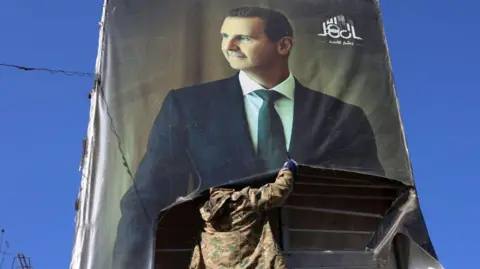

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe speed of the collapse of the Assad regime in Syria is giving us a real-time insight into the dilemmas of foreign policy.

The solid becoming fluid in the blink of an eye, and a whole array of awkward questions being posed.

A dictator flees, his regime collapses and Foreign Secretary David Lammy addresses the Commons, telling MPs that Assad is a “monster,” a “butcher” a “drug dealer” and a “rat”.

But things are moving quickly.

Asylum applications suspended

When asked whether the UK would be suspending asylum applications from Syria, Lammy indicated that he didn’t know.

He didn’t know that his cabinet colleague, Home Secretary Yvette Cooper, was saying, at pretty much exactly that moment, that they were being suspended.

In the year to September, the fifth largest number of asylum claims by nationality came from Syrians and nearly every claim – 99% – were granted.

But the government is now pausing applications, alongside France, Germany and others.

Why?

The main reason is that the vast majority of people applying for asylum from Syria were doing so, they said, because they were fleeing the Assad regime.

That regime has now gone and therefore so has, on the face of it, the central case being made in most applications.

The other reason, described as much less significant in numerical terms but still a potential cause for concern on security grounds, is Syrians associated with the failed regime themselves now trying to claim asylum.

Figures in government are now also contemplating the prospect that some Syrians in the UK may now want to return to their home country.

What comes next in Syria?

And what about what – and who – comes next in Syria?

There has been plenty of talk in the last few days about Hayat Tahrir-al Sham, or HTS.

The British government labels them a proscribed terrorist organisation.

The United States and the European Union attach their own labels which amount to broadly the same thing.

Being proscribed means it is a criminal offence for people to promote, support or be a member of the organisation.

And in practical terms it means the government can’t have a conventional diplomatic relationship with it.

That is one thing, when it is an organisation it doesn’t want to have anything to do with, quite another if it ends up being the recognised government of a country.

So how soon could HTS be de-proscribed?

Cabinet Office Minister Pat McFadden, one of the most senior figures in the government, told the BBC there could be a “relatively swift decision” on whether to talk to HTS.

But fast forward a few hours and both the foreign secretary and the prime minister were emphasising a much slower pace, saying – in line with the message from the White House – that HTS would be judged on its actions, with the implication this could take time and would not be rushed.

Lammy said it was right to be “cautious”.

Sir Keir Starmer said “no decision is pending at all.”

So much has changed so quickly in Syria, with multiple implications and posing difficult decisions – and there will be plenty more to come.