For 800 years he was the stuff of Norse legend.

Now scientists say skeletal remains found in a well at Norway’s Sverresborg castle are those of the mysterious figure mentioned in a medieval saga.

The new findings, published in the journal iScience on Friday, used advanced DNA analysis to connect the identity of the remains to a passage in a centuries-old Norse text called the Sverris Saga. It’s a compilation of different sources describing the internal political struggle, or civil war, in medieval Norway from 1130 to 1217.

The saga, named after Norwegian king Sverre Sigurdsson, describes the political conflict between the king and his chief enemy, the archbishop of Nidaros, Eysteinn Erlendsson.

According to the saga, the body of a dead man — later referred to as “Well-man” — was thrown down a well during a 1197 military attack aimed at poisoning the main water source for locals.

Little else is mentioned in the saga about the Well-man or who he was.

Researchers are often skeptical of the historical accuracy of events described in such tales, said research project lead Mike Martin, a professor at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology.

“The sagas are a mix of historical fact, storytelling, political propaganda, and Old Norse religion,” he said in an email Monday.

The Sverris Saga is, however, considered one of the most reliable historical sources, as it was written down during and immediately after the period of political unrest, said Stefan Brink of the department of Anglo-Saxon, Norse and Celtic at the University of Cambridge in England. He was not involved in the research.

King Sverre of Norway personally provided information to the writer, Icelandic abbot Karl Jónsson, and instructed him on the details of the saga, Brink added. “If one would anticipate to finding historical accuracy in some sagas, Sverris Saga would be the best contender.”

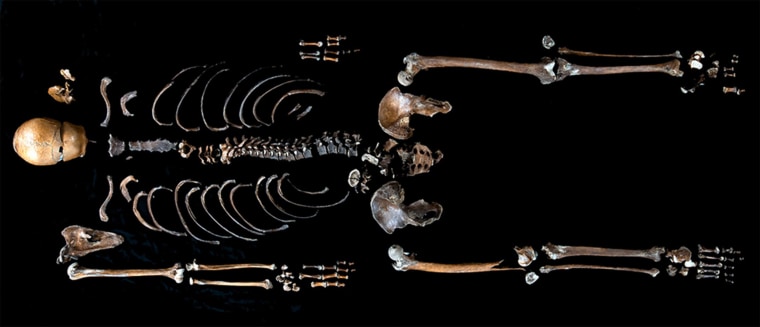

The skeletal remains were first discovered in the castle’s well during restoration work in 1938, though researchers at the time could conduct only a visual examination because of the start of World War II.

The remains stayed in the well for 80 more years until the excavation began in 2014, led by Anna Petersén of the Norwegian Institute of Cultural Heritage Research in Oslo.

By 2016, the full skeleton was retrieved from the well at Sverresborg in Trondheim in central Norway.

Recent scientific developments provide a variety of advanced methods to analyze skeletal remains in greater detail, such as genetic sequencing and radiocarbon dating.

Human genomes are around 99.6% percent identical, according to the National Institutes of Health, with genetic variation accounting for just 0.4%.

The team identified the genomic variation by extracting DNA from the Well-man’s mandible, the lower part of the jaw.

“During the Covid-19 pandemic we obtained access to the teeth, which really accelerated the study,” Martin said. It took around six years to complete in total.

The genetic research could provide an opportunity to gain a deeper understanding of remains previous archaeological excavations have uncovered, experts say.

“The project shows how important science, archaeology and the collaboration between archaeology and history have become in today’s research, which very often comes up with sensational results, as this one,” Brink said.

Advancements in technology also allow skeletal remains to be linked to characters from Norse sagas, blurring the lines between legendary myths and historical facts.

And it is not the first instance of a saga character’s skeletal remains’ being found.

Elizabeth Rowe, a professor of Scandinavian history at the University of Cambridge in England, highlighted research published in 1995 by Jesse L. Byock making a compelling case for the identification of the remains of Egill Skallagrímsson, a 10th century Icelandic poet whose story is told in a 13th century saga, the Egils saga.