Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it’s investigating the financials of Elon Musk’s pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, ‘The A Word’, which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.

An American student analysing publicly available data found a sprawling Mayan city with thousands of undiscovered structures, including pyramids, under a Mexican forest.

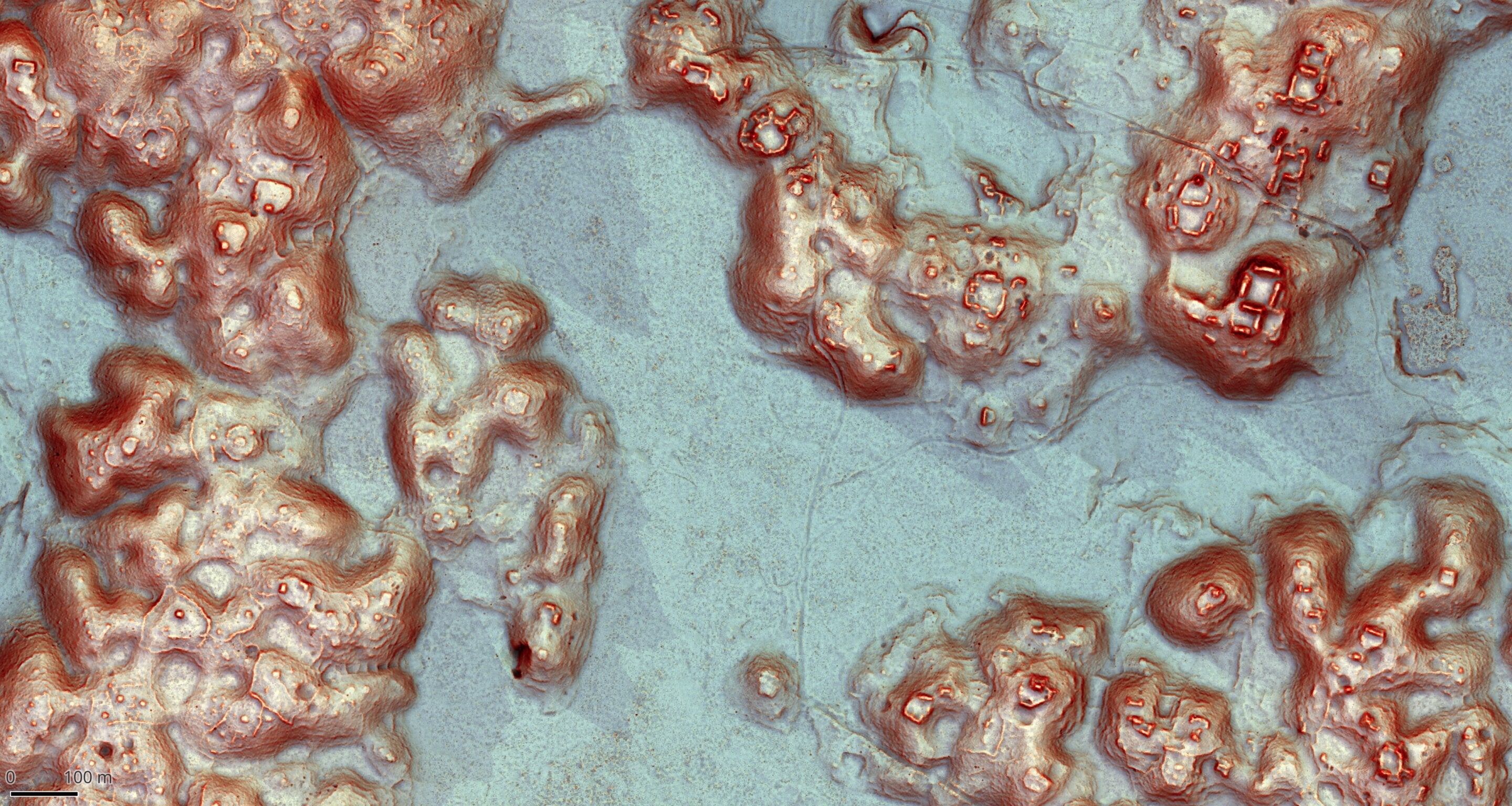

The data came from laser scans of the Campeche region and revealed a buried world, since named “Valeriana”, with nearly 6,700 undiscovered structures.

Archeologists have been using laser scanning lidar technology to assess anomalies in landscapes across the Yucatan peninsula in Central America and stumbling upon pyramids, family houses and other Mayan infrastructure.

For a long time, surveys to find ancient structures sampled just a couple of hundred square kilometres. “That sample was hard won by archaeologists who painstakingly walked over every square metre, hacking away at the vegetation with machetes, to see if they were standing on a pile of rocks that might have been someone’s home 1,500 years ago,” said Luke Auld-Thomas, PhD candidate at the Northern Arizona University who made the discovery.

In recent years, researchers have been analysing data from lidar scans taken for unrelated purposes to look for evidence of Mayan structures.

Mr Auld-Thomas analysed data from one such lidar project from 2013, focused on measuring and monitoring carbon in Mexico’s forests, to see what lay underneath 50 square miles of Campeche. “I was on something like page 16 of Google search and found a laser survey done by a Mexican organisation for environmental monitoring,” he told the BBC.

Analysing the data using modern archaeological methods revealed a dense and diverse array of Mayan settlements, including one sprawling city dating to between 250 to 900AD.

“The government never knew about it, the scientific community never knew about it. That really puts an exclamation point behind the statement that, no, we have not found everything, and yes, there’s a lot more to be discovered,” Mr Auld-Thomas said.

His study was recently published in the journal Antiquity.

The lost city has “all the hallmarks of a Classic Maya political capital”, Mr Auld-Thomas noted. “We did not just find rural areas and smaller settlements. We also found a large city with pyramids right next to the area’s only highway, near a town where people have been actively farming among the ruins for years.”

Studying such ancient cities could help solve modern problems facing urban development, researchers said. “There were cities that were sprawling agricultural patchworks and hyperdense,” Mr Auld-Thomas said. “Given the environmental and social challenges we are facing from rapid population growth, it can only help to study ancient cities and expand our view of what urban living can look like.”