As tributes overflow for tabla maestro and composer Ustad Zakir Hussain, who passed away at 73, on December 15, contrarily, words seem to leave me. The only thing that occupies my mind is that an effervescent life was snatched away prematurely. How does one pay homage to this remarkable man, who wore his legacy and talent so lightly?

As I try to surmount this “how-to-say” conundrum, what emerges is a collage of memories: musical and personal.

I met Ustad in December 2006 at the Windsor Manor hotel in Bengaluru. We sat down for an interview at the café. A little while into the interview, Ustad appeared distracted. His eyes followed someone. A minute later, he asked me: “Isn’t that Dr Rajkumar’s son?” I turned around to look, and it was indeed the Kannada actor, Puneeth Rajkumar. The next minute he was up and took me along to the table where Puneeth was seated. “I am Zakir Hussain,” he introduced himself. I recall Puneeth, taken by surprise at the sudden darshan of the maestro, trying to say “of course, of course….” Ustad offered his condolences. “Your father was a great actor and his contribution to the Indian film industry is immense. Our family had great respect for him,” he continued referring to the thespian Dr Rajkumar who had passed away in April that year.

Groomed in the traditional repertoire of the Punjab gharana by his father, the legendary Ustad Allah Rakha, Hussain was phenomenally talented. He also got the right break with the right people: early in his life, he played with iconic musicians such as Pandit Ravi Shankar, Ustad Ali Akbar Khan, Pandit Shivkumar Sharma, and Pandit Hariprasad Chaurasia. They all came from different schools of music and with highly individualistic styles. This inspired Hussain to bring in several layers to the art of accompanying instrumentalists.

An attentive accompanist

In fact, he set a benchmark for tabla players of not only his generation but also of those who came after him. Hussain became a huge database of listening, knowing, and learning: he was extremely attentive as an accompanist, giving his all to the concert. The main function of the tabla artiste, he believed, was to “sangat karna” (to accompany) and all the other facets only followed. In an interview with the lyricist Javed Akhtar, Hussain rued that all attention of a tabla player today is on speed: “Tabla jis raftar mein chal raha he aaj, mein to soch bhi nahin sakta! [The way the tabla is being played today, I cannot even think at that speed!] But I don’t think they are really thinking about how they can be good accompanists.” Hussain, as most senior musicians say, despite his global status, was a mature accompanist and remained humble always.

It was perhaps 2010. Hussain visited Bengaluru for a fundraising concert with Ustad Sultan Khan. Media interviews were scheduled and one journalist present was from a new music magazine. The journalist had barely been introduced and the maestro took off. “Tell your editor I am boycotting your magazine. I saw the latest issue and it is clear that you have no respect for senior musicians. If this is your attitude, you should not even call yourself a music magazine.” The cover of the magazine had a young, pretty musician who was yet to make her mark, and the legendary sarangi player, Ustad Sultan Khan occupied a stamp-sized corner. Hussain was rightly enraged and made sure that the journalist left the room, while Ustad Sultan Khan sat quietly.

Also Read | Master of rhythm

Hussain settled down in the US in 1970; this gave him much freedom to experiment and collaborate with other forms of music. However, it did not change what he had learnt traditionally, and till the very end, he firmly retained his identity as an Indian classical musician. This was such a strong force within him that he did not even forfeit his Indian passport. He was a musician who could think and express himself with great clarity and honesty. He often said that eclectic concerts drew huge audiences but they were no measure for good music. On the contrary, “The impact Hindustani classical music has on me cannot be achieved by any of the other forms that I play,” he said.

Invariably, he was asked questions about fusion music, considering he was among the earliest who fraternised with music other than his own. Hussain had an elaborate, nuanced answer taking the complexities of the question into consideration. He said the advent of Hindustani music into India was through Amir Khusrau, who had training in the Prabhandh, Haveli, and Dhrupad forms of music. When he created the Khayal form, he added to this some elements from Qawwali music. “This is a kind of fusion, as you call it today. All Indian classical musicians are already sitting in a hybrid, mutated form. The dos and don’ts of this form were firmly in place,” he said, going back to the beginning.

“This category called fusion was a much later creation by music companies, because they needed categories to sell… That is when the organic need to have a conversation between two systems of music was lost. ”Ustad Zakir HussainTabla maestro and composer

Moving to the 20th century, he explained: “When Pandit Ravi Shankar and Yehudi Menuhin created music together it was called music, when Shakti came into existence it was called music… This category called fusion was a much later creation by music companies, because they needed categories to sell. And once the category was created there was a demand to produce more. That is when the organic need to have a conversation between two systems of music was lost. Fusion became confusion once it went on this road.”

Hussain, in a light hearted way, called gharana, daraana (to scare someone). “If someone asks me what my gharana is, I am not sure if I have an answer,” said the maestro at the “Sitar Gharanas of India” seminar at the National Centre for the Performing Arts, Mumbai, 2016. He explained: “I listen to recordings of my father Ustad Alla Rakha and his guru, and I find there are no similarities between them and me. I learnt from them, listened to them, practised under them and have absorbed, followed, emulated, and incorporated it into my music. Yet, when I play it bears no resemblance to what I learnt.”

Also Read | A legend is born

He reiterated that for a passionate student of music, “gharana” is never central to the process, it gives a direction to one’s thinking, but what he builds out of it is his own. “I am surprised that there are nine gharanas of sitar, and am even more surprised that there is no Ustad Vilayat Khan gharana and Pandit Nikhil Banerjee gharana, the brightest stars of sitar,” he observed. He recalled an incident when his father Ustad Alla Rakha’s friend proclaimed Zakir’s genius by saying how his art resembled his father’s. Allah Rakha had replied: “That’s a discredit. Zakir’s music should have his genius in it and not mine.” One could not miss the fact that for Hussain, an important aspect of tradition is indeed continuity where the core remains unaltered, it only comes in a new package.

I have another memory from 2016, when the Masters of Percussion, a musical ensemble, was put together by the inimitable Hussain. It was a confluence of rhythms that celebrated the diverse streams of percussion, both Indian and global, with six other stars of music: V. Selva Ganesh, Steve Smith, Niladri Kumar, Dilshad Khan, Vijay S. Chavan, and Deepak Bhatt.

A frenzy

Just a glimpse of Hussain would send the audience into a frenzy, and you can imagine what happened when he placed his fingers on the table; they could not stop applauding. The Ustad made repeated requests that evening, and kept saying to the audience to applaud “baad mein” (later), but there was no stopping this huge crowd that had crammed into every perceivable corner of the massive auditorium.

Hussain, an international phenomenon, who had collaborated with the world’s best musicians, was in essence rooted in the classical. Opening with the 16-beat rhythm cycle to Sarangi lehra, Ustad’s relentless study of his medium and the years of formidable hard work were there for all to see. He played traditional bol patterns, which included the top pharan (worked out from the sound of the canon), farmaishi pharan, and others. The rela that followed was stunning for its precision and consistent momentum.

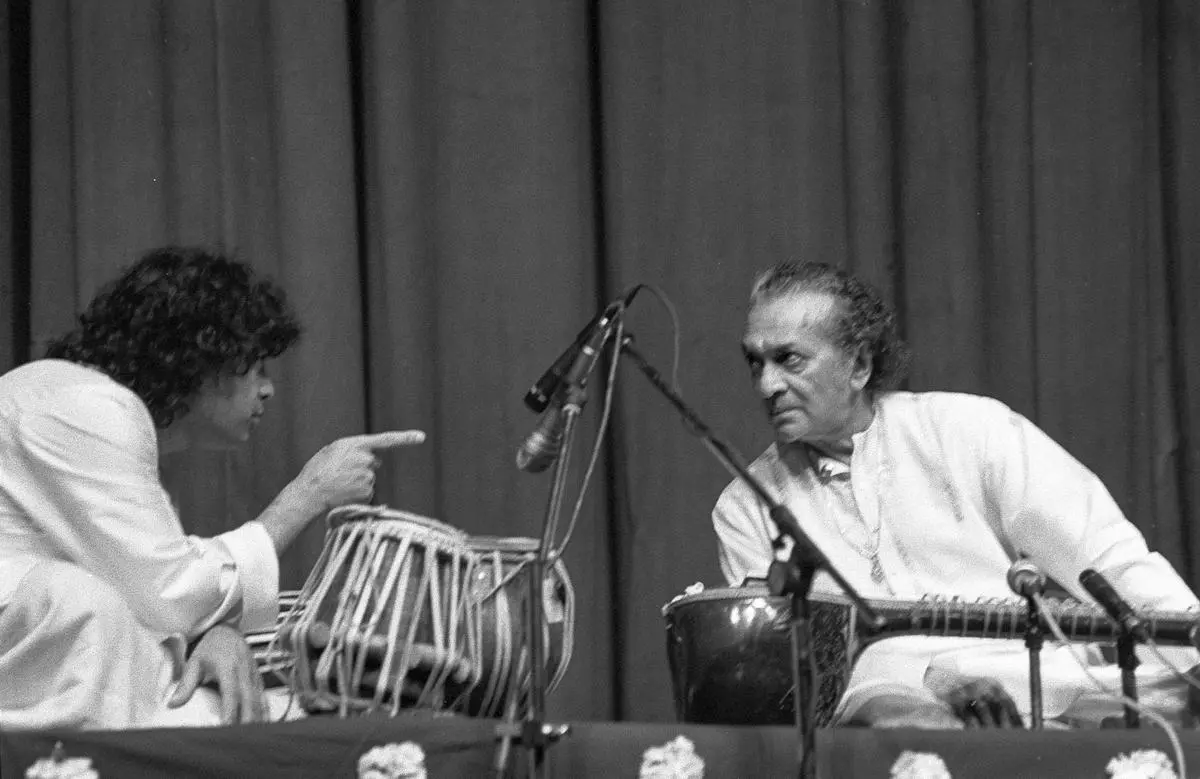

Zakir Hussain performs with sitar maestro Pandit Ravi Shankar in New Delhi. A file photo.

| Photo Credit:

PTI

The Ustad that he was, Hussain, throughout this first piece made sure that the sarangi was equally foregrounded and never used it as a mere lehra accompaniment. What was striking was how he took in the inherent melody of the sarangi into his own playing. One notices this even in the album for which he composed music, Music of the Deserts (1993), and in a way, one could see a continued journey that evening. The Ustad’s percussion shone with an innate melody.

Even in a concert of such a nature, where plan and precision are most crucial, the intuitive self of Hussain was constantly alive. He brought unpredictable moments into the performance, which only an Ustad like him could execute. The 16-beat pattern is common to both Carnatic and Hindustani styles, the stresses and the highs and lows are unique to each system. In a fusion concert, it took a sensitive musician like Hussain to enhance these differences and not distort them. His brilliance coupled with flamboyance, was a combination that was hard to resist.

Ustad Zakir Hussain is no more. The lyrics of his favourite song “Salamat Raho”, for which he played the tabla (in the 1963 movie Parasmani) plays in my mind. “Roshan tumhi se duniya.. raunaq tumhi jahan ki … Salamat Raho [From you, there is light in the world, from you the world shines… May peace be with you].”

Deepa Ganesh teaches at RV University, Bengaluru.