One of the strange, hard-to-grasp questions that quietly haunts a lot of games is whether we are the people we are controlling. Whether we are meant to be those people, anyway. Are we Mario, or are we his custodian for the hours in which we play? Is there one of us involved in these jumps and dashes and Goomba stomps, or two of us, and where are the boundaries to be found? Sometimes the controls in a game are so intuitive that it really feels like it’s us on the other side of the screen. We’re in sync. And then something will happen – a glitch, a funny movement, a cut-scene – and the gap between avatar and player becomes jarringly visible. It’s odd stuff and tricky to think about for long stretches of time without starting to feel a bit weird.

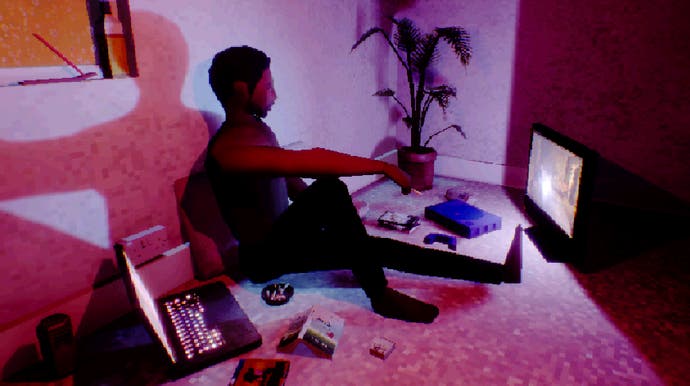

Apartment Story is a short narrative game about a man who lives in a small apartment and is quietly running out of options. His apartment is blandly pleasant but claustrophobic. His bank account is overdrawn and his life in general seems rattly and hollow. Over the course of an hour or so, all of this changes. There’s a woman, another man, and a gun. Things race towards an ugly climax.

And yet race is not the right word at all, because while events pile up swiftly, somehow they do this while you, living as or alongside the man in his small apartment, still have a lot of blandly aimless time to fill. Writing or porn on the computer in the bedroom. The making of small, disappointing meals to eat. When to rest, when to turn off the lights to conserve electricity. When to do a bit of a tidy up and when to think about handling the dishes.

In between the fights and the personal intrigue and the looming threat, this stuff should feel like a distraction, but in fact it’s the other stuff that distracts. I’ll be in the middle of a tense stand-off and I’ll be thinking: gah, didn’t clear the table before all this drama unfolded, that was a missed opportunity!

And a lot of this comes down to the way the controls work, and that question of how the player and the on-screen avatar are related. You are the man in the apartment, but you also aren’t him: he’s awkward and slightly indirect to move around, and your button presses are often met with a purposeful pause that keeps you both separated, both of you under glass and mouthing words back and forth. Sit down. Okay, I will. Eat. Alright then.

It’s kind of like being a puppeteer, or directing the movements of distant chess pieces over ham radio – I say it’s like this, I’ve never done either. Anyway, it gives the world a wonderfully maddening kind of urgency. By removing you from the surface of the action a little, everything in the apartment becomes very important. Gosh, it’s going to take an age to shower, to get dressed, to pick up all the CDs that have been flung around. The domestic toil becomes a kind of drama of weariness.

Ultimately, I think this goes towards making Apartment Story a character study as much as a compact piece of noir. Again: we are this man, but we also aren’t. We make his choices but we also observe him. I set him making dinner or getting a beer, but I wish I could ask him about the neon crucifix by his writing desk. I ensure he stays showered and is nicely dressed, but I also monitor the series of on-screen meters that hint at his mental state, his sleepiness, his urges, and that very act of meter management just makes his mental state seem more distant, more unknowable. It all makes for a game that’s fascinating in its capturing of a very specific experience of mundanity. It’s a short story, but when I left that apartment at the end I felt like I’d been there for weeks.