is a consideration that our leaders, civil and military, would be well advised to take into consideration.

At the last moment, the Kaiser awoke to the reality that an attack by Serbia on Belgrade backed by Germany would inevitably result in war breaking out between Germany and his two neighbours, Russia to the north and France to the west (our potential adversaries are also to the north and west).

He tried to stop the dogs of war from being unleashed, but the Austrians would have none of it. The renowned Canadian historian Margaret MacMillan sees in the weaker Austria dragooning the much stronger Germany into “dangerous policies” that eventually led to the annihilation of both empires a parallel to the US being similarly dragooned “by Israel or Pakistan today” into actions detrimental to the larger US interest.2

Gravestones at the Potocari genocide memorial near Srebrenica.

| Photo Credit:

MICHAEL BUKER/WIKIPEDIA

So, Russia came into the war as soon as Austria entered Serbia, opening for Germany a two-front war that Germany had always dreaded but brought upon itself by putting into motion the secret Schlieffen Plan that envisaged the entry of German troops into Paris by the 39th day of the war, with, as Field Marshall Alfred von Schlieffen colourfully put it, “the last man on the right brushing the Channel with his sleeve”.

This, of course, meant the violation of Belgium’s neutrality, the most important plank, it was believed in London, of England’s national security. Both the French Republic and the Czarist Empire invoked their solemn pact to come to each other’s aid if either was attacked, and a hitherto reluctant England was left with no alternative by Germany’s violation of Belgium’s neutrality but to send in a British Expeditionary Force (BEF) to assist the French.

At about the same time, the Ottoman Empire decided that Czarist Russia would push to Constantinople (Istanbul) to force its way into the Mediterranean and, therefore, allied itself with Germany. And Britain brought the Japanese Empire into the Alliance, thus converting a European civil war into the First World War.

War breaks out

And so it came about that “some damn thing or the other” in the Balkans, as Lord Palmerston, Britain’s long-serving Foreign Secretary, later Prime Minister, had predicted decades earlier, converted a distant quarrel in the South Slav lands into the spark that ignited two world wars, brought down five centuries-old empires, and, after the Second World War, the British and French Empires as well, thus inaugurating the post-1945 Pax Americana to counter the Cold War with the Soviet Union, which in turn led to literally over a hundred armed conflicts in proxy wars around the world, notably in Korea, Indochina, West Asia, the Congo, and many parts of Africa.

Worldwide casualties exceeded 100 million. Such were the unforeseen global ramifications of the assassination. It was an outcome that no statesman or military chief had anticipated in that somnolent summer of 1914. Most of the leaders of Austria, Germany, Britain, France, and even Russia were holidaying in the month after the assassination, so far away and so irrelevant to their quotidian lives seemed the assassination in Sarajevo.

Yet, by August 1914, when everyone should have been at the seaside, Europe was convulsed in one world war followed by another that heralded the death of the brightest flowers of French, Russian, Austrian, and Yugoslav youth, and most of the experienced officer corps and soldiers of the United Kingdom in the BEF, in just the first 30 days of the four-year-long First World War, brilliantly encapsulated in Barbara Tuchman’s The Guns of August; she estimates the French toll in August 1914 alone at 3,00,000, which included all the 1914 graduates, bar one, of St Cyr, the prestigious French military academy (footnote on page 439).

What we need to guard against in South Asia is a similar unanticipated tragedy suddenly overwhelming the region, bristling with nuclear weapons. We have to engage with Pakistan and China, virtually its ally, so that “some damn thing or the other” does not suddenly plunge us into a fiery hell. Much more than even the Great Powers of the first half of the 20th century, India and Pakistan and China, as responsible nuclear weapon powers, need to at least endeavour to “bridge their differences”.

Yugoslavia disintegration

In an eerie intimation of what was to happen in the mid-1990s, the British Consul during the Balkan wars nearly a century later reported that “under Servian rule, the Moslems have nothing whatsoever to expect but periodical massacre, certain exploitation and final ruin…. Moslem populations are in danger of extermination by the very frequent and barbarous massacres and pillage to which they are subjected by Servian bands” (Clark, page 44).

Exactly as predicted, this happened when Yugoslavia disintegrated after Marshal Josip Broz Tito, the great unifier of Yugoslavia, died in 1980. Pressures to split the country into its constituent ethnic parts started intensifying, not unaided by their mainstream European partners, Austria for Slovenia which seceded in 1991, followed by Croatia patronised by Germany (some said for services rendered by the Croats to the Nazis in the Second World War).

Bosnia-Herzegovina’s turn to work for secession and independence came immediately thereafter but was hideously complicated by Bosnia being home not only to the majority Bosniaks (that is, Bosnian Muslims), whose conversion dated back to Ottoman rule, but also home, in substantial numbers, to Orthodox Serbs and Catholic Croats.

It is estimated that the shares in the population were Muslims 44 per cent, Serbs 31 per cent, and Croats 17 per cent. Moreover, to the west, Bosnia-Herzegovina was hedged in by the Dalmatian coastline of Croatia and to the south by Montenegrins, who regarded themselves as Serbs. Fleeing east or north was out of the question as there lay Serbia. The hostile neighbours regarded heterogenous Bosnia as the principal impediment to their dreams of a Greater Serbia and a Greater Croatia, which they hoped to attain by dividing and incorporating Bosnia-Herzegovina into their respective territories.

Inhuman violence

To understand this frightful outbreak of inhuman violence, so reminiscent of our own Partition, we travelled south from Sarajevo to the incredibly lovely medieval town of Mostar, which came under attack from non-Muslim Bosniaks, Croats, and Montenegrins in the mid-1990s. Artillery fire was directed at the arched stone bridge over the turquoise blue waters of the Neretva river, a symbol of half a millennium of Turkish rule from the 15th century to the beginning of the 20th century. The bridge collapsed into the river (since rebuilt by UNESCO). Hideous massacres followed as Croats and Serbs occupied Mostar.

The scars of that ghastly period were revealed in every conversation we had with local people. Shaking her head in disbelief, one young Bosniak woman told us that 40 per cent of all marriages in Mostar before the troubles were interfaith marriages between Muslims and Catholics. “Religion,” she said, “did not matter.”

The holocaust lives on in Mostar’s Muslim minds, for, to get into the medieval town’s maze of twisting byways, we had to cross a busy main road that even in 2024 marks the divide between the Croatian and Muslim habitations of the town.

For Mostar’s inhabitants, life must be like living at the Attari-Wagah crossing, so divided that only one school takes in both Croat and Muslim children. Yet, despite the thousands of tourists who now visit Mostar, wonder-struck by the beauty of the place and the numerous eateries and restaurants serving excellent food and drink, for the local people, the place is still haunted by memories of the heartless butchery.

But Mostar alone was not the target. We, therefore, took the bus back to Sarajevo and then through the winding roads of verdant mountains to Srebrenica, site of the worst genocidal massacre of Bosniak Muslims over the three ghastly years of 1992-95.

We were not quite out of Sarajevo when a curious sign caught my eye, a large hoarding announcing that we were entering “The Autonomous Republic of Srpska”. I looked it up on Google to find that the hoarding related to the conclusion through the 1995 Dayton Accords that ended the fratricidal war of the mid-1990s between the Bosniaks, the Bosnian Croats, and the Bosnian Serbs. Under the Dayton Accords, Bosnia-Herzegovina was preserved as a single state with its common capital in Sarajevo but federated into a Bosnian-Croatian federation, on the one hand, and conjoined, on the other, to a Bosnian Serb republic known as the Autonomous Republic of Srpska (pronounced “sripska”).

Ethnic cleansing of Muslims

On Bosnia’s declaration of independence in March 1992, followed by international recognition and its admittance to the UN, local Serbs, heavily supported with arms, ammunition, finance, and armed forces personnel from neighbouring Serbia, formed the Army of Republika Srpska (HVO). Under the command of Ratko Mladic, they surrounded Sarajevo and other Muslim-majority towns and cities, such as Mostar, and initiated a brutal campaign of “ethnic cleansing” that resulted in the destruction of approximately 296 Bosniak villages in the mountainous north-east and north-west regions, the displacement of around 70,000 Muslims, and the massacre of over 3,000 Bosniaks, including women, children, and the elderly.

“Hideous massacres followed as Croats and Serbs occupied Mostar. The scars of that ghastly period were revealed in every conversation we had with local people. ”

Many fled to the UN-declared “safe zone” centred on Srebrenica, a small habitation of some 5,000 souls, which swelled to nearly 50,000 through the arrival of Bosniak refugees. The HVO was taken on by a Bosniak Army of Bosnia and Herzegovina (known by its initials, ARBiH), led by the charismatic Naser Oric. Atrocities were committed by both belligerents, but the Serbs outdid the Bosniaks in genocide and war crimes, especially on three awful days of July 11, 12, and 13 when they undertook a genocide of 8,712 innocent unarmed Muslim men and boys and forced out 23,000 Muslim women and girls, many of whom were raped and abused.

The most poignant story we heard at the Potocari memorial, just outside Srebrenica, was of a girl child being raped repeatedly by Serb soldiers with her mother wiping the blood flowing down the legs of the girl and begging, “Please let her be. She is only nine years old.”

Another shocker was a video clip of a man being forced by the Serb forces in the valley to call out to his boys to come down from the mountains as the Serbs had promised they would be safe. The boys responded, but when they came down, all three were mercilessly shot dead.

There were other stories we were told of civilians being rounded up and herded into schoolrooms, which were then raked with gunfire until all of them were dead and those who escaped were killed with a single shot to their heads. Just one escaped by pretending to be killed and then made his way through an open window to tell his horror story, since verified, to the world.

Hundreds of such tales were assiduously collected and checked by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. The International Court of Justice at The Hague continues its decades-old hearings into charges of genocide and war crimes, many of which are concluding with convictions, although some of the worst offenders, including Serb President Slobodan Milosevic, died before a sentence could be pronounced.

The HVO army commander, Ratko Mladic, is serving a life sentence.

Srebrenica, a ghost town

Srebrenica is now a ghost town. Even the bus stand is boarded up. The ones who remain are mostly widows who survived the ghastly crimes of mid-1995. Young people, unable to find employment, have migrated to nearby towns or to Sarajevo and abroad. The town’s leftover residents live on their children’s remittances as there is virtually no employment. There are few restaurants, cafés, or coffee shops, but there is one supermarket where the few who remain buy their supplies. With no hotels, most visitors stay in nearby towns like Brunac and Tuzla. We found a small, clean, and well-stocked Airbnb looked after by Abdullah, in his 60s, who went out of his way to drive us around and attend to us like a mother hen.

Also Read | Bosnian Serbs threaten to block country’s major institutions

Those who remain in Srebrenica tend to their gardens and their flowerbeds; the streets are clean and well-swept; the houses neat; and the surroundings breathtakingly beautiful. But hanging over the town is a pall of distress. We left it with sorrow and, as Indians who went through Partition, a measure of sympathy, indeed, empathy.

We took back to India the confirmation that Yugoslavia, like India, was a magnificent exemplar of unity in diversity, forged from a multitude of ethnic identities, many languages and dialects, many religions.

To an Indian, this seems natural; to Europeans, constricted by equating ethnicity with nationhood, it seemed a monstrous artificial construct.3 They were, therefore, complicit in dismantling it.

There is no greater danger to India’s nationhood than the imposition of the European equating of nationhood with ethnicity, taken to an extreme by the Nazis who so impressed V.D. Savarkar and his fellow-champions of Hindutva. In standing up for multi-ethnicity in former Yugoslavia and, indeed, for multi-ethnicity in contemporary Bosnia-Herzegovina, we would be standing up for the Indian concept of nationhood. Short of that, we, as a nation, run the risk of becoming another former Yugoslavia. Therefore, our people need to know Bosnia better.

Mani Shankar Aiyar is a politician and former diplomat.

- Sometimes “Apis” is translated as “bee”, as in Niall Ferguson (2006): The War of the World, Allen Lane, page 77, from which it follows that the ultra-nationalist terrorist organisation Apis founded was akin to a beehive.

- Macmillan, Margaret (2013): The War that Ended Peace, New York: Random House.

- This point was elaborated in my 2004 publication, Confessions of a Secular Fundamentalist, New Delhi: Penguin/Viking, pp. 234-239.