John-Jonne Smith enjoyed a flourishing head of hair for much of his life. The young millennial rocked different hairstyles and loved switching it up: a curly Afro one week, two-strand twists the next, micro plaited braids and a range of cornrow designs.

But when Smith was 18, during his senior year of high school, his hair started thinning.

“That’s when I first noticed it, but I was in denial,” he says. “Everybody knew me for having hair and different designs. I even taught myself how to braid my own hair when I was a kid, and sometimes I’d help my homegirls and cousins flat iron and braid their hair during class.”

By 21, a harsh reality had become unavoidable: Smith was in the beginning stages of permanent hair loss caused by androgenetic alopecia, which affects an estimated 50 million men in the U.S. by age 50. Doctors told Smith the sudden hair loss was hereditary, which didn’t provide much comfort considering the men in his family had full heads of hair well into old age.

Still, there’s a growing silver lining: In today’s digital age, the once hush-hush experience of a man privately processing going bald, or secretly seeking out cosmetic alterations — from temporary hair units (a.k.a. male hair pieces, or “man units”) to hair transplant procedures in cosmetic surgery hubs like Turkey — has entered the mainstream consciousness. Video mashups of barbers transforming their male clients with man units have racked up millions of views and sparked spirited commentary online, where men share heartfelt testimonies on how losing their hair rattled their confidence.

After his diagnosis, Smith frantically added hair powders and Rogaine to his daily morning and evening routines, attempting to hide his balding from the eyes of others.

Life is full of curveballs, he says, remembering a fateful day in L.A. he spent substitute-teaching a class of eighth graders. While the class was outside during a break, unexpected rain poured down. As Smith and his class rushed back into the classroom, patches of the hair he had started the day with were washed away, while other sections dripped down his face.

Actor and filmmaker Smith, who lives with male pattern baldness, has turned his hair journey into creative inspiration.

(Marcus Ubungen / Los Angeles Times)

“The kids were pointing and screaming like, ‘Oh my God, mister, what happened to your hair?!’ I checked my phone and looked at the camera and gasped,” he says. “I was like, ‘Who did this? Who did this to me?’ trying to play it off. Thank God I wore a hoodie that day and just put the hood on top of my head.”

There was no mercy from the middle schoolers: The roasting was plentiful. Thankfully Smith didn’t have to return to substitute teach at the school the next day.

“Using the Rogaine and the hair powders — that was my grieving for five years,” says Smith, who describes the period of time as fighting a losing battle that ultimately led to self-acceptance.

“Being bald is OK, but going bald is horrible,” says Stuart Heritage, journalist and author of “Bald: How I Slowly Learned to Not Hate Having No Hair.” “It sounds like such an overblown thing to say, but it’s almost like a small bereavement when your hair goes. There’s a fear of the unknown, and you do go through the five stages of grief.”

Becoming a member of the global no-hair club isn’t all gloom and identity crises though, says Heritage. Your personal maintenance routine becomes much quicker. Plus, not having hair can be a refreshing point of connection between men who’ve experienced hair loss.

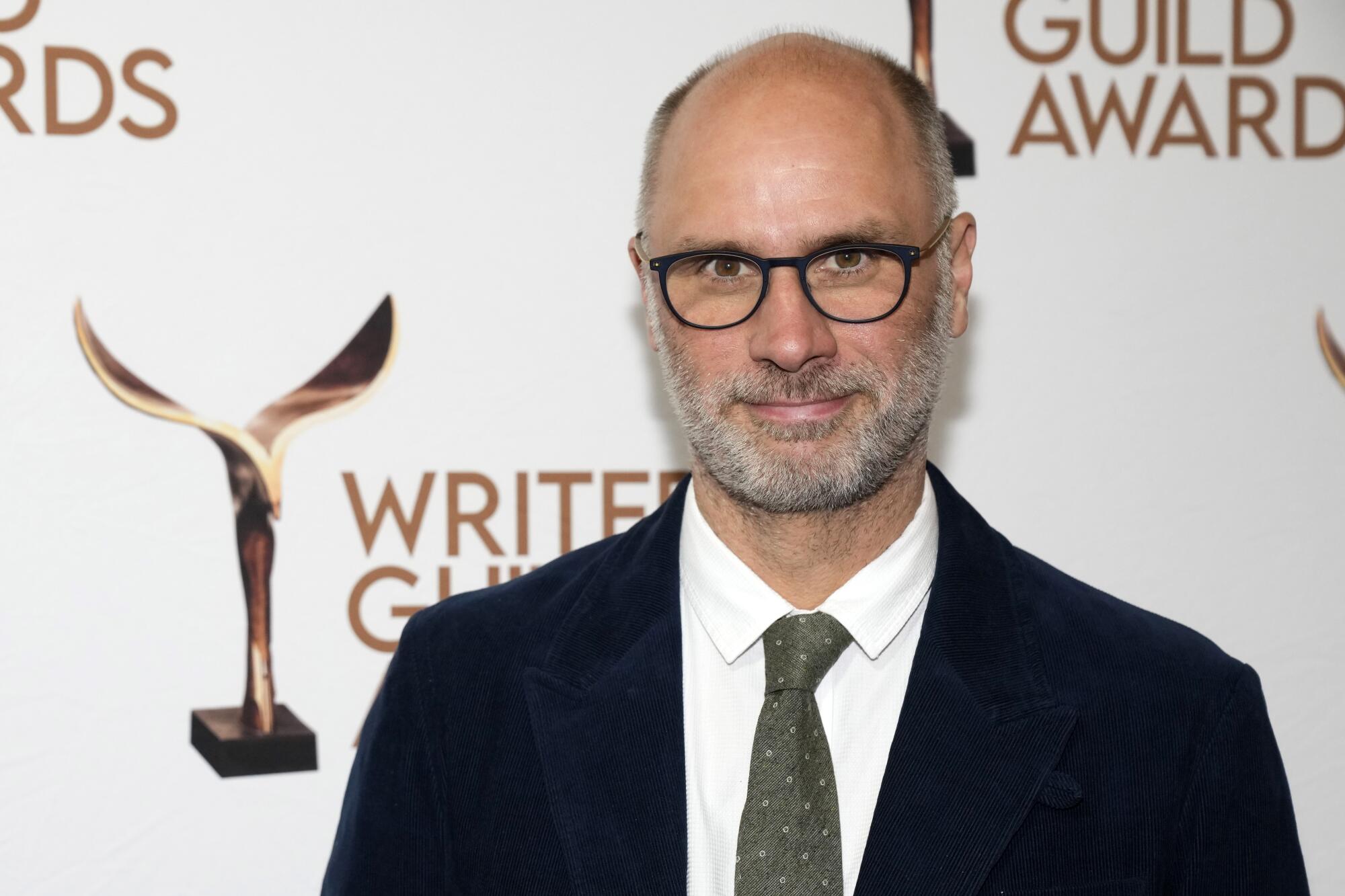

Jesse Armstrong, creator of HBO’s “Succession,” has a story about noticing he was going bald. So does Larry David.

(Charles Sykes / Invision / Associated Press)

“If you can talk to a bald person about how they went bald, it’s always fascinating,” Heritage says. For example, when Heritage interviewed Jesse Armstrong, creator of HBO’s hit series “Succession,” about the Season 3 finale, the topic came up.

“I hope he doesn’t mind me saying this,” says Heritage. “He was at a university, and one of his professors sort of came up behind him and slapped him on his bald spot. And that was the first time he noticed that he was going bald.”

Then there’s Larry David, whom Heritage interviewed for his book. “He was playing softball, l think, and he was wearing a cap,” Heritage says. “He took it off to scratch his head and realized that he was just running his hands through flesh.

“The stories are in there; they just take a bit of prodding to come out,” he says. “Bald men would love to be able to talk about it, but I think they feel quite restrained by the boundaries of traditional masculinity.”

For Smith, a revelatory moment for both his look and his art came during the COVID-19 pandemic, as he was figuring out how to grow a solid body of acting work. “I was trying to find out what my niche was,” he says, recalling the questions that helped steer him in the right direction: What is my story? What am I embarrassed about? What am I trying to hide from the world?

Inspiration struck after Smith watched the film “A Boy, a Girl, a Dream,” in which a character struggles to release the work he created into the world. Reading the screenwriting book “Save the Cat,” which walks storytellers through the process of how to structure a screenplay, was also a major source of motivation for Smith to write, create and star in the short film “Bald” in 2020.

The positive reception the project was met with led to Smith creating two seasons (14 episodes) of “Bald,” the web series, which aired on Facebook Watch in 2021 and 2022. Today, Smith also hosts a comedy variety show, “Unserious,” airing on all major social platforms, and is shopping around a pilot and working on a feature-length version of the “Bald” short.

Smith has a hair kit applied to his scalp by Rhodes. “Previously, many barbers didn’t understand or they weren’t willing to understand,” say Rhodes, who opened a barbershop inside his home.

(Carlin Stiehl / For The Times)

These semi-autobiographical works offer a glimpse into Smith’s experience navigating identity, dating in Los Angeles as a bisexual man, hair loss and the discreet use of hair powders and man units, which the 20-something chronicles on his Instagram and TikTok accounts as well. A recent Instagram post lists the benefits of rocking a bald head; other videos show an array of hair transformations.

“It was breathtaking to know people resonated with what I put out there,” Smith says.

Artist and L.A.-based barber Jamal Rhodes, a.k.a. the Dope Barber, is Smith’s go-to person for haircuts and man units. He’s seen the growing acceptance of man-unit applications firsthand. “Previously, many barbers didn’t understand or they weren’t willing to understand,” says Rhodes, who began offering hair-unit services in 2020, shortly after relocating to Los Angeles from Houston.

The meticulous application process takes about two hours, and entails cutting the client’s remaining hair to prep the bald areas for the hair strips. Each hair strip is matched to the client’s unique hair texture, then the barber applies the hair strips to the client’s bald areas, blending them in with the existing hair.

“[Other barbers] were so quick to criticize or to make fun of what I was actually doing,” he says. Also, the men who came in didn’t feel comfortable asking for what they wanted out in the open of the barbershop. “I really wanted to give them that space to just be who they are when it comes to their hair,” says Rhodes, who now runs his barbershop out of his home.

For some, man units are a way to hold on to a sense of familiarity and confidence around their appearance. For a growing number of others, hair pieces are an option to reach for when the mood to remix their look strikes.

Jamal Rhodes preps Smith’s head for hair strips. (Carlin Stiehl / For The Times)

Rhodes applies man units to Smith’s scalp. (Carlin Stiehl / For The Times)

It’s fun to channel personal self-expression through hair, says Smith, who adds that rotating hair colors feels like a mix of playing dress-up and sporting a visible mood ring atop his head.

So far, he’s donned man units in black, dark brown and ginger for Paris Fashion Week, and, after a difficult friendship breakup, he was a two-toned platinum blond, which he calls his “breakup hair” and his “Kim [Kardashian] after Pete Davidson hair.”

Smith plans to try out man units in mahogany, blue and green in the near future. “If you see something on top of my head, it’s glued down and it looks very good thanks to Jamal,” he says. “We really work together to see what new thing we can try next and [fun ways to experiment] with color.”

Smith’s adventurous fashion taste also includes a wide array of hats — vibrant fitted caps, eye-catching cowboy hats, berets and more. “It becomes a conversation starter. Velour, satin, etc. — I love rocking a Black-owned business,” he says. “I’ll wear a colorful hat as a pop of color to a neutral fit if I’m growing my hair out for a man unit for the two-week duration — or, as some of us like to call it, the ‘ruff period of hair growth.’ Otherwise I’m bald.”

As more stories about men coping with hair loss enter the mainstream, Smith hopes people remember that whoever you are is OK. “You’re still gonna be able to live life and make the money and do the projects and live out your dreams, whatever that looks like for you. This is what my journey looks like,” he says. “I didn’t want to keep it from people, because I know I’m not the only one who’s going through this.”

1

2

3

1. The process, which takes about two hours, involves prepping the scalp, matching hair strips to the client’s hair texture, applying strips to the bald areas and blending them with the hair. (Carlin Stiehl / For The Times)

“It’s fun to channel personal self-expression through hair,” says Smith.

(Carlin Stiehl / For The Times)