On October 19, 1980, the Amalgamated Clothing and Textile Workers Union (ACTWU) forced the textile company JP Stevens to sign a contract for the first time in North Carolina and Alabama. The result of years of struggle, this was a groundbreaking agreement in one of the most anti-union bastions in the United States. Unfortunately, it only lasted a few years before the apparel industry moved to non-union labor overseas. But you know this victory, if you’ve seen Norma Rae.

The apparel industry has pioneered labor exploitation strategies since the dawn of the Industrial Revolution. While there were early attempts at treating workers with respect, this collapsed very quickly, with increasingly cheap labor becoming the norm. As new waves of immigrants came to the Northeast, they entered the sweatshops and factories. And when they won reforms after 146 of them died at Triangle, the companies started to move to the southern Piedmont, where they would have no immigrants, no socialists, and a long history of paternalistic political and labor relations that they felt would translate to labor peace.

Northern-based textile unions had tried organizing the South through the 20th century. Southern state governments and mill owners responded with brute force. The 1929 strike led to horrific violence. The 1934 strike was a last-ditch effort by the United Textile Workers to survive, and its brief success in organizing some Southern mills was no match for state violence. After World War II, state violence was harder to pull off, but the paternalism of Southern mill towns still made them a very tough nut to crack. The Textile Workers Union of America (TWUA) started its organizing campaign in the South all the way back in 1963. At that time, the unionization rate in Southern textiles was only about 10 percent. The campaign took 17 years to win, an eternity in this industry.

Key to that victory was the 1975 merger of the small TWUA with the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America, becoming the ACTWU and giving it the resources to fight the companies effectively. There is something of a fetish on the labor Left in this country around small grassroots unions that supposedly lead to greater democracy, but these small organizations simply don’t have the resources to fight multinational corporations. You have to have real resources to win a union campaign and that’s what the ACTWU provided. They needed the help too. JP Stevens was an awful company. It routinely broke labor law, was brought before the National Labor Relations Board and fined, and did the same thing over and over again. Between 1963 and 1973, the company faced 22 cases before the National Labor Relations Board and lost 21 of them. In 1974, its workers in Roanoke Rapids, North Carolina, voted for a union. It took Stevens six years to finally agree to a contract.

The ACTWU also helped pioneer the corporate campaign that became a key part of labor struggles in the 1980s. The union started this in 1976 with the labor organizer and strategist Ray Rogers. A corporate campaign takes a broad look at a company’s products and platforms and attempts to nationalize or internationalize a strike that may be in an obscure place by creating public attacks on the company for its unfair labor practices and unwillingness to negotiate fairly. They targeted banks and insurance companies who did business with JP Stevens to withdraw that business. They developed slates to run for the boards of publicly traded companies. The ACTWU also began to use its own financial power, pulling union pension funds from companies that continued to do business with Stevens. This started having a real impact by 1978, when Stevens executives were forced off the board of banks and other executives began resigning from Stevens’ board. The corporate campaign was critical in finally forcing the company to an agreement.

But of course the real key in winning the union was the workers themselves. This largely female workforce had a lot to overcome. That included racial division. By the 1970s, this was an integrated workplace, but there was a lot of racial tension. Support for the union was higher among African-Americans than whites. There were also gendered tensions, as male workers were often uncomfortable with the leading role women played in the strike. And in fact, this was a strike largely led by Black women.

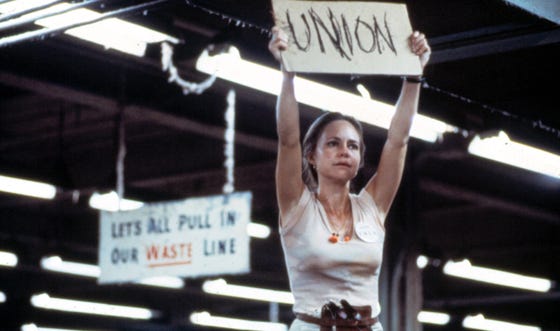

This strike became famous because of the 1979 film Norma Rae, where Sally Field played a lightly fictionalized version of strike leader Crystal Lee Sutton. Although perhaps slightly ham-fisted at times in terms of the relationship between the organizer and Norma, the film does perhaps a better job than nearly every other in film history at demonstrating the struggle of organizing in a realistic way without trying to turn the lead character into a revolutionary heroine. Sutton and the union organizers were a bit upset with the film for relying so much on her sexuality, which was a major issue in the strike itself, with evangelical workers disliking her for not marrying the father of her second son. But I find it worth watching today and sometimes use it for students, who generally seem to like it alright. One weakness is that it does downplay the role of Black unionists. They are in the movie, although all men as I recall, but they are much more in the backseat than they were in the strike itself.

Finally, in 1980, the combination of the continued agitation of workers, the corporate campaign, and the film forced JP Stevens to sign a contract that covered its Roanoke Rapids mill and its Montgomery, Alabama, mill. The company also agreed to bring into contract any mill the union organized in the next 18 months. But the fight was not over. In 1982, Stevens closed the Montgomery mill. The workers received severance pay thanks to the union, but that wasn’t much. In the five years after the contract was signed, facing the newly globalized apparel industry and the closure of plants across the nation, the ACTWU lost more than 50,000 members. None of this had anything to do with the union contract, but rather reflected larger shifts in American capitalism away from investment in American factories and toward global labor exploitation. The Roanoke Rapids mill was one of the last to close entirely, not until 2003, although by that time it only employed 300 people. Many of the organizers of the mills, including Sutton, went on to organize other worksites, attempting to unionize the South, which remains the most difficult place to win a union election to the present.

Meanwhile, the apparel industry still murders its largely female workforce across the world today.

FURTHER READING:

Timothy Minchin, Empty Mills: The Fight against Imports and the Decline of the U.S. Textile Industry

Aimee Loiselle, Beyond Norma Rae: How Puerto Rican and Southern White Women Fought for a Place in the American Working Class

Jefferson Cowie, Stayin’ Alive: The 1970s and the Last Days of the Working Class

The preceding links give Wonkette a small commission!