Plagiarism is a big area of concern that is rearing its ugly head worldwide. The act of representing someone else’s ideas, thoughts, language, or expression as original work, plagiarism not only discourages creativity, but also steals from the actual creators. In a world with artificial intelligence (AI) that we live in, more checks and balances are currently being sought after as it has become easier than ever to plagiarise.

Plagiarism, however, hasn’t been a concern just now and has probably been around for as long as ideas and expressions have been exchanged. Charges of plagiarism, when proven, can tarnish a person’s reputation, dealing them a blow from which they can probably never stand up again. On some occasions, just the charges are enough to sideline someone, even if they aren’t proven beyond doubt. German astronomer Simon Marius was at the receiving end of one such episode over 400 years ago.

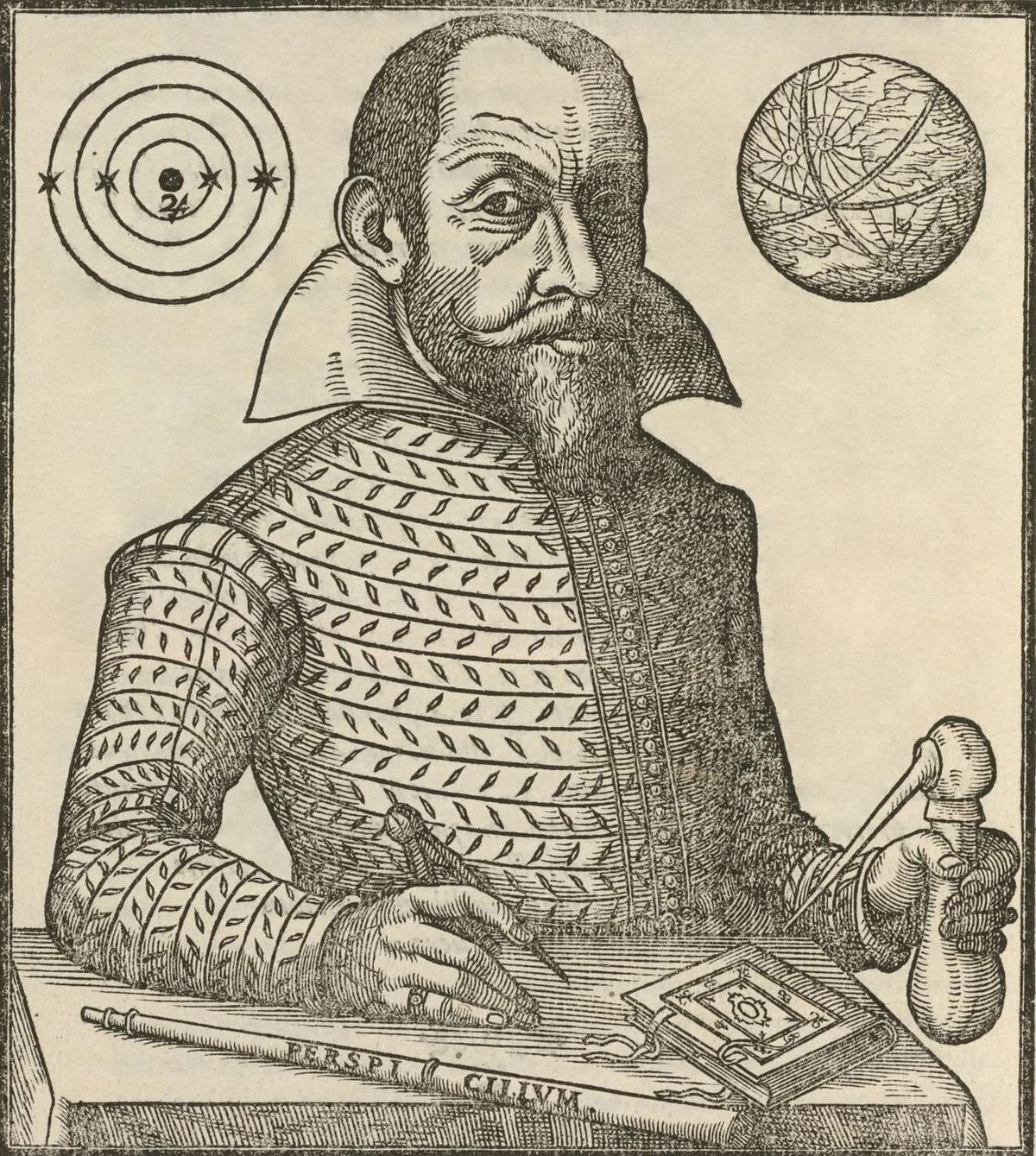

This portrait of Marius appeared as a frontispiece (illustration facing the title page of a book) to the Mundus Iovialis. In addition to containing the first printed image of a telescope, it also shows Jupiter’s moons in orbit around the planet – something that Galileo didn’t include in his book.

| Photo Credit:

WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

An astronomer, mathematician, physician, and calendar maker, Simon Mayr was born in Gunzenhausen in 1573. Marius was his Latinised name for the international scientific community, as was the fashion of the times.

Starts with a song

The story goes that when George Frederick, Margrave of Brandenburg-Ansbach, heard young Marius singing, the regent took a liking to him. As a result of this, Marius was enrolled in the Fürstenschule at Heilsbronn, where he studied until 1601. Even though his plans to study at Königsberg didn’t fruition, he managed to meet celebrated Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe at Prague in 1601.

His career also took shape through the time he spent south of the Alps, as he studied medicine in Padua until 1605 before becoming a medical practitioner. It was probably during his time at Padua that his path first crossed with Galileo Galilei and the two men might have met. From 1606, until his death in 1624, Marius served as the court mathematician at Ansbach in Germany.

Belgian spyglass

Having settled in Ansbach in 1606, Marius’ first attempts to construct a telescope weren’t successful owing to the poor quality of the glass. By 1609, however, he possessed a Belgian spyglass, thanks to his friend and military man Johannes Philipp Fuchs von Bimbach.

As someone who had already observed the comet of 1596 and established the position of a supernova in 1604 with his unaided eye, Marius didn’t need telling twice to employ the telescope for astronomy. He took a look at Jupiter using this on December 29, 1609 according to the Julian calendar in use in his region (January 8, 1610 according to the Gregorian calendar) and saw “… four tiny stars, sometimes behind, sometimes in front of Jupiter, aligned in a straight line with the planet.” If this were true, Marius had, in fact, independently discovered the four major moons of Jupiter.

Flame of a candle

Nearly three years later, on December 15, 1612, Marius became the first person to use a telescope to observe the Andromeda Galaxy. In the interim years, he had observed the phases of Venus and also sun spots.

He published his scientific results in his 1614 Mundus Iovialis (The World of Jupiter). In this, he described his sighting of the Andromeda Galaxy as “like a candle seen at night through a horn” – the horn being a reference to the horn lanterns that were in common usage back then. Additionally, the book also mentioned his sightings of the Jovian satellites, including the dates.

Galileo’s outrage

Galileo, who had observed Jupiter’s four major moons (now also called as the Galilean moons) on January 7, 1610 (Gregorian calendar), had already published Sidereus Nuncius (The Sidereal Messenger) in Venice in 1610 and was the first to announce the discovery. He was incensed by Marius’ claims four years later of observing these moons just a day after him and saw it as an attempt to usurp his priority. He retaliated in his 1623 book Il Saggiatore (The Assayer), accusing Marius of plagiarism.

More than four centuries on, debate on the validity of Marius’ claims still persists. The shadow of plagiarism looms so large over Marius’ works that credit isn’t given even where it is due. This not only includes his observation of the Andromeda Galaxy, but also the accuracy of his tables of the moons of Jupiter.

While it is nigh impossible for us to determine if Marius does deserve credit for independently discovering the four major satellites of Jupiter, there’s no doubt that he was the one who gave them the names that are now in use. Galileo had called them the Medicean moons in honour of his patrons (the Medici family), but Marius mulled on the suggestions provided to him by renowned German astronomer and mathematician Johannes Kepler and decided on calling them Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto – Jupiter’s companions from Greek mythology. While astronomers preferred calling them as just I, II, III, and IV – just as Galileo had referred to them numerically – for over 300 years, the names that Marius suggested finally won over when these moons got more character thanks to advances in astronomy.

Was Marius the first to observe the Andromeda Galaxy?

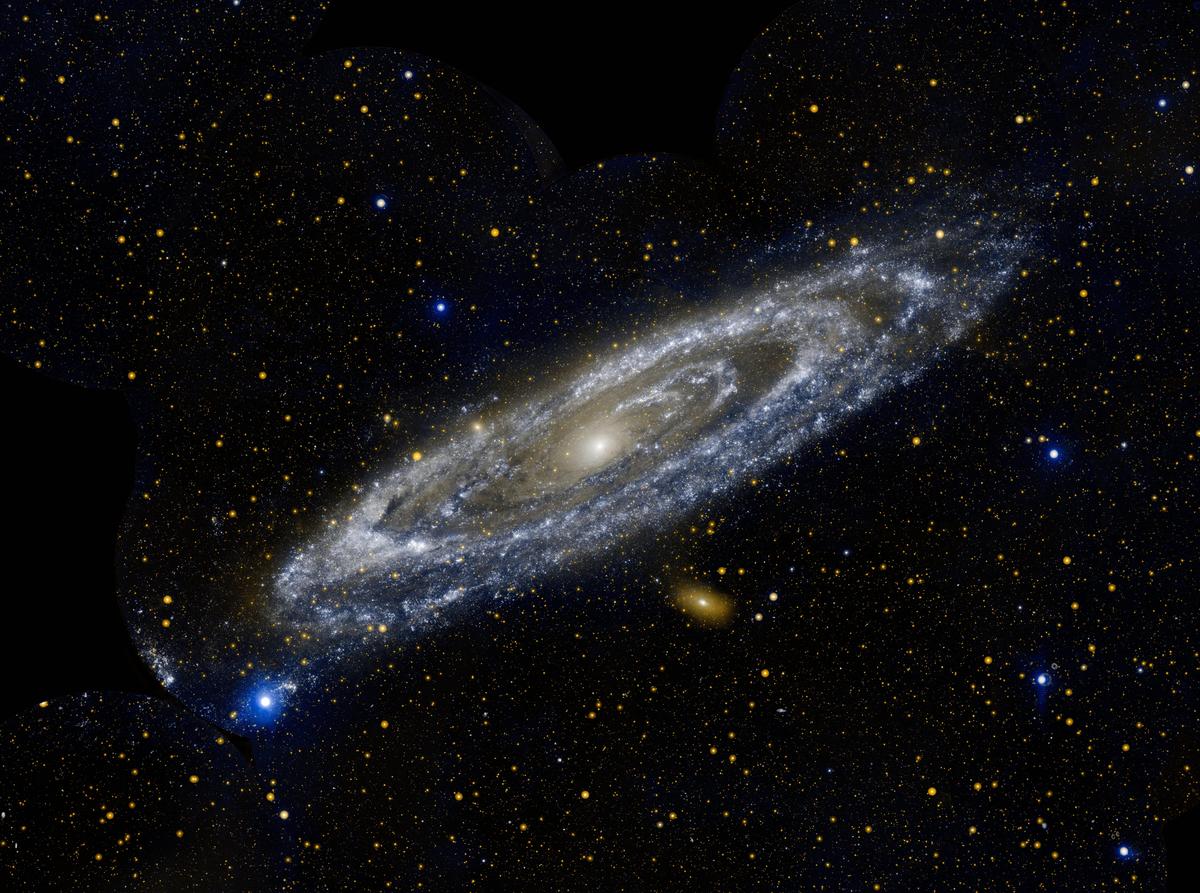

This image obtained from NASA and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory shows the Andromeda Galaxy.

| Photo Credit:

AFP PHOTO / NASA/Jet Propulsion Laboratory

Simon Marius was the first to employ a telescope to observe the Andromeda Galaxy. But was he the first person ever to observe it? The answer is no.

A spiral galaxy that is similar in size and structure to our own Milky Way, Andromeda is only slightly larger and is the nearest major galaxy to the Milky Way.

Despite its size, the Andromeda is only about six times larger than the moon in the sky. This is because the moon is much closer to the Earth, while the Andromeda Galaxy is about 2.5 million light-years away.

The Andromeda Galaxy, in fact, is the one thing located outside our galaxy that is visible to the unaided eye. It can be seen from dark locations, but it can’t be seen clearly as it is too dim.

This, however, means that the Andromeda Galaxy could be observed much earlier. The earliest such recorded observation was by Persian astronomer Abd al-Rahman al-Sufi, who caught a glimpse of the galaxy (without a telescope of course) and recorded it in his Book of Fixed Stars in the year 964.

Al-Sufi’s priority, however, was reestablished only in 1667 when French astronomer and mathematician Ismael Boulliau published the al-Sufi drawing of Andromeda in his pamphlet about the galaxy.

This makes it clear that Marius’ discovery was on his own. His description of a fuzzy patch, a nebula, in Andromeda in the Mundus Iovialis, however, did not have an image.

The picture of Marius’ monument in Ansbach that has been used as our cover image was obtained with permission from the website Statues – Hither & Thither.

Published – December 15, 2024 12:41 am IST