The former Massachusetts governor now spends his days trying to fix college sports. But if you think the NCAA president has said goodbye to politics, think again.

Illustration by Benjamen Purvis / Photo by Jamie Schwaberow/NCAA Photos (Baker) / Getty Images

Once upon a time, Charlie Baker says—before he was governor, before he was in politics, before he was anything, really—he wanted to be, of all things, a sportswriter.

“This is back in time, long, long ago, probably before your parents were kids, when there were daily newspapers everywhere,” Baker is saying. It’s a crystal-clear afternoon, and Baker, now president of the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA), is inside the organization’s national office in Indianapolis, addressing a few hundred college students interested in sports management careers.

This is the kind of setting that Baker—who’s long brimmed with a just-right mix of self-assuredness and regular-guyness—has always been at home in, and today is no exception. Looking relaxed in an open-collar shirt and speaking off the cuff, he’s funny, open, and direct, sharing his own story in hopes that it might contain some lesson for the students.

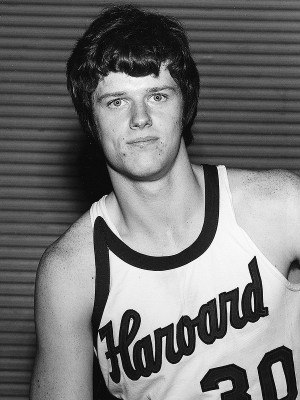

Baker posing in his Harvard basketball uniform in 1979. / Photo courtesy of Harvard Athletics

Back to the sportswriter dream: Baker explains that he played basketball in college—three years at Harvard, mostly on JV. He also began contributing stories to those small local papers that used to be everywhere, including the Daily News Transcript in Norwood. “I covered high school sports, college sports, pretty much whatever they needed somebody to write about,” he says.

Baker was so bitten by the sportswriting bug that, in the summers while he was at Harvard as well as post-college, he worked a loading-dock job during the day so he could continue stringing for the Transcript in his off hours, hoping that before long, the editors there—or somewhere—would give him a staff job, and he’d be on his way.

Alas, after a year of no offers—this was in the late ’70s, not long after Woodward and Bernstein had turned journalism into a glamour occupation and competition for jobs was fierce—Baker was finally persuaded he needed to pivot, career-wise. He landed a communications job at the Massachusetts High Technology Council, which got him interested in public policy, which led to him getting an MBA at Northwestern, which led to a job at a libertarian think tank, which eventually put Baker on the radar of a GOP gubernatorial candidate named Bill Weld. There were a lot more twists and turns from there, but we basically know how things ended up: Baker not only served two terms as governor of Massachusetts but became the most popular governor from sea to shining sea.

Baker’s point in telling the kids all of this? Well, in part it’s to urge them to be receptive to opportunities, to keep their “peripheral vision,” as he puts it, open. “This journey you’re about to go on, maybe everything will go according to plan, and bully for you if it works out that way,” he says. “But more often than not, it won’t.”

That’s okay, he continues. “Your goal here should be constantly trying to find places and spaces where you do stuff you’re good at and you enjoy. Bring the grind. Bring all that stuff you learned as an athlete. Be a good teammate.”

If they do that, well, who knows where they’ll end up? As Baker tells the kids, “Here I am, literally 47 years after I said I wanted to be a sportswriter, and I finally found my way”—Baker starts to bellow, in a sort of Masshole way—“INTO A JOB IN SPORTS! BUT IT TOOK ME 47 YEARS TO GET HERE!”

Baker in action at Ohio’s Hall of Fame Stadium during the 2023 Women’s College World Series. / Photo by Stan Grossfeld/The Boston Globe via Getty Images

Yes, Charlie Baker is now in sports, although it’s worth noting he’s taken on what just might be the worst job in all of American athletics: trying to fix the mess that is the NCAA. Over the past 15 years, the 118-year-old body that regulates sports for nearly 1,100 colleges and universities, from behemoths like Ohio State to wisps like Holy Cross—has found itself upended by the twin forces of hyper-capitalism and hyper-litigation, the result of which has been nothing less than chaos. High-profile schools regularly switch conferences in order to make more money. Bigtime athletes—who can now be paid—regularly switch schools, also to make more money. Meanwhile, sports-betting apps such as FanDuel have given fans the daily opportunity to be separated from their money. Since taking over the NCAA 18 months ago, Baker has, by most accounts, done an effective job in at least beginning to get things under control, but what college athletics will look like in the future is still something of an open question.

Sports, of course, is hardly the only area of life that’s been upended of late, as Baker knows maybe better than anyone. Indeed, one can pretty easily make the case that if politics—especially Republican politics—hadn’t been taken over by extremists, Baker would be sailing along in his third term as governor or perhaps even occupying one of two spots on the GOP presidential ticket.

But the world did change, and so Charlie Baker—a man shaped in a different era, the quintessential centrist, an uncommon finder of common ground—now spends his days trying to bring sanity back to college sports. Which isn’t to say he’s necessarily given up on trying to bring sanity back to politics, too.

Charlie Baker at the NCAA headquarters in Indianapolis. / Photo by Jamie Schwaberow/NCAA Photos

A few minutes after Baker’s chat with the students, he and I sit down in a conference room that overlooks the White River on the west side of Indianapolis’s spiffy, refurbished downtown. “Because this is a convention town, the number of hotels is just stupefying,” he says of his home away from home. “As is the number of steakhouses. We’ve got a steak place on every corner.”

Baker, who’ll turn 68 in November, typically spends two or three days each week here at NCAA headquarters and a couple more on the road, attending to NCAA business or taking in one of the thousands of sporting events—from bowling to water polo—that the organization oversees. On weekends, he tries to be back in Swampscott with his wife of 37 years, Lauren. “The Wonderfund is her passion project, and she needs to be there for that,” he says. He pauses, then adds, smiling, “We still like each other.”

When the news hit in late 2022, just weeks before the end of his second term, that Baker was going to be the NCAA’s new president, many people were surprised—including, to an extent, Baker himself. He and Lauren had been envisioning a different kind of post-gubernatorial life, a mix of consulting, speaking, and writing. But a couple of months earlier, Baker had received a call from Red Sox president Sam Kennedy. Would Baker be interested in heading the NCAA? (A search firm had reached out to Kennedy, mining for candidates.) “I laughed and said, ‘Sam, I haven’t been in higher education or college athletics,’” Baker remembers. “He said, ‘I know, but I read the job description, and you’re the first person I thought of.’” Baker was skeptical, but—peripheral vision always operating—he agreed to look at an overview of the position. He was intrigued enough to share it with Lauren. “She looks at me and says, ‘Yeah, this does sound like you.’”

The job description, he continues, “talked a lot about the complexity of the organizational structure, the 180 committees the NCAA has, governing, bylaws, challenges associated with getting everyone to work together…blah blah blah.” (Yes, Baker actually says blah blah blah, though the geeky details were undoubtedly part of the job’s allure.)

From the NCAA’s perspective, the governor was an attractive candidate not just because of his skill set and political connections but also because of where he was in his career. “I don’t think he was really worried about his next job,” says Springfield College president Mary-Beth Cooper, a selection committee member who had crossed paths several times with Baker when he was governor and championed Baker within the committee. “So his desire to solve the problems surrounding the NCAA and student-athletes was really born out of ‘This is something I can do,’ versus ‘This is something I have to do,’ or ‘This is going to get me my next job.’”

Which is not to say, given the NCAA’s massive challenges, that taking the gig wasn’t a fairly ridiculous decision by Baker. “I called a bunch of people I knew that had some tangential connection [to the NCAA],” he says, “and they were like…‘Oh, I’m not really sure that’s such a great next move.’ But the more I thought about it, the more I thought, you know, this feels a lot like service, and that’s kind of the way I’m built.”

The problems plaguing the NCAA have reached a crisis point in recent years, but they’ve been building for a generation and essentially revolve around one thing: money. Not too little of it, ironically, but too much of it. Indeed, over the past couple of decades, the amount of cash that TV networks have been willing to throw at major conferences like the Big Ten and SEC has skyrocketed. In 1994, CBS paid the SEC about $17 million per season for rights to televise its football games. Under a contract that begins this year, ESPN will pay the conference $300 million per season. At the same time, big schools have been able to leverage sports for sponsorships, donations, and other revenue generators. Last year, the football program at the University of Texas pulled in more than $180 million, with other bigtime schools not far behind.

Perhaps predictably, it’s led to a fight about who actually gets the cash. For decades, the NCAA stubbornly stuck to its model of “amateurism,” essentially saying that because sports are part of a broader educational experience, the only compensation athletes—or as the NCAA invariably refers to them, “student-athletes”—should receive is a scholarship to attend school. (Never mind that, in recent years, coaches at the biggest universities have gotten eight-figure annual contracts, nor that those same schools are spending hundreds of millions of dollars each on lavish training facilities.)

The first serious challenge to the NCAA’s model came when UCLA basketball player Ed O’Bannon filed a class-action lawsuit, saying that UCLA had benefited financially from the use of his “name, image, and likeness” (NIL) while giving O’Bannon bupkis in return. The case took years to wind its way through the courts, but in 2014, the U.S. Supreme Court sided with O’Bannon et al. The case ultimately ended with a mere tweak to the rules—schools were allowed to give athletes a $5,000 stipend put in a trust for their NIL rights—but it was the first legal crack in the NCAA’s façade. Seven years later, the Supremes ruled against the NCAA in another case, with Justice Brett Kavanaugh writing that the “NCAA’s business model of using unpaid student-athletes to generate billions of dollars in revenue for the colleges raises serious questions under the antitrust laws.”

Sensing the shifting winds, the NCAA quickly made two significant changes in the spring of 2021. One was loosening its onerous transfer rules, which had long forced athletes who switched from one school to another to sit out a year before playing again. Under the new guidelines, on their first school transfer, students could play right away. The second change was even more dramatic: Athletes could now accept an unlimited amount of so-called NIL money. At first blush, it appeared the NCAA was merely opening the door for kids to sign commercial endorsement deals, but it didn’t take long for deep-pocketed boosters at big schools to form “NIL collectives”—essentially giant pools of dough that could be handed out to the best players and most promising recruits.

The two changes have led to an atmosphere many call “the Wild West” in bigtime college sports. The problem isn’t just that athletes are switching schools every year, pursuing ever-bigger NIL checks (the going rate for a quarterback at a major school is said to be around $2 million per year). It’s that there’s little transparency, and fewer rules, around any of it.

This was the situation that was developing when Baker took the reins of the NCAA in early 2023. His first act was one familiar to anyone who’d watched him work as governor: to sit down and talk with as many people as possible. Over the course of his first six months at the NCAA, he traveled around the country, meeting with representatives from 97 different athletic conferences, including numerous athletic directors, coaches, staffers, and students. His goal was to understand their problems, their differences, and where the solutions might lie. “One of the things I’ve noticed about him is that he’s an incredible listener and an incredible notetaker,” Cooper says. She describes a meeting with Springfield’s athletic training staff in which Baker took seven or eight pages of notes.

The upshot of Baker’s listening tour? First, he identified some issues he could move on right away. Unbelievably, the NCAA had no project management system in place, nor did it have a database of its own fans. It now has both. Based on feedback from the schools, on Baker’s recommendation, the NCAA also implemented a mental health program for student-athletes, as well as an insurance program that protects kids in case of injury.

Still, Baker says the most important thing he learned during his listening tour was just how different schools are in the NCAA. The organization has long divided its members into divisions based on size, but even at the largest level, Division I, Baker says there are enormous differences: While some schools have $15 million annual athletic budgets, others have $220 million budgets. No less important is the role sports play at the institution. At some schools, sports really are just another part of the educational mission. At others—the powerhouses like Georgia, Alabama, USC, and Michigan—sports are first and foremost a revenue generator. “It’s an incredibly difficult challenge to take such a wide-ranging group of institutions…and try and put them all in the same bucket and serve them all the same way,” says Beth Goetz, athletic director at the University of Iowa (home for the past several years to phenom basketball player Caitlin Clark). “I think Charlie has openly recognized that there’s not a one-size-fits-all answer and response to every issue that might arise.”

Indeed, last December Baker made headlines when he proposed a new structure for those schools at the top of the athletic pyramid. Under new guidelines, the schools themselves would be able to offer direct payments into trust funds for athletes. It was a solution, many would argue, that was coming about 25 years too late, but internally it was a major step forward.

Meanwhile, Baker was busy negotiating with the plaintiffs in yet another high-stakes lawsuit against the NCAA. The “House” case, as it’s known, is a class-action suit demanding that universities give damages to many student-athletes who’d been screwed out of their NIL rights before 2023. In May, after winning the support from all of the major conferences, Baker announced a potential settlement in the case—one that would not only compensate those prior athletes but also put new compensation rules in place for the next 10 years. At the highest levels of Division I, each school could spend up to $22 million per year paying its athletes (in addition to any NIL money players might get).

The settlement isn’t final yet—the judge in the case still has to sign off on it. If the plan is approved, though, Baker’s December proposal effectively becomes moot. Still, the proposed “House” agreement doesn’t address another legal threat facing the NCAA, including whether athletes should be classified as “employees,” which would explode athletic budgets and potentially force small schools to drop sports altogether. Despite that, Baker is pleased by the progress. As he says, “Having gotten here a year ago and having talked to 97 conferences and having talked to tons of kids and grownups, the big message from all of them was, I really wish the ground would stop shifting every three months.” If the settlement holds, Baker will have done precisely that.

Baker at the NCAA Headquarters in Indianapolis, Indiana in 2023. / Photo by Jamie Schwaberow/NCAA Photos

If Baker has one big talent, it’s his ability to not just listen to various parties in any given situation but to synthesize what he hears and craft a path forward. In a different era, that capacity for consensus and compromise was considered a virtue; today, at least in the most extreme political circles, it’s perhaps the worst vice of all.

Baker’s knack for finding common ground is a byproduct, one supposes, of growing up in a household during the 1960s and 1970s with a Republican father and a Democratic mother who regularly talked about the issues of the day. “They used to argue about this stuff at the dining room table,” Baker remembers. “Friends of mine used to come over just to watch. And, of course, they weren’t really arguing. They were debating and discussing.”

Something about that image—a sit-down family dinner, first of all, but also two adults civilly disagreeing about politics and policy over meatloaf and mashed potatoes—seems quaint in our faster, harsher, more wired era. And it’s only one reminder that Baker came of age at a time unlike the one we’re in today. “We live in a world that is so profoundly different than the one I grew up in,” Baker said in a speech he gave in the fall of 2022, just months before the end of his term. “There were no portable phones. Cameras were cameras, and papers were typed on typewriters.”

Baker’s upbringing seems to have been particularly apple-pie-flavored. He had a paper route. He once built a basketball court in his backyard using railroad ties, gravel, and tar. He earned extra spending money typing papers for his buddies. Even his “dark” side—a fondness for beer and loud classic rock—seems wholesome.

The all-American ideals that were instilled in him—listen, work hard, be a good teammate, but don’t be a stick in the mud—ultimately served Baker well in his professional career. One of the people who spotted his promise was Bill Weld, who met Baker when Weld was making his first run for governor in 1990. Weld was impressed by all the stuff Baker knew about healthcare, and he called him frequently from the campaign trail to pump him for information. After getting elected, he made Baker, then 34, under-secretary of health and human services. Within a couple of years, Baker was leading the department, and he eventually became Weld’s secretary of administration and finance—a clear rising star in Republican politics.

Still, there were definitely some bumps in the road. In 2010, after spending more than a decade post-Weld administration as CEO of Harvard Pilgrim Health Care, Baker blew what many considered a winnable governor’s race against Deval Patrick. On a personal level, Baker was devastated, but in the months after the election, he put his listening and synthesizing skills to work, meeting one-on-one with reporters and politicos and asking point blank what he’d done wrong. One answer he heard frequently was about preaching to the converted—he’d avoided campaigning in places where he knew people disagreed with him. That was no way, he was told, to win a tight election.

The other criticism cut deeper. “People would say things to me like, ‘I’ve known you for a long time. I think we’re friends. I HATED you as a candidate, and I didn’t vote for you,’” Baker remembers.

It was pretty heavy abuse, but accurate. “One of the main reasons he lost was because he acted like a jerk in the debate and on the campaign trail,” says longtime Boston political analyst (and Boston contributing editor) Jon Keller. “There was a potent streak of jerk in Charlie—an ego and an obnoxious side—and that was on full display.”

Baker says he grew from both critiques, and when he ran for governor again in 2014, a New Charlie had emerged. He got his brusque side under control, and he made a point of campaigning in places where Republicans typically didn’t stand much chance of winning, talking to—no, listening to—voters who had different life experiences, different work experiences. He didn’t necessarily win many of those neighborhoods, but he didn’t lose by as much as he had four years earlier. He beat Martha Coakley in the general election by two points.

That approach—reach across partisan lines, try to understand the problem from all sides—became the playbook for Baker’s governorship. Granted, he didn’t really have much choice; he was, after all, a Republican governor in arguably the nation’s bluest state, complete with a heavily Democratic legislature. “His power was constrained,” Keller says, “so he had to work collaboratively, you might even say subserviently, to the Democratic majority. But he did it in a way that didn’t make him look weak.”

The occasionally combative but ultimately productive sharing of power was what many people wanted. Moderate Democrats in the legislature liked having a Republican governor since it let them push back against their more progressive colleagues—there’s no way the governor will go for that. The broader public also approved. By the time Baker and Lieutenant Governor Karyn Polito won reelection in 2018 with 67 percent of the vote, he was the single most popular governor in America.

Ironically, as governor, Baker long enjoyed higher approval ratings from Democrats than Republicans, a fact that would, in the age of Donald Trump and rising political extremism, ultimately become his political Achilles’ heel. Baker came out against Trump in 2016, supporting Chris Christie in the primary and not casting a vote for president at all in the general election. His never-Trumpness didn’t cost him much in his first term as governor, but by the time the pandemic hit in 2020, more strident voices, fueled by the Internet and social media, were gaining increasing sway. Indeed, Baker—who mandated vaccines for state workers—was not only dubbed a RINO by people in the Massachusetts MAGA movement but also fell into open warfare with then-state GOP Chair Jim Lyons, a major Trump booster. In mid-2021, with Baker still mulling whether to try for a third term, state Representative Geoff Diehl announced he was running in the GOP primary, quickly earning Trump’s endorsement. By the fall, one poll found Diehl leading Baker 50–29 in a potential Republican primary matchup.

The ground, to use Baker’s phrase, was shifting. Was he concerned about losing a primary? When I bring it up, Baker takes an indirect route to answering the question. “The lieutenant governor and I talked quite a bit about whether to run or not to run, the challenges, and all the rest,” he says. “And at the end, we basically decided that we’ve done a pretty good job of managing COVID without turning it into a political football. And not running for office would ensure that that would continue to be the case.”

Then he gets more to the point: “I always thought that if [we] had run again, we would have a very good chance of winning. I think we both felt like we had a pretty good understanding of where the people of Massachusetts were at on both sides of the aisle, and I think we were pretty confident if we had run again, our chances were pretty [good]…. But you know, turning all that stuff into a political overlay is just not something either one of us wanted to do.”

One can imagine the shift within the state GOP was difficult for Baker not just on a personal level—it was, in a way, a rerun of people telling him they HATED him—but on a practical level as well. “I think one of the reasons he didn’t run for a third term,” says UMass political science professor Tatishe Nteta, “was his recognition that Republican politicians in the state were less interested in winning elections and influencing policy and wielding power than in expressing an ideological position.”

Put another way, the new version of the Republican party was no longer interested in governing, in solving problems, in working things out with the other side. Baker—who left office with a 68 percent approval rating—was out.

Baker with national championship-winning volleyball player Logan Eggleston, Vice President Kamala Harris, and Second Gentleman Doug Emhoff during College Athlete Day on the South Lawn of the White House in June 2023. / Photo by ANDREW CABALLERO-REYNOLDS / AFP via Getty Images)

Perhaps because of the era in which he was raised (not to mention the fact that he built his own home basketball court out of gravel and tar), Baker deeply believes in the virtues that come from competing in sports. The habits it instills. The life lessons it imparts. He spent his youth playing sports, and so did his wife and their kids, as well as many of their friends and their friends’ kids.

What’s more, for all that’s wrong with college athletics of late, Baker makes the case that much remains very right. When I ask him, for instance, what he hopes the landscape will look like a decade from now, he doesn’t talk about expanding March Madness or the extraordinary revenue potential of a 12-team college football playoff (though the former is on the table and the latter is happening). Instead, he begins by talking about the smaller schools, which don’t get nearly the attention or acclaim of the big ones. “I’m going to assume DIII and DII are, hopefully, still able to kind of do what they do now,” he says. “Because they actually serve most of the kids in college sports. And having been to enough DIII and DII championships and tournaments and games, it’s very clear to me that the kids really like it, the schools really like it, and the fans really like it.”

Baker allows that Division I will change—the best athletes will be paid—but the fundamentals of success really won’t. “You’re still not going to win a lot of games unless you’re willing to be a good teammate and do the grind and be well coached and get a good night’s sleep and a whole bunch of other things,” he says, then adds, “99 percent of DI athletes, even in the most upper end, are not going to play professionally outside of their time in college. Most of them are going to need an education. Because even if they’re paid very well—and I hope many of them are—during their college years, they got a lot of life left to live after.”

In an ideal world, in other words, the student-athlete isn’t going anywhere.

Baker is happy—proud, even—that the top college athletes, at least in football and basketball, will be paid for their efforts, and it’s pretty hard to argue against that notion. It’s their performances—their skills, dedication, hard work—we’re tuning in to watch; denying them compensation under the guise of “amateurism” seems like the worst form of exploitation.

Yet it’s not hard to imagine a future in which bigtime college sports is essentially swallowed whole by monetary interests. Earlier this year, it was reported that Florida State was partnering with a private equity firm to raise capital for its athletic program, presumably giving the school more money with which to recruit top athletes. It seems inevitable that other leading programs will follow suit. And as universities essentially graft multibillion-dollar professional sports operations onto themselves, it’s fair to ask: What does any of this have to do with education?

It’s also fair to ask about the trickle-down effect. Already, many states (including Massachusetts) allow high school athletes to receive NIL money. With college recruiting now effectively starting in middle school, are we eventually looking at a scenario when a particularly promising 7th or 8th grader signs a six-figure contract, as long as he or she commits to a particular school?

When I wonder aloud if any of this concerns Baker, the pragmatist in him takes over. He tells me a story from when his own kids—now in their twenties and thirties—were teenagers. He remembers them huddling around the family’s computer (they only had one), watching videos of another kid who played hilarious songs. The kid was from Hamilton, it turned out, and his name was Bo Burnham. At the time, Baker remembers, he had maybe 500,000 YouTube followers. But a year later, he had a million followers—and all kinds of partnerships. “Bo was making a lot of money because he was a phenomenal talent at a really young age,” he says. “You always worry about that stuff with young people. There are lots of examples of young people who were child stars and managed to get through what must have been an incredibly disorienting period in their lives to be successful as adults. And there’s a bunch that didn’t. But I don’t think we should say that if you’re a young actor or musician or clothing designer, you can get paid for it, but, gee, if you’re a basketball player, you can’t. I don’t think societally we can do that.

“I think the Internet and social media changed everything about this,” Baker says finally. “And whether it’s good or bad, I suppose time will tell.”

Baker delivering the State of the Commonwealth Address in 2022. / Photo by Barry Chin/The Boston Globe via Getty Images

As Baker well knows, the Internet and social media have changed politics as well.

The division and extremism we see—which arguably brought an end to Baker’s political career—are directly tied to the ideologically curated content we’re served up online; to the websites and social media that give oxygen to conspiracy theories; and to the social media influencers who only see the world in black and white, never gray.

I ask Baker what happened to the Republican Party he was once a star of, and he points me to that speech he made in the fall of 2022. It was actually the Godkin Lecture, the annual address sponsored by Harvard’s Kennedy School, which over the years has featured remarks by a range of influential thinkers, from Lord Bryce to Daniel Patrick Moynihan.

Baker, with just weeks to go as governor, used the lecture to talk about our country’s political divide. He discussed the technology that engulfs us, calling it a mixed blessing: We can do things we could never do before, but the world is also filled with misinformation and extremism and less tolerance of divergent viewpoints. What’s more, he said, the Internet has pushed the two main political parties farther to the left and the right. The parties no longer tolerate people who are not ideologically pure, and party leaders seem to spend most of their time accentuating the other party’s most extreme positions.

“Why do they play the game this way?” Baker asked in the speech. “My conclusion is a simple one. Both parties and their candidates believe this is how they can win…. Outrage and false information travel farther, faster among partisans and advocates on social media than anything that looks like straight news. Advocates use these outlets—and others—to keep their supporters outraged and engaged and to inflict discipline on elected officials.”

Then Baker got to his main point: Just because America’s political parties are farther apart than ever before, does that mean Americans are as well? He insisted the answer was no.

Three or four decades ago, Baker explained, the country’s electorate was split about equally among Democrats, Republicans, and Independents. But since then, the number of Independents has grown substantially—it’s now closing in on 50 percent—while the number of Democrats and Republicans has withered to about 25 percent each. “As the two largest parties became less and less able to tolerate dissent, voters who carried around a mix of ideologies on policy found less and less room in either party for their points of view. And they left.”

The crux of the matter, Baker tells me now, is that we’re not really as divided as the media and others make us out to be. “My own experience, generally in public life, is that people, for the most part, agree more than they disagree,” he says. “The problem we all live with now is that’s just not very interesting.”

From the moment Baker announced he wouldn’t seek a third term as governor, there’s been speculation about whether he was done with politics for good.

From the moment Baker announced he wouldn’t seek a third term as governor, there’s been speculation about whether he was done with politics for good. Many pundits have pointed to the fact that Massachusetts has two U.S. senators in their seventies, including Ed Markey, who’ll be up for reelection in 2026. Would Baker challenge him or run for his open seat should Markey choose to retire?

Baker has always given a non-answer—“A politician never says never”—and he sticks with that when I bring it up. “I’m really enjoying what I’m doing,” he says. “And I’m not getting any younger.”

But when I dig deeper about a potential Senate run, saying I actually wonder if he’d even be happy as a legislator, he seems to open the door a little. I find myself thinking about what Baker told the students about the journey and peripheral vision and finding spaces and places where you do things you’re good at and enjoy. “You tend not to ever get too definitive about any of this stuff,” he says. “If you told me in the spring or summer of ’22 that I was going to be working for the NCAA, I would have found that to be an unusual question. But I have talked to former Governor, now Senator, Mitt Romney about being in the Senate, and he said it was a pretty interesting place.

“Look,” he continues, “I obviously enjoy public service a lot. And I, generally speaking, would never rule out doing something in the public sphere. But I’m very happy where I am, and I don’t anticipate being anywhere else anytime soon.”

Make of that whatever you wish. A sign Baker is never going to run. A sign he’s absolutely going to run. A sign he legitimately hasn’t decided. Could he make it through a primary if he ran as a Republican? And if he did, would Democrats, who’ve long crossed the aisle to support him, do so if control of the U.S. Senate was at stake?

Baker was forged in a different age, and in many ways, he can seem out of step with where we are now. He’s a man who sees virtue in sports at a time when sports are mostly about money. A political moderate at a time when the extremes have taken over. A guy who believes in being useful and being a good teammate and bringing the grind. Despite newspapers dying, typewriters going away, and our phones turning into computers and cameras, Baker has a hunch you still believe in all of that stuff, too.

First published in the print edition of the September 2024 issue with the headline, “Charlie Baker’s (Still) Got Game.”