Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it’s investigating the financials of Elon Musk’s pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, ‘The A Word’, which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.

Mysterious sounds emanating from the depths of the Southern Ocean continue to astound scientists as the latest research suggests the strange noises may have been a “conversation” between unidentified animals.

The recording was made by New Zealand scientists in the early 1980s and contains four strange, short tones. Ten years ago, scientists said they had found evidence that the ounds were made by Antarctic minke whiles. Now, the Acoustical Society of America has called the researchers’ findings into question. But, if not minkes, then what are they? And, what are they talking about?

“Maybe they were talking about dinner, maybe it was parents talking to children, or maybe they were simply commenting on that crazy ship that kept going back and forth towing that long string behind it,” British Columbian University of Victoria researcher Ross Chapman said Thursday.

The bursts of sound resemble quacks, earning the recording the nickname “Bio-Duck.” Speculation about their source was varied. It could be an underwater submarine, or a fish.

Research from NOAA, Duke University, and other groups attached suction cup tags and microphones to minkes and were able to identify “Bio-Duck” calls that were distinct. Minkes produce bizarre “boinging” sounds, and others like those heard in the “Bio-Duck” recording. Before it was released, no one had thought the whales were in the area during the winter, as they had been known to migrate to warmer waters. Recent research shows that minkes are socially flexible, with larger and older individuals more likely to socialize than smaller and younger whiles.

“However, the sounds have never been conclusively identified. There are theories the sounds were made by Antarctic minke whales, since the sounds were also recorded in Antarctic waters in later years, but there was no independent evidence from visual sightings of the whales making the sounds in the New Zealand data,” the society said Thursday.

The Independent’s request for comment from the lead author of the 2014 findings was not immediately returned.

Now, Chapman says, there is further evidence that the work was a conversation between multiple animals. He presented his work at the virtual 187th Meeting of the Acoustical Society of America.

Chapman helped to analyze the data from the recordings in the 1980s and discovered the data contained a “gold mine” of information about many kinds of sound in the ocean, including from marine mammals.

“You have to understand that this type of study of ocean noise was in its infancy in those days. As it turned out, we learned something new about sound in the ocean every day as we looked further into the data — it was really an exciting time for us,” he said.

At first, Chapman added, they couldn’t believe the “Bio-Duck” tones were related to living organisms.

“The sound was so repeatable, we couldn’t believe at first that it was biological,” Chapman said in a statement. “But in talking to other colleagues in Australia about the data, we discovered that a similar sound was heard quite often in other regions around New Zealand and Australia.”

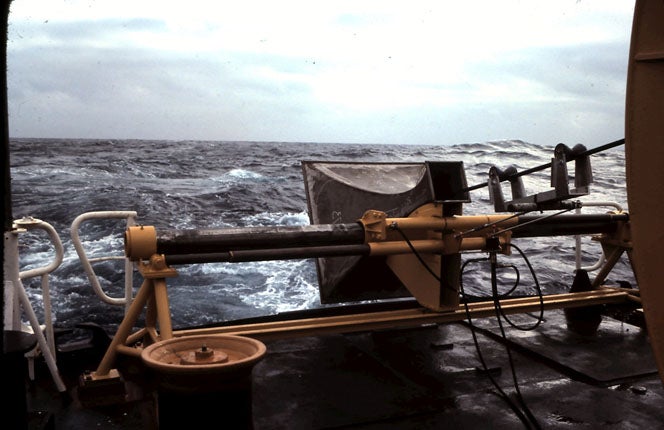

No matter the animal, he believes that the recording could be a conversation because of how the data was recorded. Scientists used an acoustic antenna: a group of underwater devices attached to the back of the ship that detect and record ocean sounds from all directions. The antenna allowed them to figure out where the sounds were coming from.

“We discovered that there were usually several different speakers at different places in the ocean, and all of them making these sounds,” Chapman said. “The most amazing thing was that when one speaker was talking, the others were quiet, as though they were listening. Then the first speaker would stop talking and listen to responses from others.”