Zakia Jafri, who fought an over two-decade-long legal battle to secure justice for the victims of the 2002 Gujarat riots, died at the age of 86 in Ahmedabad on February 1. Her husband, former Congress MP Ehsan Jafri, was among the 69 people who were killed inside Gulberg Society, a Muslim neighbourhood in Ahmedabad, during the riots.

“Out of hundreds of Gujarat cases, Zakia Jafri’s was the one that insisted: this wasn’t just a personal tragedy, it was an attack on an entire people,” Zara Chowdhary, the author of The Lucky Ones: A Memoir, told Greeshma Kuthar. In a freewheeling conversation, Chowdhary and Kuthar discuss Zakia Jafri’s struggle and legacy, the erasure of collective memory, and Chowdhary’s book set during the 2002 riots, among other things. Excerpts:

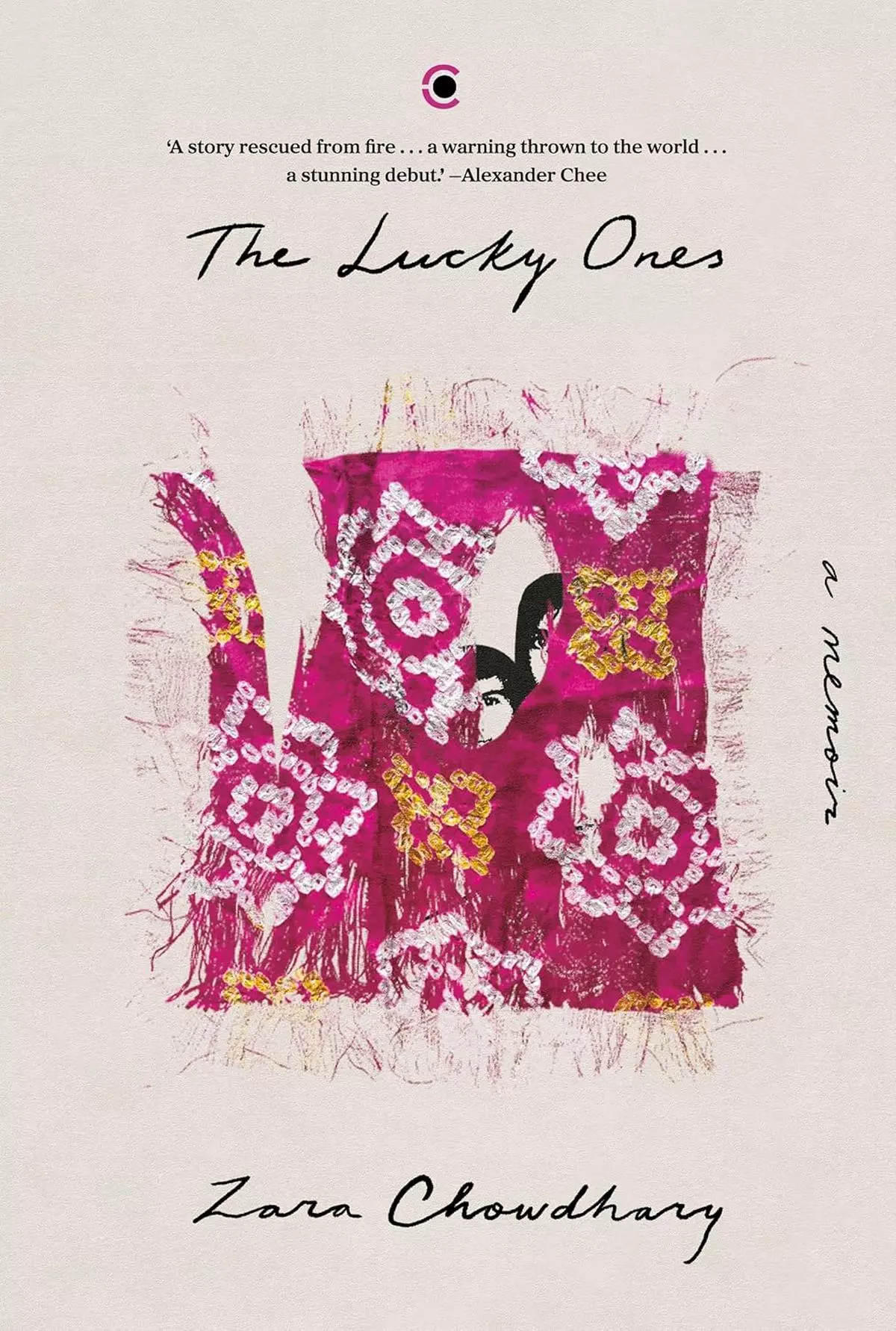

Welcome, everyone, to this conversation with Zara Chowdhary—a writer, professor, and, most importantly, the author of The Lucky Ones. It’s called a memoir, but it is a blend of different writing styles; memoir, journalism, fiction, and nonfiction. It’s essential reading. There’s a review in this month’s Frontline, so you can check that out before picking up the book.

I want to contextualize this conversation. While we’ll be discussing Zara’s book, we’re also remembering the late Mrs Zakia Jafri, who recently passed away. Zara, thank you for joining us. This conversation will be difficult, just as your book was a difficult but powerful read—perhaps the most powerful memoir I’ve encountered in years.

To start, in one of your pages, you write: “My childhood was a pogrom in progress.” That line stood out to me. Throughout your book, you navigate that phase with remarkable empathy, even when writing about perpetrators. You analyse the institutional forces that shape them, which is an incredibly difficult process.

It reminded me of a meeting in Gomtipura after the Una violence in Gujarat, where Muslims and members of a Scheduled Caste community were reconciling. Some of them had been part of the violence, yet I witnessed both sides engaging in a process of empathy, similar to what I see in your book. Why was that perspective so important for you—not just in addressing violence and perpetrators, but even in reflecting on your own family?

Thank you. I appreciate how you see people beyond the things that happen to them. That perspective is key—whether in journalism, memoir, fiction, or even painting. If we’re not first seeing the human in someone and situating them within a broader world, then what are we doing?

Placing myself at the centre of this story forced me to recognise that I, too, am a product of this place. As women, we spend much of our early lives struggling to define ourselves. In adulthood, it becomes easy to settle into an idea of who we are. But memoir peels away those layers. It forces us to see how the world constructs us. If I can do that for myself, why wouldn’t I extend the same to others? I’m not sure if empathy is the right word—it feels more like an exercise in being human.

We live in a world where therapy and mental health discourse are widely used to explain ourselves or diagnose others. We hear terms like narcissist or problematic, but we often fail to acknowledge how our environments and experiences shape us. Violence isn’t just a pogrom—it’s the slow, insidious harm embedded in our communities, in India and beyond. That’s why I wrote this book: to immerse myself in that uncomfortable process. Writing is an act of pushing yourself beyond what you’ve been allowed to be.

WATCH | ‘Zakia Jafri was more than a widow seeking justice’: Zara Chowdhary

The author of The Lucky Ones says Jafri’s quest for justice for the victims of the 2002 Gujarat riots was testament to how she carried others along.

| Video Credit:

Interview by Greeshma Kuthar; Editing by Samson Ronald K.; Produced by Abhinav Chakraborty

I want to read a passage from your epilogue:

“Our idea of India and being Indian Muslims, as we learned it through Dada, Papa, Amma, through blood, land, and spirit ancestors, through teachers who taught us and strangers who saved us, gave us a quote to live by: The pursuit of justice at all costs. My home is this memory I hold of India, of who we once were. And my uprising is to keep the story writ into history, no matter how much erasure stamps over it.”

This passage, in the context of both your life and Mrs Zakia Jafri’s, raises a question. When your existence is marked by the denial of institutional justice—something that should be a given—where does a persecuted group find justice? You say your uprising is to write this story, to leave it as a testament. How do you see justice in your life and in Mrs Jafri’s journey?

I’ll start with her. I only knew Zakia Ma’am from a distance, particularly in the later years of her life when she spent time in the US. Every February 27th and 28th, I would think about what must be going through her mind.

For us as Muslims, the concept of Haq—justice—is deeply tied to our faith. We believe that ultimate justice rests with Allah. Martin Luther King spoke of the moral arc of the universe bending toward justice, and I see a similar theological grounding in so many persecuted people. Sometimes, human institutions are too small, too petty, to offer true justice. So we turn to something greater.

That’s why we have terms like “Supreme Court”—because it is supposed to be the final authority on justice. But for us, true justice resides in “Allah ka darbar”, not in the halls of human institutions that have been co-opted. What Zakia Jafri did—knocking on every door for over 20 years—was a testament to her faith. If you believe that Allah will give you justice, then the burden shifts. You no longer rely on human systems; you simply fulfill your duty by showing up and knocking on doors. Whether they open is not up to you, but you keep knocking.

Her legacy—and the legacy of others like her—feels like mine. These are my elders, and they teach me that life is about persistence. Even writing this book for seven years was crushing, especially while watching things deteriorate back home. Every day, another trauma surfaced on social media. There were days I curled into a ball and wept. But something always pulled me back to my desk.

Zakia Jafri was more than a widow seeking justice. She was a mother, a grandmother, a community member. She carried others with her. That reminds me of a story my friend Zehra Mehdi shares about the Shia tradition of demanding justice. Hazrat Zainab, daughter of Hazrat Ali and granddaughter of Prophet Muhammad, survived the massacre of her family. She stood before the tyrant who had slaughtered them and demanded justice—not just for her personal loss, but for her entire community. That distinction is crucial.

In marginalised communities, we never carry our burdens alone. Dalit liberation movements embody this as well—you walk with your entire community. Out of hundreds of Gujarat cases, Zakia Jafri’s was the one that insisted: this wasn’t just a personal tragedy, it was an attack on an entire people. That difference—seeing oneself as part of a larger struggle—is what fuels me. I am not writing alone. I am not walking alone. Even the dead are with me. And whatever comes, it comes for all of us.

Zakia Jafri, who fought an over two-decade-long legal battle to secure justice for the victims of the 2002 Gujarat riots, died at the age of 86 in Ahmedabad on February 1.

| Photo Credit:

PTI

But when we think about what she did—taking on some of the most powerful people in the country, from the current Prime Minister to celebrated State leaders—and compare that to your work, this book stands as testimony, a memoir of everything. I understand when you say the depth of this work comes from carrying your community forward.

But that weight is immense, isn’t it? There’s a personal reckoning involved in this journey. I feel like that aspect isn’t discussed enough—you are just one person, after all. Writing this book, documenting all of this since childhood, making your adulthood about this act of documentation—it’s remarkable. I’d love to hear about your personal journey in getting to this point. What were the challenges you faced? Because I see a parallel with the immense difficulty of Mrs. Jafri’s journey.

Thank you for that. It’s kind of you to say, but I feel uncomfortable with the idea that I’ve done something monumental—because I haven’t. Nothing in this book, especially the sections on violence, is based on my first hand account. Everything has been reported multiple times. For any news item I chose, I can point to five sources that have covered it. At times, I felt like a grifter—there’s an abundance of information, yet no real reckoning as a community or country. My job became that of a weaver, knotting existing threads together into a pattern that makes the scale of a pogrom undeniable—not just its impact on one community, but on the entire nation.

On a personal level, when you read the book, you’ll see that I come from a violent home—emotionally, physically, patriarchally. But we live in a world where speaking my truth about my family could reflect poorly on my community. It could be used to further criminalise men from my community. As much as that story was lodged in my throat, I couldn’t afford the privilege of telling it in isolation—just another middle-class Muslim family in a building, living their daily lives. We’ve seen novels and memoirs take that approach, but I didn’t have that liberty.

That’s exactly what I mean—writing this book wasn’t just about documenting violence. You made a deliberate choice to bring in personal elements, despite knowing the risks. That must have made the journey even harder. Even if you say there were multiple sources, the act of centring your story and weaving it together in this way couldn’t have been easy.

At most times, it felt like so much had gone into making me who I am. And not just in terms of lived experiences—so many people, collectively and individually, have contributed to my writing journey. When I sat with this book, balancing my family’s story on one side and the country’s violence on the other, I reminded myself: I’ve had 15 to 20 years of training, funded and supported by grants, mentors, people encouraging me to keep going.

If I don’t put that craft in service of making this undeniable, then what is it for? Our stories are so easily dismissed if they lack craft. That became my challenge: ensuring that when I wrote about my father, Ehsab, Sunil, Bilkis Bano, her daughter—any of them—I did so with technique, with precision, to restore some of the life stolen from them. My only job was to hold them in a way that made them real for the reader. That was the question I kept asking myself: What is my job in this? Because when things get hard, it’s easy to crumble. I had to remind myself—this is what I trained for.

Also Read | The rise of the Hindu Right

And that technique is evident throughout. When I think about your use of memory as a technique, I recall the story of Wali Gujarati’s resting place. And the unmarked graves of those who died in the 2002 massacre. There is a correlation that I want to draw between both these references. But the way you connected the story of Wali’s dargah, and that to your grandfather’s memory, your family, and ultimately yourself—it’s powerful. Thank God for the craft you nurtured, allowing us to take this in as we read. But this is also a test of memory, isn’t it? You mention people walking down that road to the dargah, searching for a marker, not finding it, leaving petals instead. How do we, in a country so determined to erase memory, treat it with the dignity it deserves?

That whole section was one I fought to keep in the book, even with my editor. I don’t know if you remember, but I list the steps for a Muslim burial there.

Yes.

In that section, I juxtapose the unmarked graves of massacre victims with the marked graves of my own family. There was debate over keeping it—on the surface, it doesn’t seem to “say” anything beyond detailing burial rites. But India is a deeply ritualistic country—every microculture has its own strict traditions. One of the most traumatic aspects of death here is how rituals either overwhelm grief, robbing it of quietness, or suppress it entirely, preventing true mourning. Islamic rituals, as I experienced them growing up, fell into the latter category—after three days, we were told not to cry, that it would hurt the departed’s soul. I believed that for years. But what does that do? It steals the right to process grief.

For me, whether it was my grandfather’s death, my father’s death, or the mass deaths of 2002, that grief remained unprocessed. Writing those sections was my way of grieving—publicly, but with the quietude of the written word. I wanted to walk the reader through every step: how the body is washed, how it must face Makkah, how it is shrouded. But what of those denied these rites? Those violently taken, their graves erased? Wali Gujarati’s tomb, paved over. Most Indian dargahs, bulldozed as we speak. The dignity of the recently dead is stolen, yes—but even the long-buried are being uprooted. That theft is ongoing.

Right.

And there’s something to be said about the impulse that drives people to do that. I question it. I question what makes someone pull another from their resting place and desecrate them. We’re seeing this in Gaza right now—bulldozers and rollers running over cemeteries. What is that idea? This has happened in the US too. Half the Halloween movies here revolve around houses built over desecrated graves.

“People have lost their ability to process how societies and politics are built. Look at Gujarat: 2002 happens, people stop paying attention, and a decade later, the same figures are in power. That lapse of attention is what allows things to escalate.”Zara ChowdharyAuthor, The Lucky Ones: A Memoir

Seeing graves being unearthed and burned in Manipur—it was shocking for me. And you just don’t understand it.

Exactly. That kind of shock stays with you, especially as a young person. You witness what makes human beings lose their dignity—because in desecrating others, they indignify themselves. They think they’re showing disrespect, diminishing you, but they’re really doing it to themselves. That’s what fascinates me, in a morbid way. What drives people to do that? How deep does your hatred have to go? How completely consumed must you be with the need to break the other that it makes you into this? Are you even human after that? That, for me, is the burning question.

Cover of The Lucky Ones: A Memoir.

That reminds me of some of the characters in your book. One is Preeti Ma’am, whom you remember fondly. But the other is your friend, the one who calls you after a long time and casually asks, “Let’s go for a movie,” in the middle of a curfew. That contrast—how you juxtapose characters—is striking. You show non-Muslims in different lights: some violent and unapologetic, carrying on as they have for decades, from 2002 to now. But then there are people like your friend—not ignorant, but choosing to pretend they don’t know what’s happening. That’s such a crucial aspect of your writing. You’re not just recounting a memory, but urging people to examine that attitude—this silence, this indifference.

Yes.

When you wrote about that friend, what were you feeling? What did placing her in the book mean to you?

These aren’t just characters. They’re real people. And over the last twenty years, that story has taken on more weight than it had at the time. Back then, it was personal hurt—someone I went to school with every day, someone who knew what I went through at home, even before the riots. Teenage friendships are vulnerable. They have this intimate, privileged window into your life. But just because she lived across the river—in the modern part of the city, with good roads, big malls, a McDonald’s—there was an immediate divide.

And that part of the city had the sympathies of Gujarat’s Hindu legislators.

Exactly. In that moment, I realised that to her, I was just an instrument of friendship in school—a forced secular space where civility was expected. But the minute our geographies separated—me in the old Muslim ghetto, her in the swanky Hindu part—the window shut. And I think about this in other places, too: in the West Bank, where walls physically separate people, or in Ahmedabad, where they built a wall so Trump wouldn’t see the slums. But more than physical walls, I wonder about psychological walls. The instant they have to engage their conscience, the wall comes down. And that’s something I’m always testing—what makes that wall fall?

Because this is the question we’ve been asking from the beginning: empathy. Why is it that I can see you with empathy, yet in that moment, you question my reality? You call me and say, “Oh, but everything is fine.” Even today, I meet people from Ahmedabad who say, “The violence lasted three days.” They’re in their 40s, 50s, writing to me, saying, “We’re so sorry. We just didn’t realise what was happening.”

“We didn’t realise.”

And that’s what fascinates me. When I moved south, I saw how much more connected communities were compared with Gujarat. A pogrom of that scale couldn’t have gone unnoticed in a place like Chennai. But Ahmedabad was a testing ground for an ideology. When we say Gujarat was a laboratory, this is what we mean—not just geographical division, but ideological division, right down to children.

I wrote about a Jain boy I knew. We used to watch cricket matches at his house. He was six or seven years old; I was in seventh grade. One day, I wore a mint-green T-shirt, and he said, “Pakistan colour.”

My first reaction was pure rage. Who gives you the right? You’re six. You’re speaking to someone older like this? It wasn’t even about nationalism for me in that moment—it was just the sheer disrespect, the training that had gone into that child. Because it was training. He had been taught this. He had learned that this is how you address a Muslim, how you denigrate them. The children were being shown, by their elders, how to humiliate us.

And that’s the reality we’re living in now. These walls aren’t just in one city. If you look at everything that’s happened since 2002, or since Babri Masjid, or for decades—it’s always the same. Something happens, and the rest of the country is oblivious. And as the years pass, that gap only widens. Look at Manipur. People just looked away. Even after seeing it, they chose to look away. The government wants you to look away. And how is that possible?

We’re living in an age of maximum distraction. Our attention is the most valuable commodity—corporations spend billions to capture it. Ten seconds on a reel, 15 seconds on another app, a new movie, an online sale—everything is designed to pull us away. But the realities haven’t changed. The dissonance is staggering. People have less patience for social realities because it feels like an inconvenience. As if telling these stories is an imposition.

Right.

But these stories affect them whether they like it or not. You could be in Bangalore, but what happens in Manipur affects you. You just don’t see the connections anymore. People have lost their ability to process how societies and politics are built. Look at Gujarat: 2002 happens, people stop paying attention, and a decade later, the same figures are in power. That lapse of attention is what allows things to escalate.

It wasn’t always like this. I don’t know your age, but I grew up in the Doordarshan era. News was always on in our house—not just background noise, but actively consumed. There were newspapers in multiple languages. We wanted to know what was happening in our street, our State, the world. That curiosity has vanished. Now, people perform awareness—Black Lives Matter means a black square on Instagram, Palestine means a few trending hashtags. But in their own cities, they’re blind. They don’t know that Muslims are being denied homes or jobs. They’re unaware of the discrimination in front of them. They’ll talk about Palestine but ignore Gujarat. It’s an upside-down world.

It’s ignorance, yes, but it’s also acceptance. A belief that “this is just their reality”. That Muslims, the lower class—this is simply how they live. And there’s only so much thought I’ll give it. Only so much attention I’ll grant it.

Right.

Also Read | Do Muslims need to change their approach?

You know, I feel like we’re at a point where people have access to more information than ever before. In the past, when there was only one news channel, that was your only source of news. But now, news is literally at your fingertips. And yet, people still choose ignorance. What does that say about us—about our collective response to social realities? That’s what can be so disillusioning for many journalists, including myself. How do you respond to that? How do you process this widespread attitude of choosing numbness, as if that numbness somehow justifies ignorance? You know what I mean?

Right. That’s actually really interesting. I was just reflecting on this a few days ago. Writing this book has made me think about it even more. Before 2002, when I was in high school, we studied the Holocaust. I remember being obsessed with understanding it because, to my young mind, it was incomprehensible that humans could go to such extremes to annihilate an entire community—using advanced, systematic, technological means. It was a shock to my system, and I needed answers. I kept asking: how could this happen on a global stage, and how did no one intervene?

Then, just a year later, the pogrom in Gujarat happened. By then, my mind was already traumatised, but that trauma didn’t stop me from reading more about the Holocaust. If anything, it intensified my need to understand it—and other genocides. I kept searching for meaning, for patterns, for something that could explain what I had witnessed.

Since my book was released in India last year, I’ve heard from readers who’ve passed it on to others. But I’ve also heard, multiple times, people say: “I’ve been trying to get my friends to read it, but they say it’s too depressing.” And my usual follow-up question is: what is their identity? Because I’m curious—if you’re not Muslim, Dalit, Adivasi, or someone who has personally experienced systemic injustice, what is taking up so much of your time and attention that you can’t engage with what’s happening in your own country? What are you so busy with?

This attitude of “the world is already too depressing; I can’t handle more” baffles me. If you’re not even curious about why the world is so bleak, how do you expect it to change? It creates this strange loop where people want the world to magically fix itself without confronting the structures upholding oppression. So I say, fine, don’t read my book—read something else. But how are you not curious?

That’s a powerful question. And I think it’s the perfect note to end this conversation on. Because at its core, this isn’t just about reading your book—it’s about responding to everything happening in India and beyond. Thank you so much for talking to Frontline.

Greeshma Kuthar is an independent journalist and lawyer from Tamil Nadu. Her primary focus is on investigating the evolving methods of the far right, their use of cultural nationalism regionally, and their attempts to assimilate caste identities into the RSS fold.