In the history of narco-corruption in Mexico, no higher-ranking official than Genaro García Luna has ever faced justice in the United States.

He’s nowhere near as infamous as Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán, the former Sinaloa cartel leader now serving life in prison. He doesn’t have a nickname or a Netflix series. But according to federal prosecutors, García Luna, Mexico’s former secretary of public security, enabled El Chapo and others to operate with impunity.

On Wednesday, García Luna was sentenced to just over 38 years in federal prison.

The 56-year-old was once his country’s equivalent of J. Edgar Hoover, the square-jawed face of federal law enforcement for nearly a decade. He was a Cabinet-level official tasked with taking on the cartels. And he was a close partner of the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration, which gave him multiple awards over the years to honor his work fighting crime.

At the same time he was receiving DEA accolades, however, he was also leaking secrets to the Sinaloa cartel, which paid him millions of dollars in bribes to ensure protection, according to testimony at his trial last year. He was convicted of conspiring to smuggle cocaine and making false statements to U.S. immigration authorities.

“Although he swore an oath to protect the Mexican people from the scourge of addiction and violence caused by the drug cartels, he was instead a double agent secretly acting to further the Cartel’s interests,” the Eastern District of New York prosecutors said in García Luna’s sentencing memorandum.

In handing down his sentence, U.S. District Judge Brian Cogan called the awards that García Luna boasted of receiving “a smokescreen that allowed you to do illegal things.”

“Sir, you are guilty of these crimes,” Cogan said. “You cannot parade this series of awards… it doesn’t wash, it doesn’t add up.”

Cogan, who also presided over the case of El Chapo, told the former security chief: “You have the same kind of thuggishness as El Chapo, it just manifests itself differently.”

Speaking at the sentencing Wednesday, prosecutor Saritha Komatireddy said of García Luna: “In many ways the defendant is not the same as El Chapo — he’s worse. He enabled El Chapo to exist.”

But while the U.S. Department of Justice has touted García Luna’s conviction and his case has been closely watched in Mexico, there remains a lingering sense of unfinished business.

The DEA’s chief, Anne Milgram, said last year that García Luna’s conviction “should send a clear message — to all political leaders around the world.”

García Luna served from 2006 to 2012 under former Mexican President Felipe Calderón, who launched a bloody military campaign blamed for fracturing some criminal groups while leaving El Chapo’s organization suspiciously intact. Calderón has repeatedly denied any knowledge of corruption in his administration, and no evidence emerged during García Luna’s trial that implicated his ex-boss.

The recent arrest of Ismael “El Mayo” Zambada, a longtime partner of El Chapo known for high-level political connections, has fueled speculation in Mexico that U.S. authorities could be building cases against other top officials or politicians.

During 2019 testimony at El Chapo’s trial, a witness claimed that the Sinaloa cartel delivered a $100-million bribe to Enrique Peña Nieto, the president after Calderón. Peña Nieto denied the allegations, with his chief of staff calling the claim at the time “false, defamatory and absurd.” No smoking gun has surfaced to prove the alleged bribe actually occurred.

And then there is former President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, who left office earlier this month. Allegations that cartel cash helped bankroll his unsuccessful presidential campaign in 2006 initially surfaced during El Chapo’s trial and were raised again during the proceedings against García Luna.

During defense cross-examination, witness Jesus “El Rey” Zambada, brother of El Mayo, denied making any payments directly to López Obrador but acknowledged previously telling U.S. authorities that he gave cash to a lawyer to help fund the 2006 presidential campaign. The testimony was cut short amid objections from the prosecution.

In a handwritten letter sent last month through his lawyer to The Times and other news outlets, García Luna said “it is public knowledge” that López Obrador has ties to “the leaders of drug trafficking and their families.” But he offered no evidence to support his claims, as López Obrador was quick to point out in his public response denying the allegations.

“He writes that there is proof, there are videos, there are calls, there are audios,” the president said of García Luna’s letter during a September news conference. “It’s very simple, he should share them with the public.”

Earlier this year, ProPublica reported that the DEA investigated López Obrador over the campaign allegations, relying on a Mexican lawyer-turned-informant who said he had participated in a meeting at which the alleged payments were first negotiated. The U.S. agents, however, were unable to gather enough evidence to convince prosecutors to bring charges. Justice Department officials were said to express concerns “that even a successful prosecution would be viewed by Mexicans as egregious American meddling in their politics.”

The U.S. ambassador to Mexico during the end of the Calderón era, Earl Anthony Wayne, who testified against García Luna last year, told The Times on Wednesday he believes the U.S. has become more cautious in collaborating with high-level officials, taking steps “to make sure they are willing to be active participants with us in this battle against the criminal groups.”

As for prosecuting a former Mexican president, Wayne said: “That would be a very challenging task to take on,” adding, “I haven’t seen anything that suggests there was suspicion that the very highest-level people were involved in this. It could just be that the connection was at the Garcia Luna level.”

Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum used her regular morning news conference Wednesday to assail the “cynicism” of a letter García Luna sent to the court ahead of his sentencing, criticizing a recent judicial overhaul in Mexico as undemocratic.

“A lot of cynicism, no?” Sheinbaum told reporters. “What moral authority does he have to be speaking about a decision of the people of Mexico?”

García Luna began his career in Mexico’s version of the CIA before climbing the ranks to oversee all federal law enforcement. He has steadfastly maintained his innocence, noting in his jailhouse letter to the press that U.S. investigators were unable to find “a single peso-dollar” worth of bribe money in his bank accounts. Prosecutors did, however, show the jury evidence of his affinity for Harley Davidson motorcycles and other luxuries, leaving the question of how he was able to afford them unanswered.

Cogan imposed a $2-million fine on García Luna, saying, “I think in all likelihood there’s hidden money out there.”

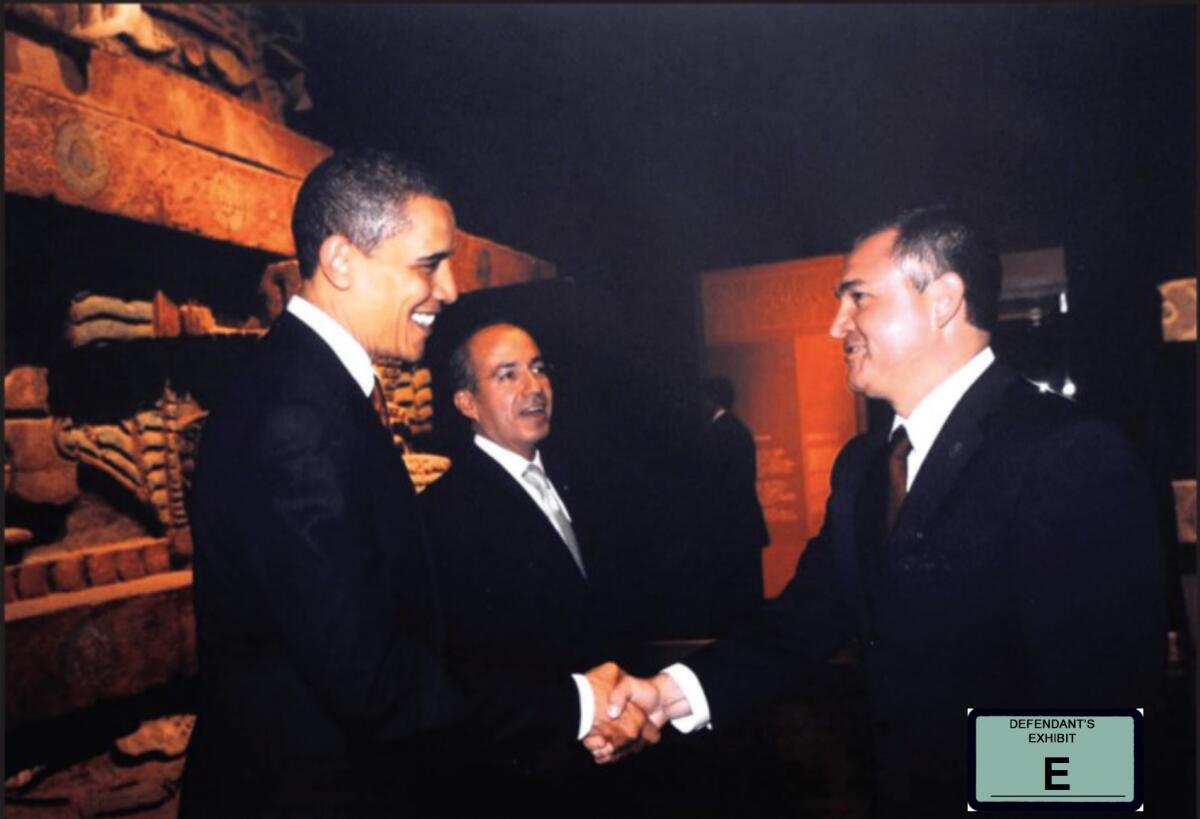

García Luna has also pointed to his meetings with top U.S. officials during the Calderón era, including then-President Obama, arguing that he would not have had such access if under suspicion of corruption at the time.

Genaro García Luna, former secretary of public security of Mexico, met with several high-ranking former U.S. officials, including then-President Obama, shown with former Mexican President Felipe Calderón in the background.

(U.S. vs. Garcia Luna)

Ahead of Wednesday’s sentencing, García Luna’s defense counsel sought to avoid a life sentence by comparing his case to other prominent foreign officials convicted of narco-corruption. The list includes Manuel Noriega, the former de facto head of state in Panama who was sentenced to 40 years for colluding with Pablo Escobar’s Medellín cartel in the 1980s, and Juan Orlando Hernandez, the ex-president of Honduras who in June was handed 45 years for state-sanctioned cocaine trafficking.

While not conceding guilt, García Luna’s court-appointed lawyer, Cesár de Castro, argued his client’s case was more in line with a top Honduran police official under Hernandez and other cases in which defendants took orders from crooked presidents.

“Critically, most high-ranking law enforcement officials sentenced for facilitating large scale drug trafficking were also responsible for conduct much more egregious than the conduct that Mr. Garcia Luna is being held accountable for, yet they all received sentences of less than 22 years,” the defense wrote in a sentencing memo.

Prosecutors, however, reminded the court in their own sentencing memo that one senior cartel member testified that García Luna allowed them to “go around freely … set up and take down checkpoints however we wanted to, whenever we wanted to.” According to trial testimony, the prosecutors noted, García Luna once plotted to return over $1 billion worth of seized cocaine to the cartel.

“He did all this while knowing that thousands of Americans and Mexicans were dying from drug overdoses and cartel-related violence, and he bears responsibility for those deaths,” prosecutors said in their memo.

In seeking life, prosecutors also noted that, “unlike some members of drug trafficking conspiracies who are often recruited in Mexico under difficult personal and financial situations,” García Luna had “a stable upbringing,” before obtaining a college degree and “rising to the top of Mexican society.”

“Simply put, the defendant chose greed and corruption over the well-being of the citizens of Mexico and the United States,” prosecutors said.

García Luna sent a letter to the court ahead of his sentencing, asking the judge for mercy while denying any wrongdoing. He blamed “false information provided by the current government of Mexico,” and “powerful political interests” for his downfall, along with “criminal witnesses” who testified against him. He reiterated those defenses at the sentencing Wednesday.

Previous U.S. efforts to bring elites from Mexican society to justice have not always been successful. In October 2020, roughly a year after García Luna was arrested in Dallas, DEA agents detained Mexico’s former defense minister, Gen. Salvador Cienfuegos Zepeda, on charges he took bribes from cartel traffickers. But under pressure from Mexico and López Obrador, the general’s case was dismissed and he was allowed to return to Mexico.

Komatireddy said García Luna’s sentence sends “a message to all those who have not been caught or are contemplating this behavior. People are watching.”

She said his case is one of the few against high-ranking officials, “not because he’s the first or will be the last,” to engage in corruption, but because it’s “extraordinarily difficult to bring cases like that.”

This summer, U.S. authorities landed one of their most prized catches yet: “El Mayo” Zambada, reputed leader of one of the Sinaloa cartel’s most powerful factions. Zambada, 76, claims he was kidnapped by one of El Chapo’s sons and flown across the border to a small airport near El Paso, where both men were arrested in late July.

Mexican authorities have accused El Chapo’s son, Joaquín Guzmán López, of plotting with his brother already in U.S. custody to hand over Zambada and cooperate in an effort to secure leniency in their own cases. A lawyer for the brothers has denied they cut any deal, but told the Chicago Sun-Times after a court hearing last month: “It’s not easy living in Sinaloa as a fugitive. So sometimes it’s better to get your legal issues resolved.”

Zambada has pleaded not guilty to an array of drug conspiracy and money laundering charges. His case remains in the early stages, but already it has led to disclosures about his dealings with Mexican officials. In a statement from jail sent to The Times and other news outlets, Zambada said he was ambushed in Sinaloa after arriving at a meeting where he expected to find the state’s governor, Ruben Rocha Moya, and another prominent politician, Hector Melesio Cuén Ojeda, who turned up shot to death that same day.

Rocha has denied any relationship with Zambada and said he traveled to Los Angeles on the day in question, although several recent media reports have raised questions about whether he actually made the journey.

Zambada said he was summoned to mediate a political dispute between Rocha and Cuén. The kingpin said he traveled to the meeting with a commander in the State Judicial Police of Sinaloa who served as his bodyguard and “who no one has seen or heard from since.” Sinaloa authorities subsequently confirmed the police official, José Rosario Heras López, was active with the police agency and remains missing.

Zambada is scheduled to make his first appearance before Cogan in Brooklyn on Friday.

Times staff writer Patrick J. McDonnell contributed reporting from Mexico.