The aviation industry gave wings to humanity’s dreams of flying. For a little over 100 years now, the world has been better connected than ever before as aeroplanes have linked the lands and skies with ease. These same aeroplanes also enabled early aviators to show that it wasn’t just the lands and skies, but also the skies and seas that could be joined. The first such demonstration was carried out by American aviation pioneer Eugene Burton Ely.

Born in Williamsburg, U.S. in 1886, Ely grew up in Davenport in Iowa. He attended local schools before going on to obtain an engineering degree from the Iowa State University in 1904. Drawn towards mechanics, Ely began his career in the automobile industry, working as a salesman, mechanic, and race driver.

Teaches himself to fly

Ely taught himself to fly in 1910 and took to these crafts like a duck to water. He, however, had an unusual beginning. When an auto dealer in Portland bought a Curtiss biplane and was afraid to fly it, Ely offered to try… only to royally smash the plane. Embarrassed by this turn of events, he bought the wreck from the agent, repaired it and taught himself to fly in the following months.

Exhibit in the Hiller Aviation Museum, San Carlos, California, showing Ely’s pilot license.

| Photo Credit:

Daderot / Wikimedia Commons

Ely encountered aviation pioneer Glenn Curtiss during one his flying meets and it served as a turning point in his fledgling flying career. Always on the lookout for promising talent, Curtiss knew one when he saw one and signed Ely on as a member of his exhibition team. What followed were a series of air shows as the Curtiss team criss-crossed the country, promoting Curtiss planes and showing them to be better than their rivals.

Chambers’ offer

In that same year, the Navy had identified Captain Washington Irving Chambers “to observe everything that will be of use in the study of aviation and its influence upon the problems of naval warfare.” In order to keep himself abreast with aviation matters, Chambers attended one of the flying meetings being held at New York in October and encountered both Curtiss and Ely. While there was no money for such a proposition, Chambers said that he would be able to provide a ship should someone be willing to attempt a take-off from its deck. Finding the proposal tantalising and excited at the prospect, Ely readily agreed.

November 14, 1910 turned out to be a gloomy Monday and the afternoon had intermittent rain showers. Ely got onto his Curtiss Pusher aircraft that was mounted on an approximately 80-foot long wooden platform erected on the bow of the light cruiser USS Birmingham. The short runway meant that there was very little room for error and also quite a short distance before Ely had to take-off.

Ely barely managed it, but the first take-off from a ship was a success. Plunging down after clearing the ship’s bow, Ely’s craft settled before its wheels dipped into the water before rising. While the propeller was damaged and Ely’s goggles were covered with the spray, he managed to stay airborne. Spotting a stretch of beach just ahead, Ely landed just 4 km from where he started, having created history.

Ropes, sandbags, and hooks

It was one thing to take-off from a ship, but quite another to land on it as the question of arresting the momentum of the craft still loomed large. The San Francisco area was caught up in a frenzy of air exhibitions in January 1911 as a number of records were broken day after day.

Even though he had just managed the take-off, Ely was willing to attempt the landing. Chambers, aware that Ely, Curtiss, and the team were flying in San Francisco, made the necessary arrangements for an attempt on the west coast.

July 1911 picture showing a plane piloted by Ely flying over a naval ship.

| Photo Credit:

Museum of History & Industry (MOHAI) Seattle / picryl

With a longer platform of about 120 feet this time, the armoured cruiser USS Pennsylvania was anchored in San Francisco Bay. The tailhook technique that was to be employed for the first time meant that an arresting system for landing was put in place by stretching ropes with sandbags in the platform. If these failed to do their bidding, there was a canvas at the end to catch the plane.

Ely-mentary flying

As for Ely, he wore an American football helmet on his head and bicycle inner tubes around his body for the worst-case scenario. His craft had longer wings and the landing gear sported hooks to latch on to the ropes on the ship. Watched by crowds lining up the shore and boats in the harbour, Ely took off at 11 a.m. on January 18, 1911. The arresting technique worked perfectly and Ely landed safely to the delight of all the onlookers.

Ely made it look easy, but those around mobbed him when he had successfully pulled off the feat of landing a plane on a naval vessel.

| Photo Credit:

Mjr Kool / flickr

Following lunch with the ship’s captain and some photographs, Ely prepared for the return trip. With crowds still thronging the Bay Area, Ely made it look easy, taking off successfully and landing back safely where it all started. Naval aviation was born as landing and take-off on the same day had been achieved for the first time.

Fulfils his own prophecy

This demonstration made Ely a bigger star than what he was already and the months that followed were a whirl of activity as he flew at various meets and exhibitions. When questioned about his retirement from being a show pilot as he had amassed enough wealth, Ely replied philosophically, saying “I guess I will be like the rest of them, keep at it until I am killed.”

It happened sooner than later as Ely lost his life during a show in Macon on October 19. Having misjudged the distance from the ground while plugging downwards, his craft continued downwards instead of levelling off and coming out of the dive. While Ely did manage to jump off his craft, he broke his neck in the process and died minutes later.

Recognising his achievements, the Navy awarded him the Distinguished Flying Cross posthumously in 1933. Ely’s flying career had lasted for less than two years, but he’d changed the face of naval aviation in that short span.

Robinson’s tailhook

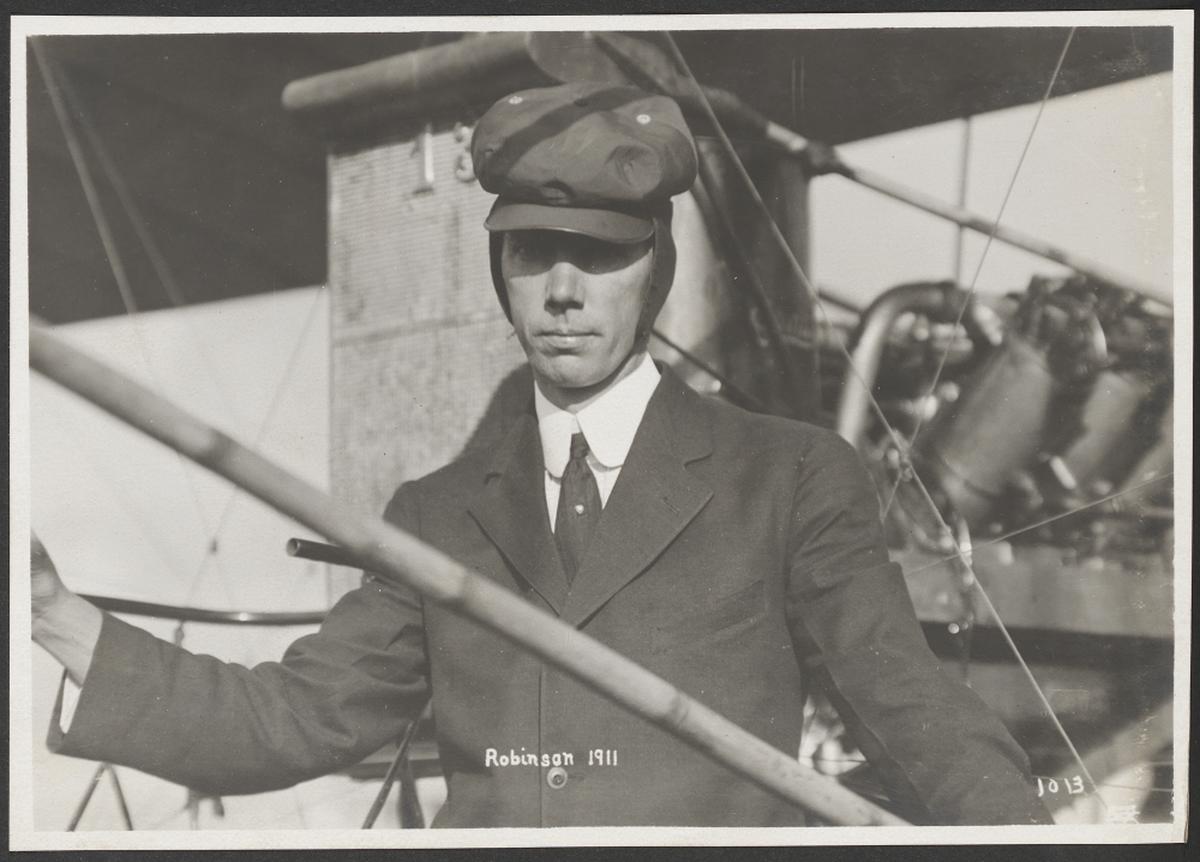

Hugh Armstrong Robinson, early aviation pioneer.

| Photo Credit:

SMU Libraries Digital Collections / Wikimedia Commons

Even though Ely is best remembered as the man whose flights gave rise to the birth of naval aviation, his deeds were made possible by another American aviation pioneer, inventor, and engineer, Hugh Armstrong Robinson.

Robinson was the inventor of the tailhook that enabled aeroplanes to safely land on the deck of a ship. As there was no way to help the deceleration process and stop the aircraft in time after landing, the invention of this device was critical in the birth of naval aviation.

The technique that Robinson envisioned and implemented for Ely to succeed in his landing atop a naval vessel was so successful that it remains in use even today, albeit with enhancements appropriate to our day and age.

Apart from inventing the tailhook, Robinson had plenty of other claims to fame. Living at a time when many aviation firsts were unleashed, Robinson too had many to his name. He is usually credited as the first to carry out a right turn in an aeroplane, a manoeuvre thought to be very difficult at the time. Other firsts included designing and piloting a hydroplane, attempting the rescue of someone at sea using a plane, flying the first medical flight (a doctor was flown to care for a young boy who had broken his leg), and even flying authorised mail deliveries!

Unlike many others who saw 13 as an unlucky number, Robinson saw it as a very lucky number. While this could be partially because of his birthdate (May 13, 1882), it could also be because he once earned $1313.13 as prize money after flying for 13 minutes. Whatever the reasons, Robinson put the number 13 on all of his planes.

Published – January 18, 2025 11:52 pm IST