Support truly

independent journalism

Our mission is to deliver unbiased, fact-based reporting that holds power to account and exposes the truth.

Whether $5 or $50, every contribution counts.

Support us to deliver journalism without an agenda.

There was no warning before the earthquake in Lisbon on Monday morning last week. Worse, the computer system of Portugal’s oceanic and atmospheric agency crashed shortly after the shaking began at 5.11am. No injuries have been reported, but residents, who were mostly fast asleep when it hit, have told of being terrified, jumping out of bed and “not being able to stand up”.

Patricia Brito, who lives in the centre of the city, says that, once she found her footing, she skidded into her parents thinking “this was the big one”. The shaking lasted less than a minute, but for three hours she couldn’t go to sleep as she and her friends WhatsApped each other from Setubal to Porto as they shared their stories. “One friend woke up and threw up a minute before it started, so she must have been hyper-sensitive to it coming.”

While the earthquake was moderate, with Lisbon 84km from its epicentre, the news dominated Portuguese and European headlines as it was felt in Gibraltar, Spain and Morocco.

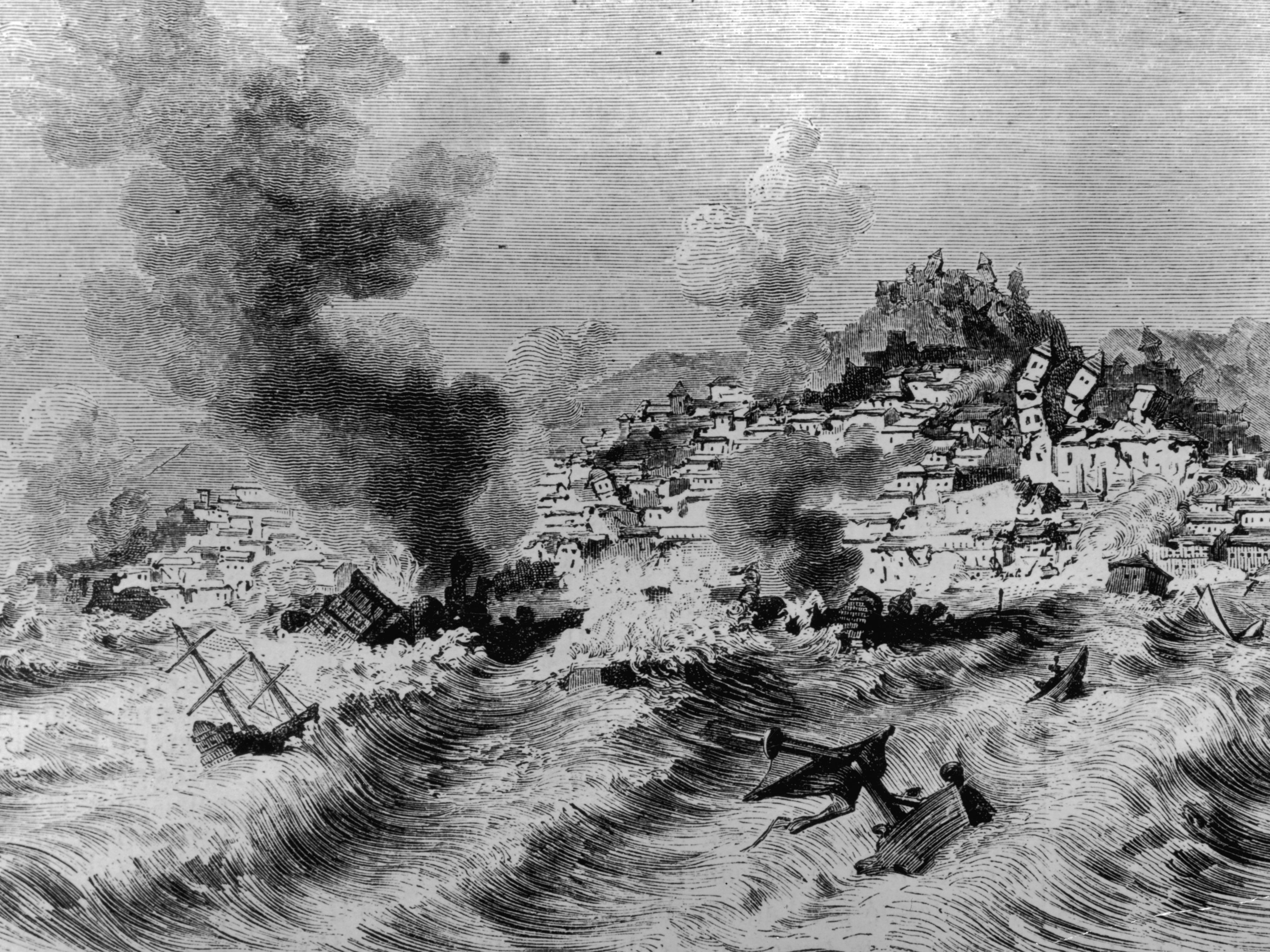

The panic among Lisboetas was also understandable as residents of the city are used to living in the shadow of 1755, when a massive earthquake collapsed Lisbon’s churches during mass, launched tsunami waves over the city’s walls, and caused fires that lasted six days.

Scientists estimate the magnitude of that devastating event was 7.7 compared to the 5.4 that occurred on 26 August. What would an earthquake of that size mean for Lisbon today?

Given that two-thirds of the city’s buildings were built before anti-seismic regulations of the 1980s, the damage could be untold, which is why residents of that city are often exposed to drills whether that is tsunami alarms that are tested near the waterfront of the city, or school children being given instructions of what to do in the event of a catastrophic event.

Even last week, residents were all sent text messages reminding them to be alert to aftershocks, keep shoes close to them and check for cracks, damage and smells of gas.

We might not want to think about it, but Lisbon, like many holiday destinations, is under constant threat. It is just a matter of time before another big one strikes southern Europe. There’s no stopping the African tectonic plate on its path northward, threatening major upheaval.

Research published this May indicates that the climate crisis has magnified the hazard: rising sea levels and stronger storms can trigger earthquakes and related disasters like landslides and tsunamis. Even a little extra pressure from a full lake or reservoir can initiate seismic slip. This means increased risk for coastal areas around the Mediterranean, which are particularly vulnerable.

Not even the UK is safe, where earthquakes might seem exotic from the vantage point of the British Isles. In the 19th century, the popular historian Henry Thomas Buckle insisted that freedom from earthquakes was a precondition for Britain’s economic dynamism, since fear would discourage investment.

He even claimed that earthquake-prone lands were doomed to mental backwardness, for “there grow up among the people those feelings of awe, and of helplessness, on which all superstition is based”.

Nonetheless, the Scottish highlands have a long, well-documented history of small earthquakes. The tiny village of Comrie even became a tourist destination in the 19th century for those curious to feel the earth shake. In 1863, a tremor was palpable across 85,000 square metres of England, and in 1884 a quake centred in Essex caused enough damage to launch a national collection.

For a brief moment following these tremors, fear struck the heart of the British empire. Charles Dickens proclaimed that “we enjoy no immunity from the most sudden, the most irresistible, the most destructive of nature‘s powers. Another such shock as the Lisbon earthquake may happen this or next year.”

The Times warned of “means, utterly beyond our ken and our computation, far below our feet, by which cities may be subverted, populations suddenly cut off, and empires ruined…Who can say what strange trial of shaking, or upheaving, sinking, dividing, or drying up may await us?”

These were passing worries. Earthquakes in the UK were sooner entertainment than hazard. Nineteenth-century Londoners could procure a thrill by visiting the Cyclorama’s recreation of the Great Lisbon Earthquake, including moving scenery and offstage screams.

British earthquakes were long forgotten when the UK began building nuclear reactors in the 1960s, without anti-seismic reinforcement. Seismologists did their best to raise awareness. In 1983, The New Scientist placed an image on its cover of a cup of tea being thrown from its saucer, with the headline “Is Britain Prepared for Earthquakes?” The Times responded with a dismissive editorial, insisting that the British “have other things on their mind”.

In the 2010s, reports of tremors in Lancashire were linked to hydraulic fracking, which can trigger earthquakes much as rising water levels do. The government placed a moratorium on fracking in 2019, but fear of a fuel shortage from the war in Ukraine has driven demands to lift it. Experts are still calculating the risks.

The earthquakes that threaten southern Europe are roughly 100,000 times more powerful than the ones produced by fracking in the UK. Governments in the region rely on short-term forecasting to avert disaster.

Following a deadly earthquake in L’Aquila, Italy in 2009, six seismologists were convicted of manslaughter because they had failed to warn the city of imminent danger.

Although their convictions were overturned on appeal, the demand for earthquake forecasts has grown. This is a dangerous trend, since seismologists agree that there’s no reliable method for predicting earthquakes.

The only way to reduce risk is to avoid building near active faults and to enforce construction codes. The message is clear: facing up to seismic risk requires long-term planning.

It also requires cooperation. The most destructive earthquake in Europe’s history hit Sicily in 1908. It killed approximately half the residents of Messina and destroyed around 90 per cent of the city’s buildings.

The disaster struck as Europe’s imperial powers seemed headed towards conflict. Just two months earlier, Austria had annexed Bosnia, fanning the flames that would lead to war in 1914.

The humanitarian response to the earthquake was prompt and dramatic. Dozens of Russian, British, French, and American ships brought food, blankets, and construction materials. American workers built roughly 3,000 new homes for the survivors with material provided by the US government and the Red Cross.

They did so with the explicit aim of promoting “good feeling between the nations”. Two weeks after the disaster, the cover of a German satirical magazine featured a drawing of two demons, one commenting to the other: “Everything was so beautifully prepared for a war. Then that meathead comes and makes an earthquake! The whole human race is fraternising again, and we’ve lost our chance.”

Although the demon was sadly mistaken about the chance of war, the earthquake did inspire international partnership in the long term.

The International Relief Union was founded in 1927 by a member of the Italian Red Cross who had dedicated several months to recovery work in Messina in 1908. There he learned that responding to disasters would require an unprecedented degree of international coordination.

Earthquake preparedness also calls for cooperation with the public. One of the surest ways to collect information about seismic risk while raising public awareness is to encourage citizens to take science into their own hands. Ironically, Europeans tended to be more seismically savvy in the 19th century than today.

Back then, scientists built their accounts of earthquakes largely from the eyewitness accounts of survivors. “Likely in no other field is the researcher so completely dependent on the help of the non-geologist,” wrote one 19th-century geologist; “and nowhere is the observation of each individual of such high value as with earthquakes… Only through the cooperation of all can a satisfying result be delivered.”

Even today, the most sophisticated seismographs alone can’t say how much damage a future temblor is likely to cause. That kind of information can only come from people on the ground sharing their observations.

As I discovered by reading dusty letters between scientists and citizen observers for my book on the subject, a lively dialogue emerged in the 19th century about how best to live with seismic risk.

Scientists learned what the readings of their instruments meant in terms of the felt experience of people on the scene, while observers developed a new curiosity about our dynamic planet. Reviving this dialogue could help Europe build a common language for earthquake safety today.

Deborah R Coen is a professor of history and history of science and medicine at Yale. Her book ‘The Earthquake Observers: Disaster Science from Lisbon to Richter’ is available to buy here