This story contains sensitive information about the Nanaimo Indian Hospital and the extreme violence that happened there, including sexual assault. For help, Indigenous peoples across Canada can call the Hope for Wellness Helpline at 1-855-242-3310 or chat online. The helpline’s counsellors are available 24/7. You can also call or text VictimLink BC at 1-800-563-0808.

For decades, Melven Jones couldn’t talk about what happened to him as a child. He didn’t even remember it.

Until one day in the shower, it all came rushing back.

“(My friend) came in, found me in the shower in the fetal position not moving. Nobody knew what was going on. I didn’t even know what was going on,” Jones said.

“I sputtered out that, ‘They hurt me. They really hurt me.’”

A mental block had broken, illuminating childhood horrors long hidden in the recesses of his mind.

Jones, a member of the Snuneymuxw First Nation, remembered being taken away from his family and sent to the Port Alberni residential school at the age of six.

“I only stayed there for two or three days,” said Jones, now 67. “Then they shipped me to Nanaimo Hospital.”

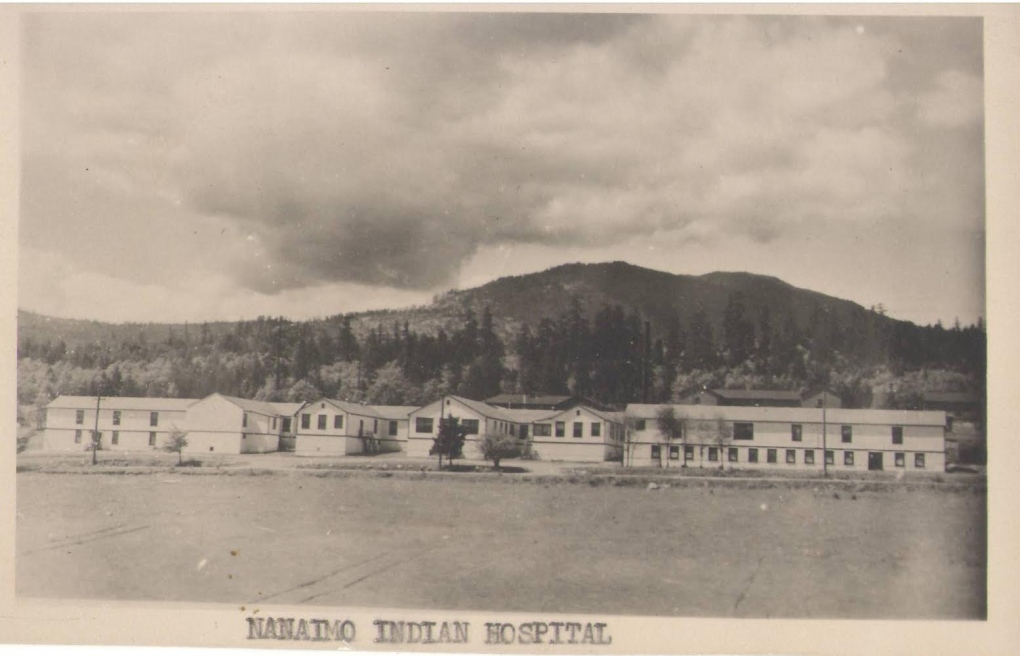

He was sent to the Nanaimo Indian Hospital — a segregated sanatorium for Indigenous people infected with tuberculosis. Survivors have reported medical experimentation, forced confinement, abuse and forced or coerced sterilization.

Jones said according to his health records, he wasn’t even sick.

“I didn’t have TB. They gave me TB,” he said.

It wasn’t the worst thing hospital staff subjected him to.

“The thing that affected me the most is that I got raped in there,” Jones said. “It took a long time for me to get away from that rape. A long time.”

He also remembers being strapped to a hospital bed and taken to a secluded room, where he underwent “shock treatments” on multiple occasions.

“I didn’t know why at that time, but I know now. Because they wanted to get the Indian out of me,” he said.

‘He’ll never get hurt again’

Jones was released from the hospital shortly before his eighth birthday.

The Canadian Medical Association recently apologized for medical harms inflicted on Indigenous peoples.

“As the national voice of the medical profession, we are sorry for the actions and inactions of physicians, residents and medical students that have harmed Indigenous peoples,” CMA president Dr. Joss Reimer said during the apology ceremony in Victoria on Sept. 18.

It doesn’t mean much to Jones. He had started moving forward well before the apology.

Nearly six decades after leaving the hospital, Jones had a lung transplant, ridding himself of the damage caused by tuberculosis. The damage to his psyche lingers, but is a shadow of what it once was.

“I can’t say I’m recovered, but I’m at rest with what happened to me. It’s not nice what they’ve done, but I forgive them,” he said. “It took me a long time to say that.”

A long time, paired with extensive therapy.

“If it wasn’t for (my psychologist), I would never be talking about this at all,” Jones said.

She taught him to care for his inner child, who he calls little Mel.

“He’s right here,” Jones said, putting his hand to his heart. “He’s happy and he’s safe and he’ll never get hurt again.”