Shyam Benegal, who heralded a new era in Hindi cinema with the ‘parallel movement’ in the 1970s and 1980s with classics such as Ankur, Mandi and Manthan, died on Monday, December 23, after battling chronic kidney disease. He was 90.

The filmmaker, a star in the pantheon of Indian cinema’s great auteurs, died at Mumbai’s Wockhardt Hospital, where he was admitted in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU). “He passed away at 6.38 pm at Wockhardt Hospital Mumbai Central. He had been suffering from chronic kidney disease for several years, but it had gotten very bad. That’s the reason for his death,” his daughter Pia Benegal told media. He is survived by his daughter and wife, Nira Benegal.

Just nine days ago, on his 90th birthday, actors who had worked with him through the decades gathered to wish him on the landmark day, almost as a last sayonara to the filmmaker who had given them perhaps the best roles of their careers. Among those who had gathered were Shabana Azmi, who made her debut with the powerful Ankur in 1973; Naseeruddin Shah, Rajit Kapoor, Kulbhushan Kharbanda, Divya Dutta, and Kunal Kapoor. That photograph of a smiling Benegal with his actors down the ages is his last in public.

Many worlds, many forms

In his prolific, almost seven-decade career, Benegal straddled diverse worlds, diverse mediums, and diverse issues, right from rural distress and feminist concerns to sharp satires and biopics. His oeuvre encompassed documentaries, films, and epic television shows, including Bharat Ek Khoj, an adaptation of Jawaharlal Nehru’s Discovery of India, and Samvidhaan, a 10-part show on the making of the Constitution.

And he wasn’t calling it quits anytime soon. “I’m working on two to three projects; they are all different from one another. It’s difficult to say which one I will make. They are all for the big screen,” Benegal said on the occasion of his 90th birthday. He also spoke of his frequent visits to the hospital and that he was on dialysis. “We all grow old. I don’t do anything great (on my birthday). It may be a special day, but I don’t celebrate it specifically. I cut a cake at the office with my team.” His films include Bhumika, Junoon, Suraj Ka Satvaan Ghoda, Mammo, Sardari Begum and Zubeidaa, most counted as classics in Hindi cinema.

Also Read | Kumar Shahani (1940-2024): A polymath’s relentless search for a unique cinematic idiom

His biopics include The Making of the Mahatma and Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose: The Forgotten Hero. The director’s most recent work was the 2023 biographical Mujib: The Making of a Nation. He was also keen to bring to life the story of Noor Inayat Khan, the secret WW II agent. That dream will sadly remain unfulfilled.

Benegal’s Manthan on Varghese Kurien’s milk cooperative movement in Anand, Gujarat, starring Smita Patil, Girish Karnad, and Naseeruddin Shah, was restored and screened at the Cannes Classics segment in the French Riviera town in May this year.

A poster of Ankur, directed by Shyam Benegal.

Tributes

Tributes to Shyam Babu, as he was known to friends and colleagues, who rewrote the rules of Indian movies, poured in. President Droupadi Murmu condoled the demise of Benegal and said his passing away marks the end of a glorious chapter of Indian cinema and television. Murmu said Benegal started a new kind of cinema and crafted several classics. “A veritable institution, he groomed many actors and artists. His extraordinary contribution was recognised in the form of numerous awards, including the Dadasaheb Phalke Award and Padma Bhushan. My condolences to the members of his family and his countless admirers,” the President said in a post on X.

The Congress condoled the passing of Benegal, with party chief Mallikarjun Kharge saying his tremendous contributions to the art form, marked by thought-provoking storytelling and a profound commitment to social issues, left an indelible mark.

Filmmaker Shekhar Kapur said Benegal created ‘new wave’ cinema and will always be remembered as the man who changed the direction of Hindi cinema with films like Ankur and Manthan. “He created stars out of great actors like Shabana Azmi and Smita Patil. Farewell my friend and my guide,” he added.

“If there is one thing Shyam Benegal expressed best: it was the poetry of the ordinary face and ordinary lives,” director Sudhir Mishra said. “Much will be written about Shyam Benegal, but for me, not many talk about the fact that there was a lament in his films and a sadness about the fact we were not living in the best of all possible worlds,” he added.

Director Sandip Ray described the death of Benegal as a personal loss for the Ray family, recalling that the ace director had made a documentary on his father, the legendary Satyajit Ray, whom he affectionately called ‘Manikda.’ Sandip remembered how the two shared a warm, personal bond that deepened after the filmmaker made Ankur. He also recalled how renowned filmmaker made the documentary on Satyajit Ray, one of the most comprehensive works on his father’s life and career, and showed a keen interest in the restoration of Ray’s films. Sandip shared an anecdote where Benegal once remarked, “There is only one Ray.”

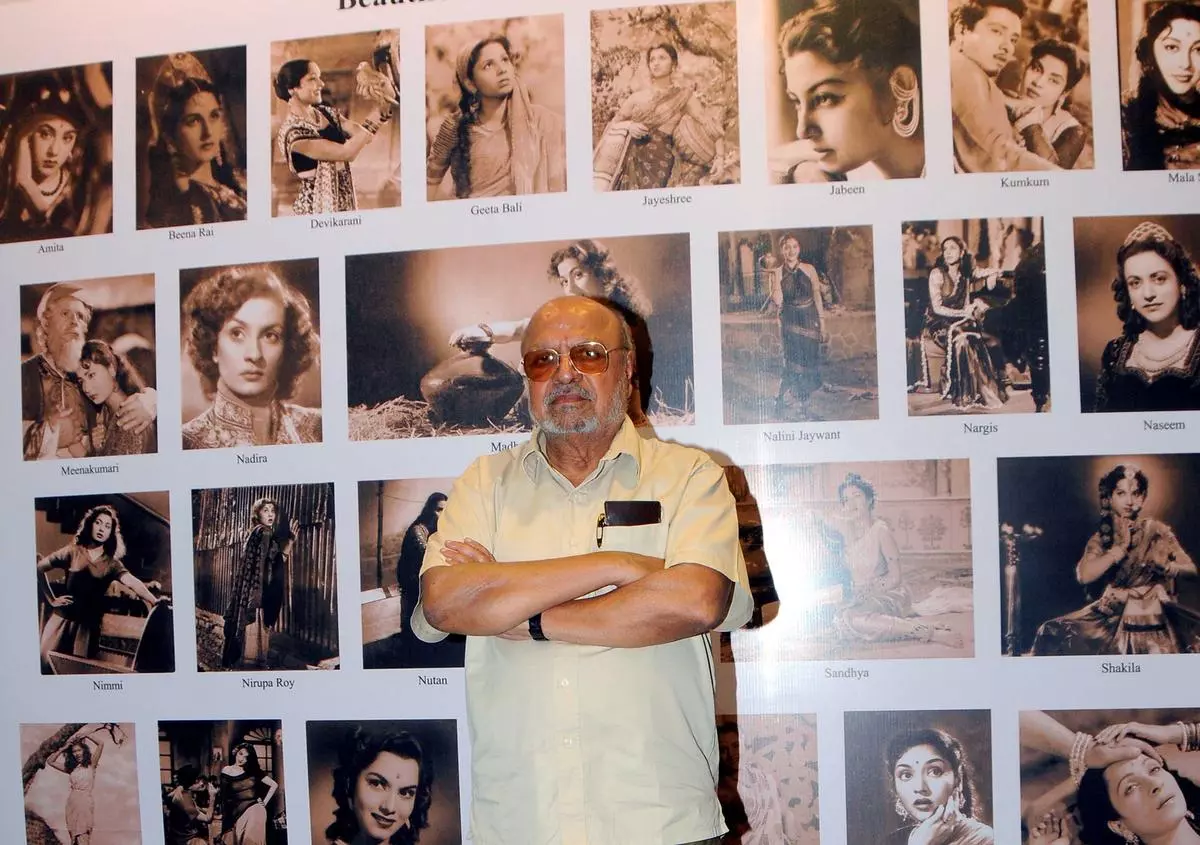

Shyam Benegal poses as he attends the screening of his documentary film The Master Shyam Benegal written by Khalid Mohamed and produced by Anjum Rizvi, at a function organised by The Asiatic Society of Mumbai and Mumbai Research Centre in Mumbai on March 20, 2014.

| Photo Credit:

FAP

Personal and political

Born in Tirumalagiri, now in Telangana, Benegal grew up with cinema around him. His father was a still photographer who also made short films. He was also a second cousin of film legend Guru Dutt. Benegal did his masters in economics from Hyderabad’s Osmania University. He planned to take up teaching but decided against it. The young Benegal soon moved to Mumbai looking for work and initially thought about assisting Guru Dutt but gave up on that as he had his own ideas.

Next, he took up a job as copywriter at an advertising agency. After a while, his agency shifted him to the film department sensing his inclination towards the medium where he began making ad films until becoming a full-time filmmaker. He then made documentaries for the Films Division of India before making his feature film debut with Ankur.

Benegal’s filmmaking was both deeply personal and inherently political. Telling stories of class and caste struggles, feminist concerns, rural distress and community dynamics. The gaze was incisive, the themes serious and the treatment sometimes sombre and other times satirical.

If Kalyug is a modern day retelling of the Mahabharata, Bhumika is a searing profile of a woman filmstar and her often exploitative relationships, Mandi deals with a brothel and its occupants who deftly navigate the men in their lives and Welcome to Sajjanpur about an aspiring novelist turned letter writer is an outright satire.

Also Read | Out of focus: Review of ‘ReFocus: The Films of Shyam Benegal’

Benegal disliked the term “middle cinema” used to bracket his films and preferred that his work be called “new or alternate cinema”. “I don’t remember who said this: ‘Every social act of yours is also a political act whether you like it or not’,” he told PTI in 2022. “One has to be as objective as possible and the second point is to be sympathetic. If you are not objective, you are already colouring the story with your subjectivity. Sympathy is necessary. When I say sympathy, I mean empathy so you can be one with the subject,” Benegal said.

His was the cinema of and by the erudite, attracting some of the most talented in the business. The late playwright Vijay Tendulkar wrote the screenplay Manthan and Nishant. The late music composer Vanraj Bhatia, cinematographer Govind Nihalani and the great theatre director Satyadev Dubey worked with him in multiple films. Girish Karnad wrote the screenplay for Bhumika and Ruskin Bond for Junoon.

Benegal was understated about his achievements. “There are people who have done wonderful things. There’s nothing unique in what one has done. You do what you think you want to do. That’s not unique. Climbing Mount Everest is unique,” he said.

With inputs from PTI