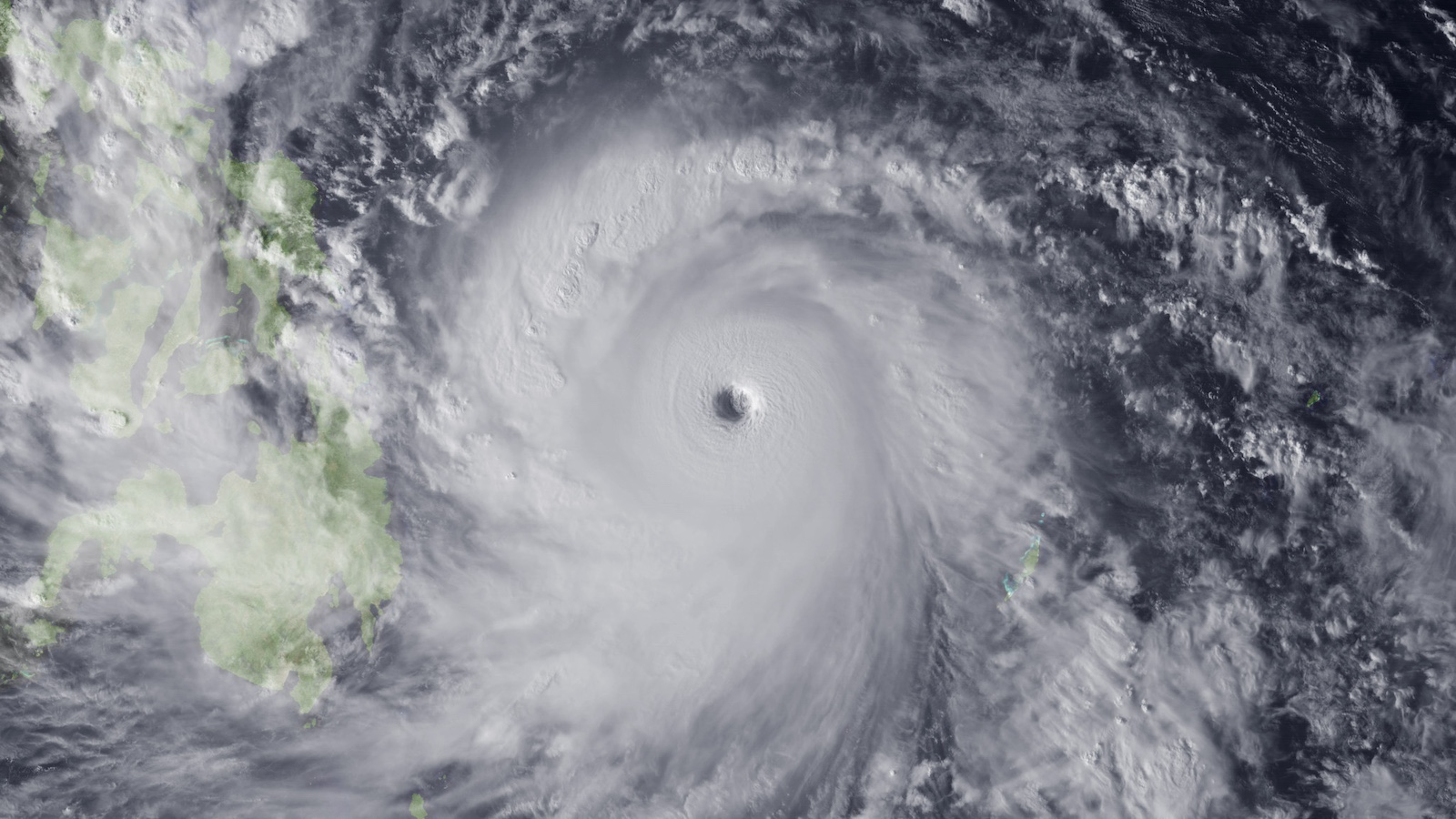

In November 2013, one of the strongest tropical cyclones in history made landfall in the Philippines. Known locally as Super Typhoon Yolanda, the storm pummeled the island country with 235-mile-per-hour gusts and a 17-foot storm surge; picked up limousine-sized boulders as easily as plastic bottles and deposited them hundreds of feet away; and officially killed 6,300 people, although the true death toll was likely much higher.

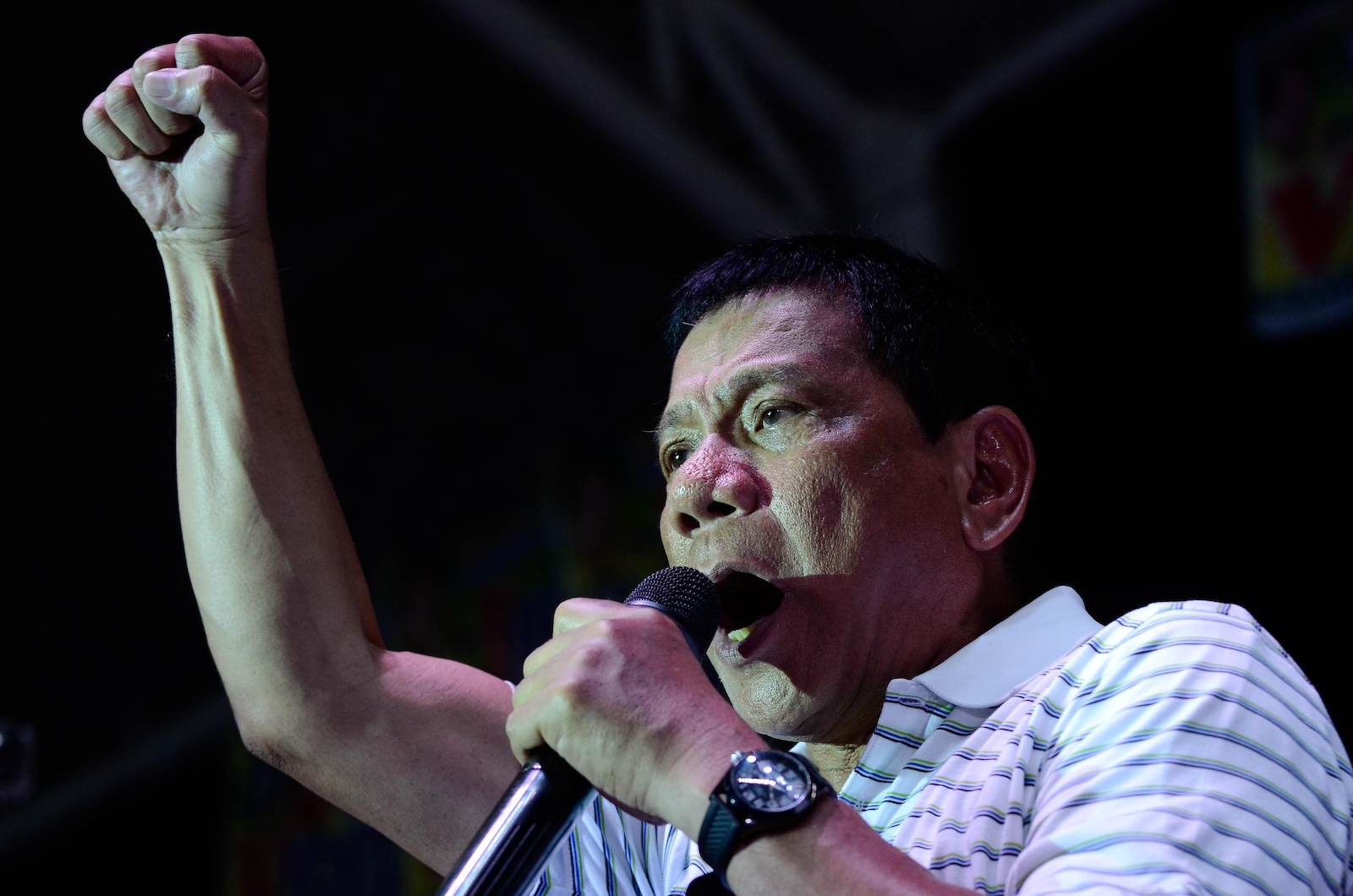

Rodrigo Duterte, then the longtime mayor of Davao City, made headlines for traveling some 400 miles to one of the worst-ravaged areas of the country, along with a convoy of medical and relief workers and roughly $150,000 in cash. He announced that he’d told security forces to shoot any looters who might try to intercept the convoy. (He went on to clarify, “I told them to just shoot at the feet. … They can have prosthetics after, anyway.”) As a presidential candidate in 2016, Duterte slammed his opponent, the former interior secretary, for allegedly misspending Yolanda recovery funds. He won in a landslide.

Over the next six years, Duterte proved that his foul-mouthed maverick shtick wasn’t harmless posturing. He presided over a brutal war on drugs in which police and vigilantes — emboldened by the president — killed as many as 30,000 people, imposed martial law on an island home to 22 million for two and a half years, and signed a law that gave law enforcement broad authority to arrest and detain suspects without warrants.

Typhoon Yolanda “offered the Philippines’ presidential hopeful Rodrigo Duterte an avenue to exploit people’s helplessness to secure their support,” according to an economist who studies the ways storms affect democracy.

The past decade or so has given rise to a grim parade of Duterte-like candidates around the world — politicians who have obliterated the bounds of acceptable political discourse, scapegoated religious and ethnic minorities, dismissed journalism as fake news, sought to imprison their rivals, and undermined democratic checks and balances. In India, commonly referred to as “the world’s largest democracy,” Prime Minister Narendra Modi has vilified Muslims and carried out a campaign promise to build a Hindu temple on the site of a mosque razed by Hindu mobs. In Brazil, former President Jair Bolsonaro promoted a bill that would strip Indigenous tribes of control of their lands and unsuccessfully plotted a coup to remain in power after losing reelection. And in the United States, former President Donald Trump — currently running for reelection — separated immigrant children from their parents and incited a horde of supporters to attack the U.S. Capitol.

Dondi Tawatao / Getty Images

None of these candidates rose to power after a natural disaster quite as singular as Typhoon Yolanda, but they’ve advanced at a time when climate change has become increasingly visible and harmful as worsening storms, droughts, and wildfires affect more and more people. This might not be a coincidence. Although it’s difficult to prove that climate change contributed to the ascent of these strongmen, political scientists, economists, and psychologists have found evidence that the dangers of global warming can push individuals, and nations, in an authoritarian direction.

Faced with the threat of climate change, “most people can’t build bunkers in, you know, Hawai‘i or what have you,” said James McCarthy, a professor of economics, technology, and environment at Clark University in Massachusetts. “But they can vote for people who will promise to put their national interests and their economic interests above everything else in the world — and who will promise to try to secure a future that looks a lot like the past.”

Researchers have long noticed that natural disasters like floods, droughts, and wildfires can help autocratic politicians consolidate power. (There’s significant overlap between autocracies — systems in which a single leader holds absolute power — and authoritarian regimes, which are characterized by unconstrained central power and limited human and political rights.) In the 1930s, for instance, a hurricane that hit the Dominican Republic less than a month into the presidency of Rafael Trujillo gave Trujillo an opening to declare martial law, eliminate the political opposition, and erect monuments in his own honor.

Political scientists have theorized that, in the face of physical, economic, and social vulnerability, voters seek safety in the form of leaders who promise to take decisive action to deliver relief. One study of elections in India found that voters punish incumbents when it floods — unless the incumbents respond vigorously to the disaster.

Until fairly recently, researchers looking at the ties between climate disasters and authoritarianism only had case studies, like Duterte and Trujillo. There’s always a complex tangle of conditions leading to any particular leader’s advancement — for instance, the Philippines had a long history of dictatorship before Duterte came along — which means that case studies can show only a correlation between disasters and the erosion of democracy. But in 2022, economists in the United Kingdom and Australia devised a clever study seeking to prove that storms like hurricanes actually cause a slide toward authoritarianism.

The economists behind the study chose to look at island countries, because they presented an opportunity for a “natural experiment.” Although climate change is making tropical cyclones more intense on average, any individual storm’s severity is random, as is its timing. Storms also tend to affect an entire island nation instead of just one region. These observations mean that any variation in democratic conditions following a storm can reasonably be attributed to the storm.

Island countries that don’t tend to get big, destructive storms, like Iceland and Singapore, served as a control group in the study. Comparing storm data to a dataset measuring democracy and autocracy in island countries between 1950 and 2020, the authors found that storms reduce these countries’ democracy scores by an average of 4.25 percent in the following year. They dubbed island countries that have experienced persistent dictatorships “storm autocracies” and predicted that autocracy “could increase over time” as climate change makes catastrophes more likely.

NOAA via Getty Images

Habib Rahman, an economics professor at Durham University Business School in the United Kingdom and the lead author of the study, told Grist that he and his co-authors believe theirs is the first paper that draws a causal connection between natural disasters and autocratic leadership. “Our paper really tried to fill the void here,” Rahman said.

A causal relationship between climate change and authoritarian attitudes has also been demonstrated on a much smaller scale in psychology studies. In 2012, a team of psychologists divided cohorts of German and British university students into two groups and told them they were helping to develop a knowledge test. They informed half of the volunteers about some of the threats associated with climate change — findings about how hazardous heat, wildfires, and glacier loss are projected to worsen in the future. The other half learned “neutral facts” about their respective countries’ weather, forests, and economies, with no mention of climate change. The volunteers who had been told about the perils of climate change expressed more negative opinions of dangerous or marginalized groups — like terrorists, drug addicts, or attack-dog breeders — on a 10-point scale measuring their attitudes toward various demographics.

Similar experiments have found that exposure to threatening information about climate change increases people’s conformity to collective norms, racism, and ethnocentrism — in short, that it pushes people to identify with groups that they belong to and denigrate groups that they don’t belong to. A recent survey of some 1,700 white Britons found that participants who were exposed to threatening information about climate change, and who felt that their country was unlikely to tackle climate change, had more negative feelings about Muslims and Pakistanis than a control group primed with neutral facts.

Experts acknowledge that the effects demonstrated in these studies were small, and they haven’t been consistently replicated with different groups of participants. Being exposed to information about climate change affected participants’ opinions of certain out-groups, but not others. What’s more, people’s response to a survey does not necessarily predict how they’ll behave at the ballot box — where millions channel their fear of climate change into a vote against authoritarian candidates, not for them. But Immo Fritsche, a social psychology professor at Leipzig University in Germany and a co-author of three of these psychology studies, still thinks this body of research sheds light on the psychological impacts of a changing climate. “I think this is an important addition we can contribute on the ground of what we know about the subtle consequences of threat for human thinking, the sense of a kind of catalyzing process,” said Fritsche.

The 2022 storm autocracies study and Fritsche’s psychological studies all included control groups to demonstrate cause and effect. Unfortunately, there is no second planet Earth unaffected by climate change to serve as a control group for the broader question of whether climate change is enabling authoritarianism around the world.

Still, McCarthy, who edited a special issue of the Annals of the American Association of Geographers on authoritarianism, populism, and the environment in 2019, thinks the alarming proliferation of dictators and aspiring dictators in recent years shows that it’s a hypothesis worth taking seriously. “I think you have accelerating climate change contributing incredibly strongly to a growing sense of insecurity and inequality: fear about the future, fears that the future is going to be less stable and secure than the past, fears that the world is increasingly going to be divided into winners and losers, and you can’t trust society or collective institutions,” he said. In response to these fears, people understandably want to secure their own safety. “In that context, I think that the appeal of the strongman who promises simple answers to complicated things actually makes a lot of sense.”

McCarthy believes this is true even though supporters of many strongmen — including a third of Americans who voted for Trump in 2020 — deny that climate change is real. “I think that people are reacting to manifestations of climate change or effects of climate change without always or often recognizing them as such,” he said. For instance, millions of Americans in recent years have experienced wildfires, power outages, and a rise in insurance rates — events that affect their daily lives, and their political thinking, whether or not they consciously attribute them to climate change. It’s worth noting, however, that a number of far-right political parties in Europe do acknowledge climate change — and promote a crackdown on immigration as a solution.

“I think that the appeal of the strongman who promises simple answers to complicated things actually makes a lot of sense.”

– James McCarthy, professor of economics, technology, and environment at Clark University

Some academics have warned that authoritarian states, unconstrained as they are by human rights concerns and democratic oversight, might genuinely be better positioned than liberal democracies to respond decisively to the threats associated with climate change. China, for instance, has installed more renewable energy than any other country — but it’s done so by using forced labor and quashing any dissent that might slow down green development.

Saving liberal democracy, then, might be a question of proving that it can rise to the occasion. In the U.S., some pundits have argued that abolishing the filibuster to make the Senate more democratic, eliminating the debt ceiling to allow for ambitious climate spending, and passing federal legislation to bolster voting rights across the country would go a long way toward defanging authoritarian trends in the U.S. Others have argued for higher taxes on the wealthy, to help address the feelings of worsening inequality that drive some voters toward populist, strongman candidates.

Climate activism could also harness people’s tendency to identify with an in-group when faced with the threats associated with climate change — an in-group defined by shared values like social justice and care for the environment, instead of by nationality, race, or religion. “If it’s true that threatening climate change increases collective thinking and acting,” said Fritsche, then it’s possible “that under the conditions of threatening climate change, people become more willing to join collective action for the climate, for environmental protection, if they conceive of this as being normative for their group, for their nation, for their generation.”

McCarthy urged people who are concerned about both climate change and authoritarianism to resist the urge to see the erosion of democracy as an inevitability as the Earth gets hotter and hotter. “Doomerism and nihilism is a terrible direction politically. It’s obviously a self-fulfilling position,” he said. “However dire our politics, and however difficult things look at the moment, politics is ultimately about what people decide to do together.”

“The future is not written,” he added. “It’s what we make it.”