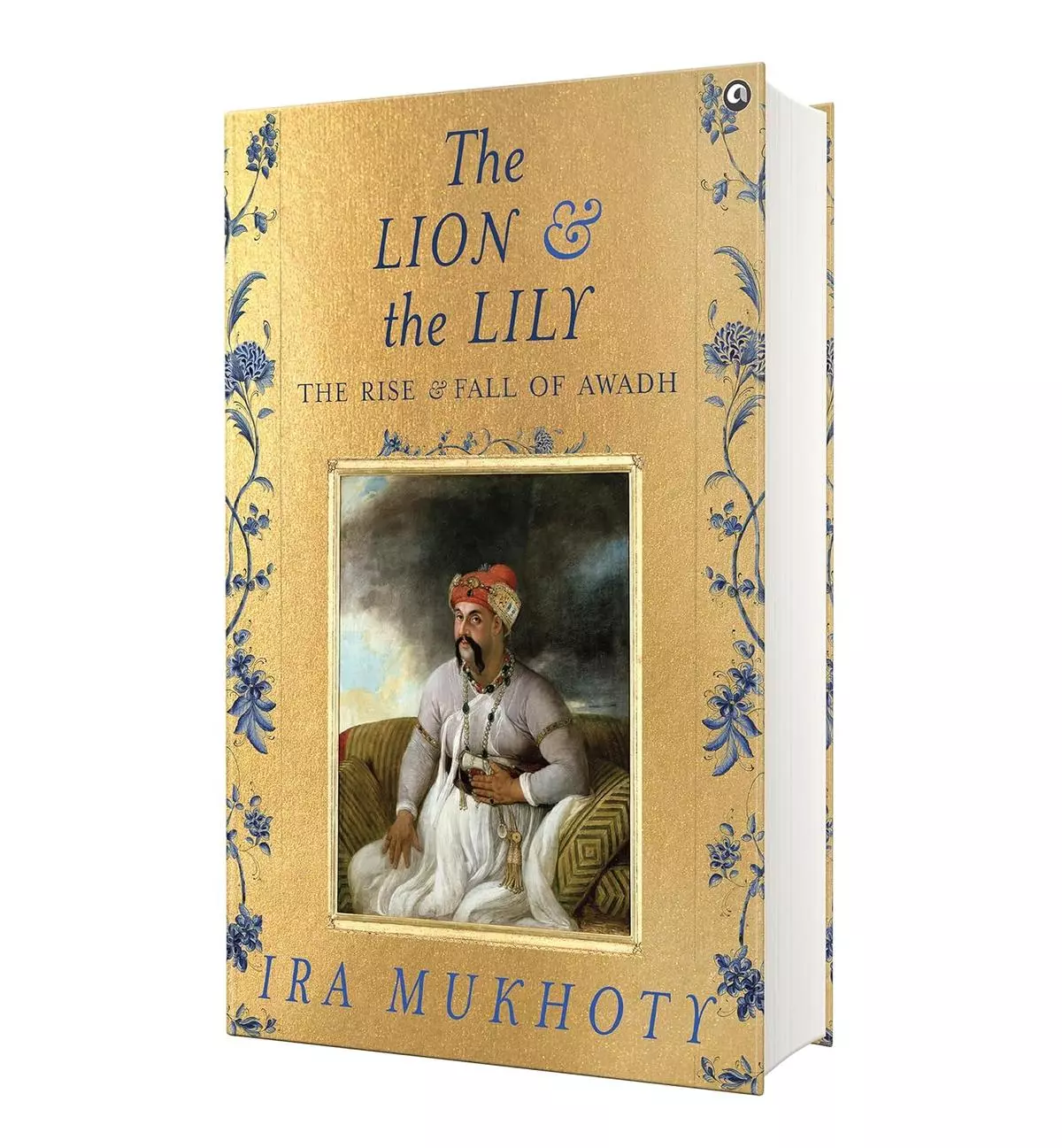

Historian Ira Mukhoty’s latest book, The Lion and The Lily: The Rise and Fall of Awadh, challenges long-held views about the fall of the Mughal Empire and the rise of British rule in India. Through her focus on the kingdom of Awadh, Mukhoty reveals a complex narrative of regional courts resisting British imperialism while engaging in international diplomacy.

In a discussion with Anirudh Kanisetti for Frontline, she talks about the capable rulers of Awadh, the French influence in 18th-century India, and how British propaganda has shaped our understanding of this pivotal period. Mukhoty’s work, drawing from diverse sources, offers a fresh perspective on a transformative era in Indian history. Edited excerpts:

To begin, how did you decide to focus on the Awadh region for the book?

Initially, I thought I would focus on the French influence: what they were doing during the late 17th century, how they were evolving in the 18th century, etc. But I realised that it would be more interesting to focus on French involvement through the provinces that were using their influence and to see how they were able to navigate these treacherous currents with the British, the French, and the other regional rulers. We believe we began our story after the Battle of Plassey. But that’s not true. Following Plassey, there was the Battle of Buxar, which is more important because Bengal, Bihar, and revenue generating resources were taken over by the British.

The next province that came into the line of fire was Awadh because it was the “buffer region” between [erstwhile] Bengal and Mughal Delhi. But it was also an extremely prosperous region that was ruled by the Nawab of Awadh, an ambitious and capable man. So, I wanted to show what happened in Awadh, when the French were starting to get involved and the British were casting a leery eye on the region’s resources.

I thought that would be a good way to navigate the second half of the 18th century. Several changes occurred in India during that time, that is, from a medieval past to the early modern situation. It showed how a new province was able to stand up to the British using means that we don’t think of as traditional. Awadh was a good place to start.

WATCH | I often compare Indian history with Game of Thrones: Ira Mukhoty

Historian Ira Mukhoty’s latest book, “The Lion and The Lily: The Rise and Fall of Awadh”, challenges long-held views about the fall of the Mughal Empire and the rise of British rule in India.

| Video Credit:

Interview: Anirudh Kanisetti; Editing: Samson Ronald K.; Production Co-ordinator: Abhinav Chakraborty; Produced By: Jinoy Jose P.

Where did the family that ruled Awadh descend from and how did they come to rule over the region?

So, they came from neighbouring Persia (the Persian empire), which in the late 17th and early 18th century was crumbling. So there were many talented officers and elite men coming to India from Persia to look for work at the Mughal court, which was, at the time, hanging onto the last of its lustre. A nobleman called Saadat Khan, from Nishapur in Persia, was employed at the Mughal court and was given the subah of Agra to manage. But after he had been unable to quell a Jat rebellion taking place around Delhi at that time, as punishment he was sentenced to Awadh, where he established a hereditary province.

After him, his son-in-law Safdarjung succeeded him, and then Safdarjang’s son, Shuja-ud-Daula, who is the focus of a major portion of the early bit of my book because he was the man who transformed Awadh’s destiny. He was present at the Battle of Buxar and when he was defeated, he used all his energy to make Awadh a great political and cultural centre.

Also Read | Unmasking the true nature of the Empire

With respect to Shuja, you chronicle interesting anecdotes from his life including the time he climbed into a young lady’s apartment in Banaras and how his parents responded to the incident. Could you elaborate on this affair? Could you also explain the philosophy of kingship: how Awadh’s rulers, who came from Persia, viewed themselves?

Shuja-ud-Daula was caught trying to sneak into young ladies’ homes many times. These were not women he was engaged or married to. In stark contrast to what happens in India today, where wealthy parents try to hide their children’s transgressions through bribery, his parents, Nawab Begum and Safdarjang, punished him. They instructed the court to treat him like any ordinary criminal. He was taken to prison, kept there, and was not allowed to change his clothes.

He remained imprisoned for months until Nawab Begum interceded on his behalf and allowed him to return to court. This shows how seriously Nawab Begum and Safdarjung viewed their roles as rulers of this region. They wanted to show their son that this kind of egregious behaviour against women, against another community, would not be tolerated. This seemed to have had a strong impact on Shuja-ud-Daula.

When he returned to Awadh after the debacle of Buxar, one of the men from the English [East India] Company wrote about the significant change he noticed in Shuja-ud-Daula who had suddenly taken an interest in ruling the region, promoting industry, construction, culture etc. Shuja’s strong sense of responsibility to the people became clear through his efforts to encourage trade, set up factories to manufacture guns and muskets, and improve technology. He was worried about Awadh’s defence. He was not a man who would sit back, relax, and enjoy his wealth. He was committed to making Awadh a greater centre of culture and political importance. We can see how these rulers viewed their role in society as protectors.

Shuja-ud-Daula, Nawab of Awadh. Mukhoty says that Shuja was committed to making Awadh a great centre of culture and political importance.

| Photo Credit:

By Special Arrangement

While the Mughal court was able to absorb officials from neighbouring Persia, the court at Awadh was able to attract people all the way from Europe. You spoke about how you were interested in the activities of the French during the 18th century. Could you elaborate on how the French became involved in India and Awadh in particular?

The role of the French during the 18th century is interesting and largely forgotten. As Maya Jasanoff had written in Edge of Empire: Conquest and Collecting in the East, 1750-1850, we cannot look at the way India developed and the role the British played without looking at France in parallel. During the 18th century, the Portuguese, the Dutch, and the other colonising forces were out of the picture, and it was Britain versus France in this huge global struggle for supremacy during the 18th century. France had started the 18th century with a bigger land army than Britain. Britain was this tiny island with a small population so they always had this anxiety vis-à-vis France but they started increasing their colonial empire by the mid 18th century.

In 1763, at the end of the Seven Years’ War—which was an important war over their holdings in North America, the Caribbean, and the rest of the world—Britain and France divided their global empire between themselves, and a peace was brought. In response, the French, who had been on the losing side of the war, began a “guerre de revanche”, or war of revenge, against the British. They started modernising their army, increasing their naval capabilities, which until then had not been on a par with that of the British. They ventured to different corners of the world with orders to block British power wherever they could. It wasn’t a war to conquer new territories but a war to, specifically, block British interests.

In India, once Pondicherry [present day Puducherry] and Chandannagar had been destroyed by the British after the peace of 1763, these officers, adventurers, and military men found themselves in the powerful courts of India with these specific aims to block the British wherever possible and help Indian rulers who were receptive to their ideas and willing to take on new ideas for technology and military improvement.

That is what Shuja-ud-Daula does. He completely reformed his army, his huge infantry, with the help of the French. A particular character whom I talk about, Jean-Baptiste Gentil, had hundreds of French people employed at his court to make it technologically superior to what it was before and equal to that of the British. Around 1765, he had 30,000 trained troops along the lines of the European fighting forces. Several Indian rulers were willing and able to take on their technology. We can see that rulers like Shuja-ud-Daula and Tipu Sultan (in Mysore) were extremely capable: they invested money and transformed the technology of their armies.

“I have now strongly come to the conclusion that if you see a particular Indian ruler whom even we now think of as very inept, useless, effeminate, and debauched, it means that they were actually capable rulers.”

I would like to discuss the narrative structure: In the first few chapters, you explore these dramatic political events that shape Shuja’s character, you then focus on the court established in Awadh, its various characters, the interactions between the begums and their retinues, and the interesting ways in which food culture was interlinked with political culture. How did you decide on this narrative structure? Can you tell us more about the Awadh court and the individuals who frequented it? Also, how did they handle diplomacy with the burgeoning part of the East India Company always at the doorstep?

I think stories of individual characters whom I can flesh out and bring to life are something that appeals to a lay reader. I find these characters fascinating. I often compare our history with that of Game of Thrones. Ours is just as interesting, just as bloody, just as full of treason and all sorts of skullduggery. These places can be brought to life by talking about the characters. I spent a lot of time on the characters and I wanted to highlight that people were not, at this point, defined by their religion.

We often think that all Europeans are Christians. But this is not the case. The French and the British are pitted against each other, despite being Christians, because one is Catholic and the other is Protestant and that is essential to their sense of identity. It is a cosmopolitan cast of characters. Somebody like Antoine Polier, who was a Frenchman, technically a French speaker but also a Protestant, which made it easier for him to align his interests with that of the rising East India Company. Such examples help to bring out the nuance of a textured court with Afghans, Persians, people from present day Türkiye, and various Europeans with conflicting interests.

With respect to how diplomacy was carried out, the spy system is something that we don’t think about today. But the spy system or espionage was important in the late 18th century. It’s how all Indian rulers kept watch on their powerful neighbours. They would send harkaras, or messengers, to spy or to relay information at every court of importance. The British became incredibly skilled at doing this even though initially they didn’t know how to acquire information about these courts and were on the back foot.

So, what the begums, for example, were doing was an interesting way in which they carried out their diplomacy: by using elite eunuchs of the 18th century (who were called khwajasaras) to access the outside world. These eunuchs were well educated, they carried out the [duties of] messengers and the orders of these women. These men were sent to Calcutta to speak to the councilmen. I found this interesting because the British men were uncomfortable dealing with these khwajasaras.

While writing the book I discovered that one of the men I write about, Antoine Polier, was in fact a spy who was working for various courts and selling information to whoever paid him the highest price. There was no sense of loyalty to one ruler, so diplomacy was an intricate matter that required knowledge of all sorts of courts. I was impressed by how the begums participated in negotiations with the Mughal court in Delhi.

Coming to Tipu Sultan, you wrote about how he tried to cultivate Louis XVI’s court. Can you elaborate on Tipu Sultan and the French? How did he develop his interest in this kingdom and how did he conceive of an embassy? And how were these embassies to France received?

The French considered Hyder Ali and Tipu Sultan their oldest and longest-serving allies and friends. I think what’s interesting is that Hyder Ali first came across the French when he observed [Joseph François] Dupleix, the successful French governor-general in the South who was successful against the Nawab of the Carnatic. He was the first man to use French-trained troops to defeat a Mughal army. Hyder Ali too realised that these were the men to court and have on his side, because he had gauged how aggressive and ambitious the British were. So he allied with the French, which his son continued.

The French were also sympathetic towards Tipu Sultan and thought of him as their strongest ally, more than any other ruler in India. This was because he—and Hyder Ali before him—were the only rulers to send embassies to France as they had a pragmatic idea of what was happening in the world vis-à-vis the global war. Only Mysore was aware of what was happening because of the information they received via embassies.

Then the French Revolution was about to happen but he had already sent his embassy to France by 1788. They arrived in style: there were three main men from his court and, of course, their entourage—they arrived with chefs, cooks, equipment, clothing, etc. People gathered around them whenever they stepped out on streets, to see the clothes they were wearing. Furthermore, people apparently gathered around the chefs when they were making food as they wanted to know what ingredients were used. But considering it was around the time of the French Revolution, the members of the embassy were greeted with warmth and curiosity but also suspicion.

It was a tricky time for Tipu Sultan to send his embassy as it represented a sense of heightened exoticism and luxury, which was associated with the upper class at a time when the common people hardly had any food to eat. Nonetheless, they returned in good health. These are the links of friendship that tied Tipu Sultan to France.

Even the revolutionary government decided to maintain links with Tipu Sultan because they realised that he was the only man who understood the role of the French. The only problem they have is that they had to make him understand that they could no longer call him the Sultan of Mysore. He had to be called le citoyen, an ordinary citizen. But Tipu Sultan, being the pragmatic man that he was, carried on corresponding and trying hard to get the French to send him the support he needed.

Also Read | Nandini Das: ‘Sense of uncertainty haunted the English in Mughal India’

I enjoyed the gravitas and humanity you brought to Tipu Sultan, who is often thought of in polarised terms.

Tipu and Hyder Ali were trying to improve their countries: agriculture, type of cattle that were being reared, manufacturing all sorts of goods, etc. Tipu Sultan has been associated with the British narrative of him as a warrior they were able to defeat. He had another side and he used all the resources at his disposal to modernise his country.

Anirudh Kanisetti, historian, researcher, and author of Lords of the Deccan.

| Photo Credit:

X/AKanisetti

You highlight an interesting pattern in the book: the way British imperialists spread rumours about Indian rulers of a region they wished to conquer as being too feminine, the women being too masculine, their over-indulgent lifestyles, etc. As a result, the British were seen as the only “solution” to India’s lack of able rulers. How did this differ from the way the French saw India? Could you comment more about how the British have shaped our memory of this period?

While writing the book, I realised that the British have been successful at [spreading this] propaganda. There’s no other empire in the world that has left the kind of legacy they have simply because their propaganda machine was so extraordinarily fine-tuned. With respect to the French, whenever I came across recordings of how the French were writing about the Indians, there were two aspects. They had a lot of admiration and awe for the Indian culture of the 18th century, and they had this idea that India was unchanging. This is a French point of view that has existed to this day: people in France will often talk about eternal India, its unchanging values and ways, which have lasted for millennia.

The second aspect was of an India that needed to have its chains broken. They viewed the British presence in India with a great deal of abhorrence. They felt the British had put chains on the rulers. They were seeking to debase them. It’s unbelievable that they managed to conquer a large territory with a few thousand soldiers.

So as opposed to the British who had a concrete vision of conquering the land, the French had a different idea. This was perhaps because the French East India Company was always state-governed. So, the king and his ministers, and court’s philosophers were always part of the decision-making process. Their idea focussed on blocking the British wherever they could, and breaking the chains of the Indians.

But when the French Revolution happened, theoretically, “liberty, fraternity, and equality for all men” did not extend to the Indians. There was always a slight dichotomy.

I have now strongly come to the conclusion that if you see a particular Indian ruler whom even we now in our national consciousness think of as very inept, useless, effeminate, debauched, such as Wajid-ud-Daula, or very despotic, demonic, bloodlusty sort of ruler like Tipu Sultan, it means that they were actually capable rulers. This is because the British were fearful of such rulers and attempted to diminish their legacy in every possible way.

When I was conducting the final rounds of my research, I discovered “Operation Legacy”. They established this system when they were exiting the colonies. All the incriminating documents left in these countries were either destroyed or taken back to England. The British did not want these documents to see the light of day and wanted people to remember them with “respect and affection”.