“I’d always been a huge fan of the first film,” says Alistair Hope, Alien: Isolation‘s director, of the original 1979 movie . “But everyone was always focused on the Aliens experience, given its natural connection between aliens and shooting. We felt that if you could create a game that took you back to that feeling of being on the Nostromo, hunted by that first alien – that would be something else.”

By the early 2000s, Sussex-based developer Creative Assembly had already established itself with a solid range of sports titles, but the real breakthrough came with Shogun: Total War. After that hit, and the Total War series’ subsequent success, the developer’s landscape changed, ultimately tempting Sega to acquire it in 2005. Just over a year later, Sega also acquired a licence to make games based on 20th Century Fox’s famous Alien series, planning ‘multiple titles’. Creative Assembly, coincidentally stuffed with Alien fans, put its hand up.

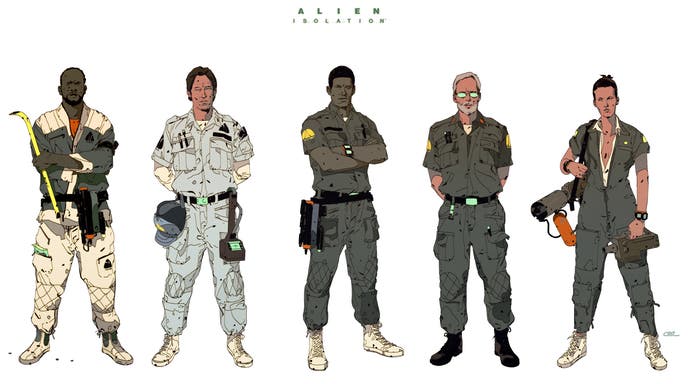

Hope wrote out a short proposal for Sega. “It wasn’t very much – outlining the kind of cat-and-mouse gameplay of being hunted by this unpredictable predator,” he tells me. “I was keen for it to be closely associated with Alien, taking advantage of the wonderful production design on that film, a sort-of low-fi sci-fi Seventies view of the future.”

But the move away from the prevailing emphasis on action – a perhaps inevitable focus since James Cameron’s 1986 sequel Aliens – was the thing that swung it. “We thought, let’s re-establish this thing as being the ultimate killer, a creature confident and in control,” continues Hope. “So, it went to Sega, through to 20th Century Fox, and suddenly someone is saying, ‘OK – go ahead, make it happen’.”

“Alien is 116 minutes long,” Hope says, “I was telling the team: nothing else exists. Forget the other movies. We only have this 116 minutes of source material.” Yet creating hours of playtime, from less than two two hours of tense cinema, turned out to be something of a challenge. “We knew we needed to create new stuff that wasn’t in the movie – but we had to be authentic,” Hope continues.

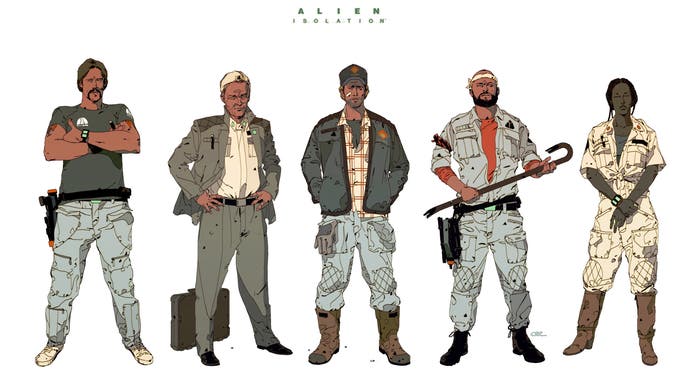

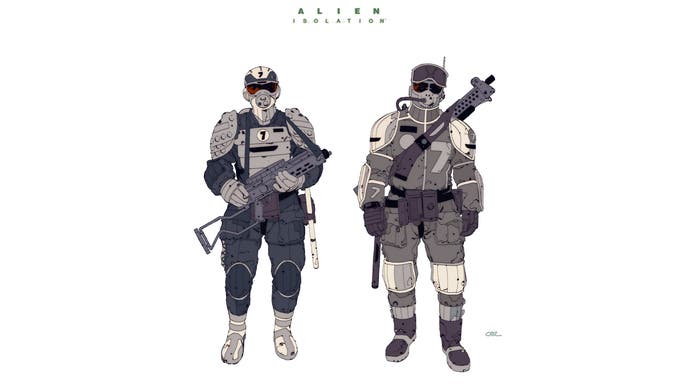

On the hunt for ways to expand and extrapolate, the design team broke down the movie in a phase of ‘deconstruction’, examining the key facets of the film’s aesthetic and using these components as the foundations of Alien: Isolation on which they could build.

“When you look at the sci-fi of the Fifties and Sixties, it’s kind of aspirational, that the future will be amazing,” Hope explains. “Then you had 2001: A Space Odyssey, all sleek designer chairs before the Seventies arrived, and suddenly everyone’s view of the future hit a reality wall. It’s dirty, gritty, and every day is mundane and boring… I didn’t want anyone to run about the game thinking, ‘Okay, I just need to find the space laser because once I find that, I’ll be able to destroy this thing,'” he grins.

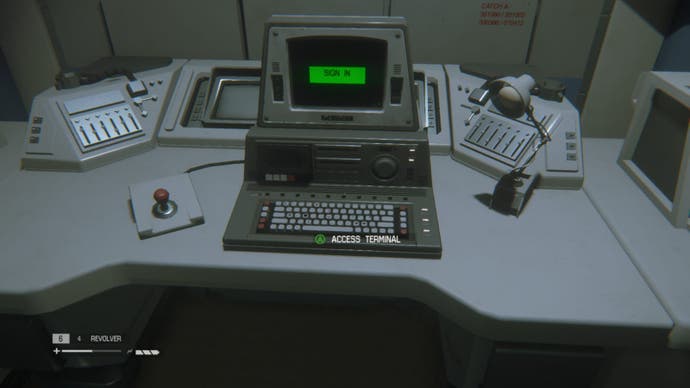

Ironically, the Stanley Kubrick film and its inhuman immaculateness was partially what inspired Ridley Scott to make his own, ultimately gritty sci-fi movie. But it’s this ethic that runs through Alien’s tech: rugged, industrial and unreliable. A far cry from the clean computers and monitors of some of its contemporaries like Star Trek: The Motion Picture, released in cinemas a few months after Alien.

Access to 20th Century Fox’s archives – “around three terabytes of behind-the-scenes archive material from the first movie” – allowed Hope and his team to study Alien in more depth than ever before. But still Creative Assembly needed more material, more connection to the film. It was time to break that 116-minute rule.

“So, yeah, I was breaking my own rule,” admits Hope. Amanda Ripley, after all, was first mentioned in Aliens’ Special Edition. “I was thinking, they’ll never let us have Amanda. But they did – they let us tell her story.”

“In a lot of blockbuster games, it’s all about you rising to the top of the food chain and becoming the ultimate badass. In Alien: Isolation, you’re cowering in the dirt.”

Amanda Ripley follows in her mother’s footsteps, working in space for Weyland-Yutani. She’s busy welding when company man/android Samuels sidles in, offering Ripley some much-needed closure. A small spaceship, the Aniesidora, has located the Nostromo’s log and is en route to the space station Sevastopol. This is the ideal chance for Ripley to discover what happened to her mother, and hopefully close an open chapter of her life. On arrival, an explosion rocks the station, thrusting Ripley into a nightmare. One where crucially – and just like the player – she has no idea what’s going on.

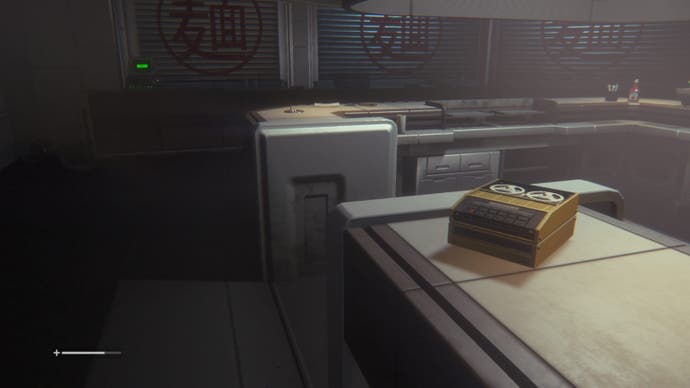

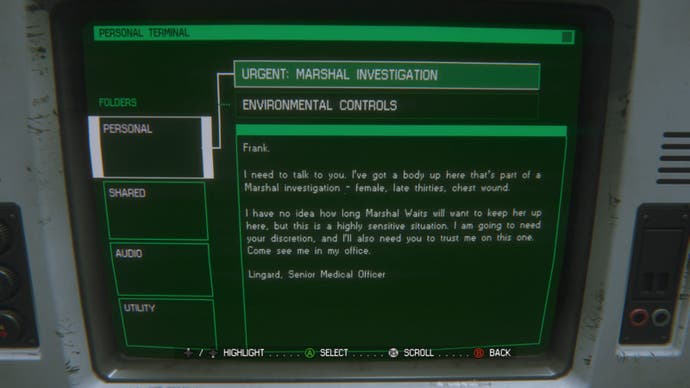

This is the delight of Alien: Isolation. Looking back at it today, at 10 years old, on the surface it seems almost strange: a game where you spend half your time cowering under desks or crammed into lockers. But then Sevastopol’s story is teased out – through environments and props, expressions of the world and its story as one – with the main plot bolstered by little asides and vignettes that flesh out the background of the doomed station. Finding one of those glowing retro tape machines was a thrill, as you wondered what the next breathless and terrified voice had to say. Or maybe they’d be exasperated at the bureaucracy of Sevastopol’s owners, the pound-shop Weyland-Yutani corporation, Seegson. Archive logs, filed away inside Sevastolink terminals, reveal the inner workings of a company gone rotten as much as the panic induced by a lone alien, a perfect killing organism, stalking the rooms, ducts and corridors of Sevastopol.

The way these stories weave together, revealing the station’s history, is almost as thrilling for me as hiding in a locker. Alien: Isolation’s marketing department even created a Twitter account for a systems archivist on Sevastopol. Mike Tanaka’s early tweets hint at the forthcoming violent events on the station. “So…a few more faces popped up on the missing person’s board today. Saw it on my way back to my room. What the hell is going on?”

Like most modern games, Alien: Isolation’s credits include dozens of artists, programmers and designers under Hope’s direction. But there were only three writers. “We spent a lot of time thinking, ‘How do we tell something new with Alien? How do we put a twist on it?'” says Dion Lay, one-third of that writing team. “Then, what became obvious when Dan [Abnett] wrote his draft was actually we didn’t need a twist. We needed to revisit the original, be faithful to it and trust the aliens enough.”

Alongside his colleagues – Abnett, a writer of Warhammer 40k’s Horus Heresy books, comics and the first two Guardians of the Galaxy films; and Will Porter, of Project Zomboid, Observation and No Man’s Sky – Lay absorbed every iota of Alien lore, from comics to novelisations, all filtered back through the lens of the first film. “Y’know, we couldn’t have people running around screaming ‘It’s coming, it’s coming!'” grins Lay. “Because that just wasn’t the vibe. It was more, to quote a Working Joe: ‘You shouldn’t be here'”.

Those low-cost androids pop up regularly throughout Alien: Isolation’s first half, symptomatic of a corporation doing things on the cheap. From the very first log, gleaned from a computer on board the Torrens, the starship escorting Ripley to her destination, the player gets an idea of what to expect. “Sevastopol Station – what a shithole,” reports Blane, a friend of the Torrens’s captain. There’s worse to come: the sad story of Chief Porter (whose name and ID card pic came from writer Will) is one of the first Ripley encounters. “So boys and girls, you’ve probably heard the whispers about Sevastopol by now and I can confirm it’s official. Sevastopol is being decommissioned.”

Chief Porter’s lament interweaves with several stories from other Sevastopol workers and executives. As the real Porter explains, “We were working from a hugely detailed timeline, that itemised everything from the birth of Ellen Ripley, through the years of the movies, the history of Seegson, the commissioning of Sevastopol, all the way to the destruction of the station.” The writing team used this timeline (nicknamed ‘the spreadsheet of doom’ – one of many such documents) to guide them, ensuring the player discovered them in the correct order and that they adhered to the feel of the Alien universe.

“That was the trickiest thing,” continues Porter. “We had to work out what the player was likely to do, what room they would go to next, what areas they could see, and whether we were revealing anything that gives away the plot. And finally, does it make sense?” With the Spreadsheet of Doom as their bible, every incident and significant event was mapped out month-by-month, year-by-year, with most of the granular moments on Sevastopol also measured by time and exact date.

Between the chills, there’s another layer of subtlety to Alien: Isolation. If you’re the type of player to pause and examine the little details, like, say, wall furniture such as posters, you’ll find nods to something deeper than just fear. “Isolation was an important theme of the game,” notes Lay, “so we put a lot of isolation into the adverts the player encounters, even though some of them are really trivial. But they always make the point that you’re missing something, miles from home. A subtle reminder that you’re on your own, even when they’re trying to sell you something.”

Coming back to Alien: Isolation again today, I’ve developed a new-found appreciation of the work that goes into these little moments of side story – details on people Ripley never, for the most part, even meets. There’s Julia Jones, the journalist charting Sevastopol’s descent into chaos; corporate stooge Ransome, betrayed by the very company he so slavishly follows; chief engineer Porter, murdered by a Working Joe android before he’d had the chance to use his makeshift bolt gun weapon; and, of course, there’s poor Mike Tanaka, family man, part-time doodler and Seegson systems archivist. “It’s happening again, got to go and find out what it is. It’s more screams… I have to see what’s happening. Love you, girls x,” he portentously writes in one of his final tweets.

“It’s extremely special and was a lot of hard work,” recalls Porter of the experience of pulling all that detail together. “And it wasn’t always fun. But we did it, and we created something that did a lot for the franchise, a lot for the fans, and a lot for gamers.” Gamers who, naturally, like nothing better than being stalked by an eight-foot-tall killing machine.

Alien: Isolation has often been referred to as one big boss fight – there’s certainly no doubt that the colossal xenomorph, towering over the player as it thuds around Sevastopol, is the show’s star. If you’ve read any development stories on the game, you’ll have heard about the tiger: Al Hope’s incredibly effective way to get his message across to his team. “I wanted to try and reconfigure how you thought [about the alien] and what your response might be,” he explains.

“So, I proposed the analogy of a tiger being loose in the studio and what you would do. You’d be quiet and try to ensure it doesn’t see you. Hide under a desk. But now you need to get to the fire exit at the other end of the studio – how will you do that? You’d have a peek and try to see where the tiger is before slowly moving from desk to desk. Maybe distract the tiger by throwing something in the other direction?” These tactics will sound familiar. “I said, ‘that’s the game we’re going to make’ – totally believable.”

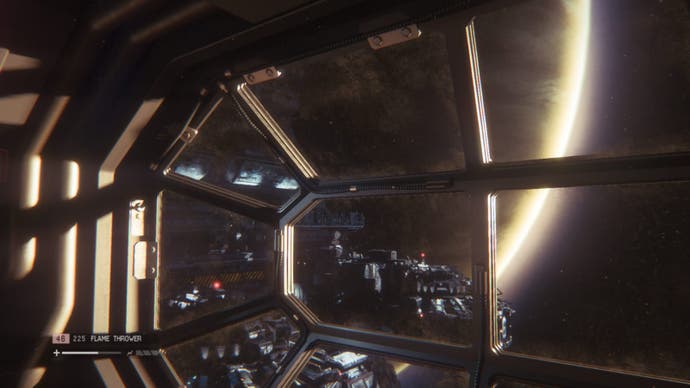

This believability extends to the alien itself. Having discarded any pretence of scripted, choreographed gameplay (save for a handful of instances throughout the game), CA effectively ‘tethered’ the creature to Ripley as she travels around Sevastopol. Any noise, including walking, could attract it, spurring that gut-wrenching clang and thud as it drops down from a vent. Even when Ripley acquires the flamethrower, it’s only ever a deterrent.

“That’s a lovely penny-drop moment when the player uses the flamethrower too often,” Hope explains, in a moment that harkens back to his point about just finding some all-powerful space laser. “For a time, it’s really effective in deterring the alien. But then it starts to learn, and will no longer charge you.” These moments, as the alien stands before Ripley, seemingly unfazed by the weapon in her hands, demonstrate the constantly shifting balance of power in Alien: Isolation. It was also one of the most important balancing acts in the game.

Just over 10 years ago, as features editor of PC Gamer magazine, Andy Kelly watched as one of his colleagues attended Sega’s famous press preview. “Everyone came out of that room terrified and anxious and wrote glowing previews,” he says. “Knowing I was an Alien fan, my colleague returned and said, ‘Dude, this is it. This is the Alien game that someone should have made'”.

Kelly, now author of Perfect Organism, a loving tome dedicated to the game, is perhaps the perfect archetype of an Alien: Isolation fan himself. “The thing I love most about the original Alien is very much the world-building, the sense of place and the incredible production design,” he tells me. “I think Creative Assembly took that to a level not many video games do. It’s also just the best horror game ever made, by quite some margin.”

It’s the excessive dedication to detail – “a lived-in place, with hard-edged functionality, very much mirroring the way that Ron Cobb designed the movie,” as Kelly puts it – that makes this level of superfandom possible. But it’s the prioritising of it – and the authenticity it represents – in the game’s actual storytelling and gameplay design that makes Alien: Isolation truly stand out. “Like Alien, [Alien: Isolation] has the idea of working people being crushed under the boots of these companies just looking out for their own interests,” Kelly says. “It’s the downside of the hyper-commercialisation of space travel and the dangers of these massive monopolistic companies.”

But that authenticity was still a gamble, in one place in particular. “I’ve lost count of how many people who’ve told me they physically can’t play the game because of how relentlessly scary it is,” notes Kelly in Perfect Organism. And he’s right – even a veteran of horror games and movies like myself started Alien: Isolation three times before finally persevering.

“I’ve had a lot of people come up to me and say, ‘I love that game. But I couldn’t play it.’ But that’s the thing – it has to deliver on the scares.”

“We knew it couldn’t be unrelenting pressure – it had to be about tension and release,” Hope explains. “The save stations were part of that mechanism, a moment that lets the player breathe. And of course, it was always the thought of what might happen, or not knowing where the alien was, that’s just as terrifying.” Dynamic music and sound effects, many of them sudden environmental shifts, such as pipes letting off steam, add to the perceived threat, often where there is none.

“In a lot of blockbuster games, it’s all about you rising to the top of the food chain and becoming the ultimate badass,” muses Kelly, coming back to that old point about Aliens and its natural fit for video game action. “Whereas in Alien: Isolation, you’re cowering in the dirt for most of the game. Maybe that was a negative for some people; but obviously, that is what Alien should be about. You should feel like you’re the victim until some great moment in the end when you gather your will and find a way to defeat the Alien.”

Since its release and ensuing accolades, rumours have persisted regarding the next chapter in Amanda Ripley’s life, left teasingly poised at the conclusion of Alien: Isolation. The mobile game Alien: Blackout gave little relief to fans. And it seemed, until today, increasingly unlikely we’d ever see a true sequel or anything like it again. “I find it strange that no one else has tried to do their version of a xenomorph-style adversary,” muses Kelly. “A lot of enemies in horror games are still quite rudimentary in comparison. Maybe it’s hard to do? Or expensive? Or is it that Alien: Isolation ‘only’ sold two million copies?”

I have another theory. Maybe a large faction of gamers thought Alien: Isolation would be too scary for them. I throw this loaded tail barb straight back to Al Hope. “Oh, that’s a good question,” he smiles (that smile takes on a knowing twist now, in light of the surprise news of an Alien: Isolation sequel announced on the anniversary). “You know, I’ve had a lot of people come up to me and say, ‘I love that game. But I couldn’t play it.’ But that’s the thing – it has to deliver on the scares because that’s what we set out to do. It would have broken that idea if we’d altered it and made it less scary. Alien: Isolation asks the question: how are you going to survive? And, yeah, maybe that’s too much for some people. But if it was too easy, it would have broken that spell.”

Today, 7th October 2024, marks 10 years of cowering in lockers and darting under desks for many Alien: Isolation fans. Its influence continues. Alien: Romulus, skittering into cinemas in the UK this past August, offered those eagle-eyed fans a knowing nod, with glimpses of those glowing emergency stations often positioned, as in the game, just in view whenever a significant or dangerous scene was due. It made for a thrilling full-circle moment for Hope and his colleagues.

“You know, in 100 years, when there’s no device available to play Alien: Isolation, that movie will still have those ‘save’ points,” he grins. “We started from an idea and made a game in this universe, and for that to influence a movie – well, I wouldn’t have believed it.”

Having completed Alien: Isolation several times, I thought I’d have a crack at unlocking the ‘One Shot’ achievement on my return, tasking me with completing the game without dying. Even on this latest playthrough, I’m holding my breath as the xeno stomps closer. And I soon make a mistake, those goo-dripping jaws homing in on poor Ripley’s skull once again. Never mind. Hiding in lockers and furtively checking computer screens will forever be my kind of bliss. And now I get to do it all over again.

The Perfect Organism by Andy Kelly is available from Unbound and all good booksellers and is highly recommended. Our thanks to Alistair Hope, Andy Kelly, Will Porter and Dion Lay.