Mexican lawmakers narrowly approved a sweeping overhaul of the judiciary early Wednesday, hours after hundreds of protesters broke into the Senate chambers in a chaotic scene that briefly delayed the vote.

Senate approval was the last major hurdle for the constitutional change, which calls for Mexican judges to be elected by popular vote.

The proposal’s passage by a razor-thin margin was a huge victory for outgoing President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, a populist who has repeatedly clashed with Mexico’s courts during his six years in office, and who insists the changes will make judges more accountable to the people.

Opposition to the proposal has surged in recent weeks, with legal experts, business leaders and even many of the president’s leftist allies saying that it will undermine crucial checks and balances and strengthen the power of López Obrador’s governing Morena party.

Thousands of Mexican judges and other court staff have been on strike in protest in recent weeks, paralyzing the country’s legal system. The peso has plunged amid concerns that the overhaul could discourage foreign investment.

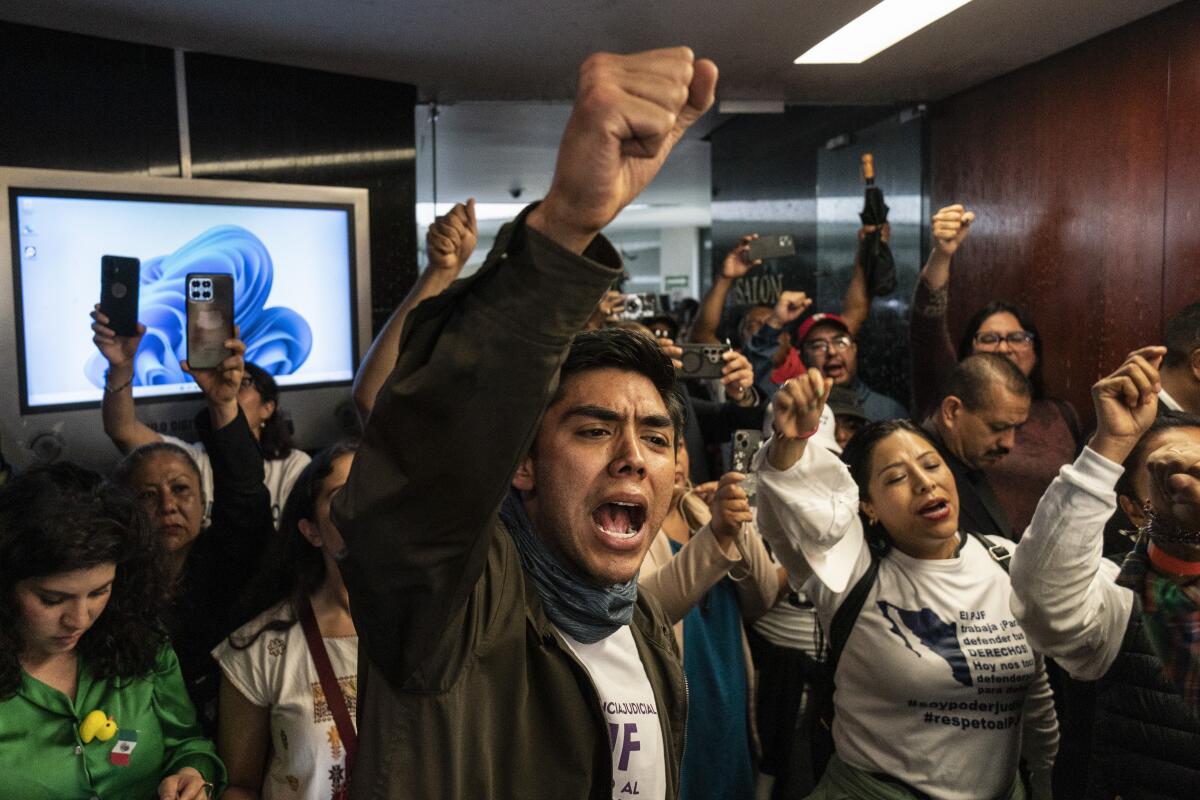

On Tuesday night, as lawmakers gathered to weigh in on the proposal, hundreds of judges and other protesters used pipes and chains to break into the Senate chambers in an effort to block the vote, which they framed as an existential threat to Mexico’s democracy.

“They have decided to sell out the nation,” Alejandro Navarrete, a 30-year-old judicial worker, told the Associated Press. “We intend to make it clear that the Mexican people won’t allow them to lead us into a dictatorship.”

Protesters in Mexico City’s Senate as lawmakers weigh the government’s proposed judicial overhaul.

(Felix Marquez / Associated Press)

Lawmakers eventually decamped to a nearby museum to resume their session. Though Morena lacked the supermajority in the Senate required to pass a constitutional change, its leaders were able to convince several senators from opposition parties to support the overhaul.

One of those lawmakers was Miguel Ángel Yunes of the center-right National Action Party, who belongs to a family of conservative leaders that López Obrador has frequently accused of corruption. Critics of the judicial overhaul questioned why Yunes decided to suddenly switch allegiance to the party he has long opposed, and questioned whether there had been some kind of deal.

Yunes, speaking to reporters, denied that. “I have the right as a senator to express my opinion and my vote in the way that I consider best,” he said.

Morena leaders celebrated the passage of the overhaul, which they portrayed as part of López Obrador’s larger project of transforming Mexican democracy to better represent its masses, as opposed to wealthy and politically powerful elites.

“With the election of judges, magistrates and ministers, the administration of justice in our country will be strengthened,” said the incoming president, Claudia Sheinbaum. “The regime of corruption and privileges is becoming more and more a thing of the past, and a true democracy and a true rule of law are being built.”

The lower chamber of Congress approved the reform proposal last week, with lawmakers forced to cast their votes from inside a sports stadium because the doors to their headquarters had been blocked by angry demonstrators. To become law, the constitutional reform will have to be approved by a majority of Mexico’s state legislatures, most of which are controlled by Morena.

President Andrés Manuel López Obrador waves to supporters at Mexico City’s Zocalo this month.

(Felix Marquez / Associated Press)

Under Mexico’s current judicial system, those hoping to become federal judges must undergo training, pass public exams and be evaluated by an oversight council. The president nominates three candidates for each vacancy on the Supreme Court, and the Senate approves one.

López Obrador’s proposal would make the country’s entire judicial branch — around 7,000 judges — stand for election.

The number of judges serving on the Supreme Court would shrink from 11 to nine, and their term would be shortened to 12 years from the current 15.

Critics of the plan warn that elections would turn judges from impartial interpreters of the law into political actors who might issue decisions to win votes or to please campaign donors or even criminal organizations.

López Obrador pushed the plan after several of his key legislative efforts — including a proposal to cede control of the National Guard to the military and another to increase the role of the government in the energy sector — were blocked by judges who he says are corrupt.

The proposal has drawn extensive criticism, from Mexico’s trading partners, international experts onthe rule of law and eventhe Catholic Church. Church leaders in Mexico said this week that they were praying that senators reflect on the responsibility before them.

Critics are concerned about the proposal because the Morena party holds an overwhelming majority in Congress. If voters elect judges friendly to the party, Morena would effectively control all three branches of government. Some warn that it would return Mexico, which was ruled by a single party for most of the 20th century, to a one-party state.

Linthicum is a Times staff writer and Sánchez Vidal is a special correspondent.

Read more coverage of Mexico and the Americas.