To contend that the indictment of Gautam Adani, his nephew, and their associates, in the United States has dealt a blow to the ambitions of one of India’s, and the world’s, richest men, would be an understatement. The prominent tycoon, whose proximity to Prime Minister Narendra Modi is the stuff of legends, has never before been hurt like this. His reputation is at stake. And with it, his business plans.

The 30,000-word report of the New York-based short-selling firm Hindenburg Research published in January 2023 that claimed that Adani was “pulling the largest con in corporate history”, and innumerable reports by investigative journalists, including ones at the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP), pale into insignificance when compared to the gravity and the depth of the allegations against him, his family members, and others who work closely with them, by two agencies of the federal government of the US: the Department of Justice (DoJ) and the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), the regulator of that country’s financial markets. The allegations are, in turn, largely based on investigations by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI).

Despite the arrest warrant against him, Adani is trying to put up a brave front with the help of his public relations machinery. But he probably realises, as does his patron Modi, that after this round of civil and criminal charges, things can never be the same again. This is simply because no capitalist in India has been so close to the head of the country’s government—the two are like Siamese twins and, hence, the conflation of their surnames in social media as Modani.

India’s politics-business nexus

The nexus between big business and politics is neither new nor unique to India. Here are only two examples from the past from this country. Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi worked out of the home of “nationalist” businessman Ghanshyam Das Birla till January 30, 1948, the day he was assassinated by Nathuram Godse. It is worth reading his own words on why he did so. Dhirubhai Ambani openly supported Indira Gandhi at a public gathering in 1979, when she was out of power. And Pranab Mukherjee was a close friend of the Ambani family. But the association between Modi and Adani is different from the examples cited.

The incumbent Prime Minister has assiduously promoted Adani’s business interests, more than the interests of all other Indian businesspersons put together. This has sometimes worked to the detriment of the country’s interests, for instance, in Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, and Kenya, among other countries. Thus, Modi cannot hope to completely insulate himself from the fallout of the charges of conspiracy and fraud against Adani.

It was afternoon on November 21 in New York and Washington, DC, at a time when Indians were fast asleep, when news broke about the DoJ serving an indictment document (akin to a charge sheet) on the 62-year-old business magnate, his nephew Sagar Adani, their associate Vneet Jaain (all directors in an entity in the sprawling and widely-diversified Adani conglomerate), as well as four others associated with a Canada-based pension fund. Soon afterwards, it was announced that the SEC too had filed civil and criminal complaints against them, a grand jury subpoena (like a summons to appear before a jury in court) had been issued, and, most importantly, a warrant of arrest had been prepared against them.

When India woke up that morning, the stock markets turned jittery. Adani Group shares came down by proportions varying between 7.2 per cent and 22 per cent on the National Stock Exchange (NSE) in the course of the day. There were reactions from around the world. By then, those who had perused the DoJ’s 54-page indictment order and the SEC’s allegations were stunned by the details contained in the two documents that were made public. It was learnt that more than a year and a half earlier, on 17 March 2023, special agents of the FBI had confronted Sagar Adani with a judicially authorised search warrant and had taken custody of his personal electronic devices.

In these devices, they claim to have found, among other things, a list of names of persons and organisations who had been, or had to be, allegedly bribed to clinch power purchase and sale agreements for solar energy in four Indian states and one Union territory: Tamil Nadu, Odisha, Chhattisgarh, Andhra Pradesh, and Jammu and Kashmir. That is not all. It was disclosed that Gautam Adani himself has taken photographs of the search warrant and subpoena documents served on his nephew and emailed these to himself.

Examining the charges

What were the charges? Adani Green Energy and Azure Power had won tenders and obtained contracts to generate solar energy from a public sector company, the Solar Energy Corporation of India (or SECI, not to be confused with the SEC of the US), under the Indian government’s Ministry of New and Renewable Energy. The power was deemed too expensive, and SECI was not finding buyers from among State electricity distribution companies (discoms). Hence the need to pay bribes to ensure that the power generated was actually sold, or so the DoJ has alleged.

According to the department, the total quantum of bribes that were allegedly paid or promised to be paid to “officials” in India was $265 million, or around Rs.2,029 crore at the then prevailing exchange rates. The lion’s share of this amount ($228 million) allegedly went to officials in one State, Andhra Pradesh, then headed by Y.S. Jagan Mohan Reddy, whose name figures in the fine print of the SEC’s documents. Whereas the Yuvajana Sramika Rythu Congress Party (YSRCP) led by Jagan Reddy has predictably denied any wrongdoing, what has been documented is that before the State government signed a deal to purchase the power, Gautam Adani had personally met Jagan Reddy in August 2021 and Sagar Adani had met him the following month.

Andhra Pradesh Chief Minister Y.S. Jagan Mohan Reddy interacting with Adani Group chairman Gautam Adani at the World Economic Forum at Davos in Switzerland on May 22, 2022.

| Photo Credit:

HANDOUT

What has also been claimed is something unprecedented and astounding: the amounts that were promised as bribes were calculated on the basis of each megawatt (MW) of electricity purchased. One claim is that the rate was Rs.1,750 crore per MW.

Why were these four States and one UT selected? At the time the bribes were allegedly paid or promised to be paid, the ruling party at the Centre, the BJP, was not controlling the governments in any of the four States. The party’s nominee was, however, heading the Jammu and Kashmir government. Could it be that officials in BJP-ruled States did not need to be bribed? That just a nod from New Delhi would suffice for an agreement to be signed with Adani?

Even as BJP spokespersons have been vociferously supporting Adani’s cause, why is the Modi government not asking its agencies like the CBI, the Enforcement Directorate, and the Income Tax Department, which it has otherwise used with alacrity, to investigate former Chief Ministers like Jagan Reddy (who is no longer aligned with the BJP), Bhupesh Baghel of the Congress, Naveen Patnaik of the Biju Janata Dal, serving Chief Minister M.K. Stalin of the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam? It would perhaps be too much to expect the Lieutenant Governor of Jammu and Kashmir, Manoj Sinha of the BJP, to be probed.

Be that as it may, the person who is in a big quandary at present is N. Chandrababu Naidu, The Chief Minister of Andhra Pradesh, who, when he was in the opposition, had railed and ranted against Jagan Reddy’s government for “favouring” Adani. Naidu’s supporters even filed a public interest litigation (PIL) petition in this regard in the Andhra Pradesh High Court. Today, Naidu’s confidantes are waffling. One of them (Payyavula Keshav, Finance Minister of Andhra Pradesh) first said the State government’s agreement with Adani could be scrapped and then quickly backtracked saying “legal” options would be looked into.

The question being asked repeatedly is why these charges were filed in the US. Here is the reason: Adani Group companies, including Adani Green Energy, have raised funds by floating financial instruments—some of these have names that might sound exotic to lay persons, such as “green bonds” and “senior secured notes”—and these were subscribed to by investors from different countries, including the US and India. Among the flotations was one in August-September 2021 worth $750 million, of which $175 million was reserved for Americans. Another issue of bonds worth $409 million by entities in the Adani Group took place more recently in March 2024.

The law in the US, particularly the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA) of 1977, states that a bribe or an offer to bribe may have been paid/made in any country but would be considered a cognisable offence under American law if any citizen or entity of the US is affected. The allegation in this case is that Adani deliberately concealed from US investors that he and his associates were being investigated by American government agencies for bribing Indian officials for undue business advantages.

In other words, “price sensitive” information was not disclosed by the issuers of the financial instruments—this is, incidentally, an offence in this country as well under the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) (Listing Obligations & Disclosure Requirements) Regulations of 2015, subsequently amended in 2023. Besides, a bribe is a bribe, in the US, in India, or elsewhere. But that is another story.

India’s green energy landscape

The investigations in the US also did not find a place in the annual report of Adani Green Energy, even as the group claimed that it had “zero tolerance” for bribery and corruption and followed the “highest standards” of corporate governance.

Two senior lawyers, Mukul Rohatgi, former Attorney General of India who has represented Adani before, and Mahesh Jethmalani, Rajya Sabha MP affiliated to the BJP, both held press conferences on November 27 expressing their “personal views” that the allegations were “flimsy”, “baseless”, “malicious”, and “false”. Earlier that day, Adani Green Energy had issued its first public statement to the NSE denying media reports that it had been charged under the FCPA, even as it acknowledged that the DoJ and the SEC had charged it on three counts of conspiracy, fraud in transactions of securities, and “wire fraud” or transmitting false information through electronic means within and from the US.

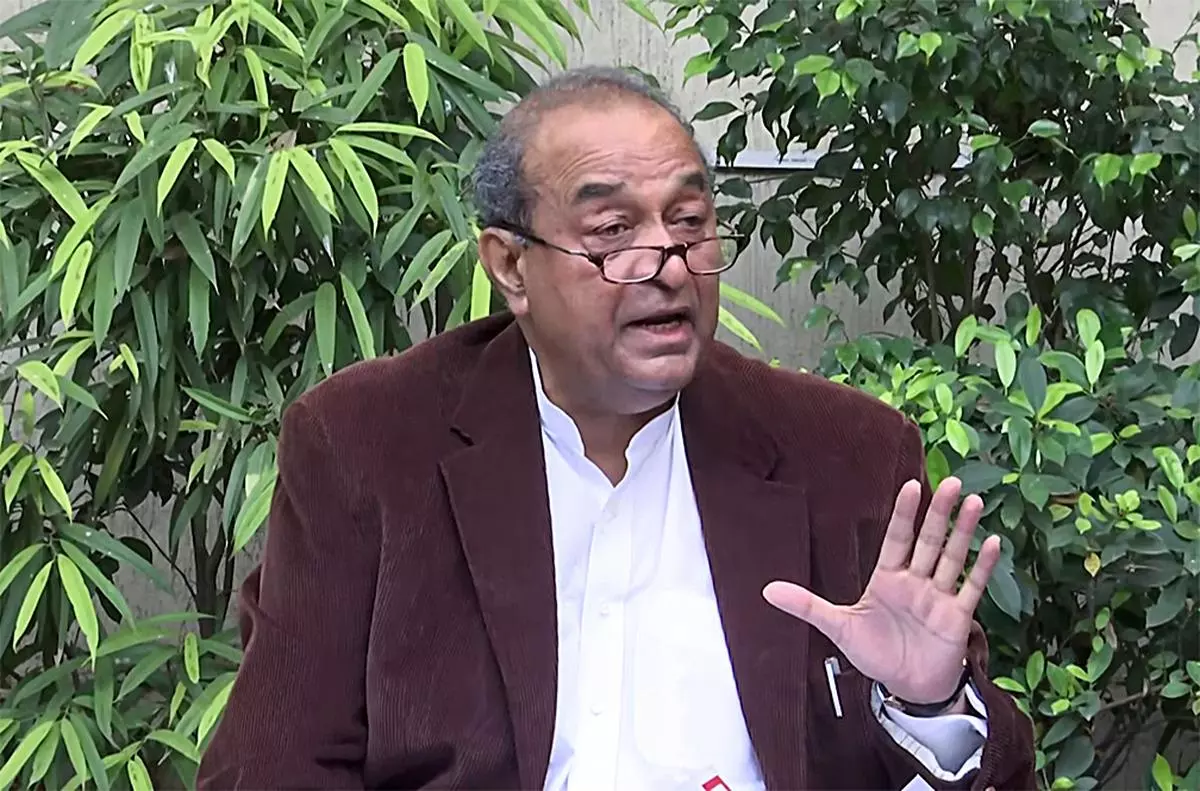

Former Attorney General and Senior Counsel Mukul Rohatgi speaks to the media on the allegations against the Adani Group in a US court, in New Delhi on November 27, 2024.

| Photo Credit:

ANI

The company’s share prices rose after this statement. It should be borne in mind that share prices in India rise and fall depending on various factors, including the purchase and sale decisions of foreign investors as well as large institutional investors such as Life Insurance Corporation and State Bank of India. The company’s stock price has collapsed by 83 per cent from its peak in January 2023, before the first Hindenburg Research report came out. Meanwhile, Adani called off a planned new offering of bonds worth $600 million. TotalEnergies of France, which holds a 37.4 per cent stake in Adani Total Gas, which supplies across the country, said it would not make fresh investments in the company. It also holds 19.7 per cent shares in Adani Green Energy.

Representatives of international banks and financial institutions have made several off-the-record statements. International publications have argued that the allegations against Adani would have a negative impact on India’s plans for increasing supplies of renewable energy. The Economist wrote that the indictment in the US “casts doubts on India’s business environment that could deter foreign investors and hinder other Indian companies’ fund-raising plans abroad”. Indian commentators like Sushant Singh, writing in The Caravan, argued that the “Adani saga will leave India strategically vulnerable on the global stage”.

GQG Partners, based in Australia and headed by financier Rajiv Jain, which bailed out Adani when shares of group companies collapsed after the first Hindenburg Research report, sought to play down the indictment and distance individuals from the corporate entity. Others pointed out that solar energy was only a small part of the Adani Group’s total business. Critics found these arguments disingenuous. Incidentally, GQG has stayed away from investing in Adani Total Gas.

In India, the Telangana government headed by A. Revanth Reddy has rejected a Rs.100 crore grant from Adani for a proposed educational institution. The leader of the Opposition, Rahul Gandhi, has called for Adani’s arrest, wondering why Chief Ministers Hemant Soren and Arvind Kejriwal could be arrested promptly but not Gautam Adani. The first week of the winter session of Parliament has been washed out. The INDIA bloc, however, is far from united. Trinamool Congress Member of Parliament, Derek O’Brien, was the first to argue that Parliament should not be held hostage to a single issue, namely, Adani.

Besides Gautam Adani, his nephew Sagar, Jaain, and four others indicted are, or were, associated with a Canadian pension fund CDPG, an acronym for Caisse de dépôt et placement du Québec, which has invested in Azure Power and whose officials allegedly co-conspired with Adani to bribe Indians. The officials are Cyril Cabanes of Australian-French origin based in Singapore and three persons who appear to be of Indian origin: Saurabh Agarwal, Rupesh Agarwal, and Deepak Malhotra. Arijit Barman of The Economic Times has reported that two persons associated with Azure, Alan Rosling of the UK and Murali Subramanian—who had both earlier worked in India—were the likely whistleblowers who informed the American agencies who probed the allegations of graft.

The same publication has also pointed out that not a single unit (kilowatt hour) of electricity has been supplied so far by Adani to SECI for Andhra Pradesh. Transmission facilities are not yet ready and relatively small quantities of electricity generated by Adani have been sold through power exchanges at a price 40 per cent higher than the price agreed upon with the State’s discoms.

Will Trump come to Adani’s rescue?

What happens now? Will the same Gautam Adani who threatened to sue Nathan Anderson of Hindenburg Research for defamation but has not done so for nearly two years have to now appear before the grand jury in the Eastern District of New York? Or will his lawyers appear for him? Will the situation change after Donald Trump takes office on 20 January and his nominees begin to head the DoJ, SEC, and FBI?

Trump has said several times that he is opposed to the “horrible” FCPA because it works against American business interests. But will he be able to dilute the law? Or repeal it altogether? Gautam Adani welcomed Trump’s re-election with fulsome compliments and publicly promised that his group would invest $10 billion (currently equivalent to Rs.84,000 crore) in America’s energy facilities and infrastructure, thereby creating 15,000 new jobs in that country. Did he have an inkling of what was to hit him weeks later?

The Indian government reacted to the Adani indictment for the first time on November 29. Randhir Jaiswal, spokesperson of the Ministry of External Affairs, said: “This is a legal matter involving private firms and individuals and the US Department of Justice. There are established procedures and legal avenues in such cases that we believe would be followed. The government of India was not informed in advance of the issue. We haven’t had any conversation also about this matter with the US government… Any request by a foreign government for the service of a summons/arrest warrant is part of mutual legal assistance. Such requests are examined on merits. We have not received any request on this case from the US side. This is a matter that pertains to private entities and Government of India, is not legally a part of it in any manner, at this point in time.”

Also Read | SEBI’s great surrender

India and the US have extradition treaties in place, but will Adani be extradited? Can cases be instituted against him in India to prevent him from leaving India? It is reported that SEBI has filed a show-cause notice against an Adani Group entity after completing investigations on alleged violation of rules relating to “ultimate beneficial owners” of companies and exceeding the limits of shares that can be held by a “promoter group”.

SEBI Chairperson Madhabi Puri Buch’s recent track record and the charges of conflict of interest levelled against her do not inspire confidence in the market regulator’s ability to take punitive action against the Adani Group. Nor does it seem likely that, based on the same set of allegations levelled in the US, law enforcement agencies in our country will act against him using laws such as the Prevention of Corruption Act of 1988, the Prevention of Money Laundering Act of 2002, or the Competition Act of 2002.

The Leaflet has quoted legal experts from the chambers of litigation, including Anurag Katarki, that the new Trump administration can theoretically defer prosecution or enter a plea bargain to absolve Adani of certain charges on the payment of fines.

On a personal note, as my wife and I entered Gujarat on a train early on the morning of November 21, my wife called our daughter to tell her about the arrest warrant against Gautam Adani. The line was unclear, and our daughter thought another arrest warrant had been issued against me, as it had been in January 2021. We told her the warrant was not against me, but the tycoon. When we relate this story to people, they smile.

Paranjoy Guha Thakurta is an independent journalist, author, publisher, educator and maker of documentary films and music videos. He was the lead author of a book titled “Gas Wars: Crony Capitalism and the Ambanis” in 2014.