It’s just before Christmas, and customers intermittently stream inside Vaporio, an alternative store that sells herbal remedies and vape supplies in Ocean Springs, Mississippi. They’re greeted by the Malosh family — 28-year-old Trevor, 50-year-old Tracy, and 53-year-old Charles.

They talk holiday plans and Christmas gifts with customers. Remind folks when they’ll be closed. It’s a small town. Everyone knows each other.

The Maloshes started the business after Charles retired from Verizon in 2019. It was their dream. The three of them could work together. Spend more time as a family.

It also served a practical role. Trevor was born with a condition called aortic stenosis. Sometimes called a failing heart valve, it can cause symptoms like tiredness, weakness and dizziness. With the family business, Trevor could work according to how he was feeling.

But when Charles left Verizon, he also left behind the health insurance plan that covered the family. Through the business, they were able to purchase coverage through the Mississippi Marketplace. They chose a plan from Molina Healthcare, an insurance company based in Jackson that covers 5.1 million people.

Having health insurance was critical for Trevor. He’d had surgery to replace one of his heart valves when he was nine. Everything had been going well since then, but they knew that one day, Trevor would need to have the valve replaced.

“I’ve considered my condition a ticking time bomb because I knew at some point, I would need surgery,” Trevor said. “So for the last 20 years of my life, I’ve had it in the back of my mind. I knew this was coming up. Did I know it was going to happen this year? Absolutely not.”

In June, Trevor started to feel worse. He was more tired, weaker. He found himself getting dizzy more often and sometimes feeling like he might pass out. He went to his cardiologist, who told him the time for a new heart valve had come. His doctor recommended a surgeon at Ochsner Health in Louisiana, about an hour away from Ocean Springs. Soon after, the Maloshes made a consultation appointment with Dr. Benjamin Peeler, a cardiothoracic surgeon.

This is where their troubles began.

They would spend months going back and forth with the insurance company and the hospital trying to get the surgery approved. And even when they managed to get Molina to agree to pay for the surgery, they’d run into another obstacle: Ochsner refusing to do the life-saving operation.

Their experience navigating narrow health care networks, experts say, is not uncommon.

Ochsner isn’t part of Molina’s network — the list of approved doctors and hospitals the insurance company will pay for. When the hospital ran their insurance, Molina quickly denied the initial consultation. The company has a 24.2% denial rate in Mississippi, according to 2021 data from KFF, a health policy research group.

Ochsner Health declined to respond to questions for this story, saying in a written statement that the hospital system is “committed to delivering the highest quality care to every patient we serve. In adherence to federal and state privacy regulations including the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), we are unable to disclose specific information regarding any individual care plans.”

Molina Healthcare agreed to take questions from the Gulf States Newsroom but did not respond further.

Trevor’s secret weapon

Hospitals and health insurance companies have their own conversations where they work on getting procedures approved and reimbursed. These negotiations often occur behind-the-scenes, without patients even knowing about them.

But Trevor had a secret weapon: his mom, Tracy, a former nurse.

Through Tracy, the Maloshes made themselves part of these backroom dealings, contacting Molina and Ochsner almost every day. They said it was like a full-time job. As Trevor started to feel worse, he’d need to take more time off. Sometimes, Charles would run the store by himself so Tracy could stay on the phone with the insurance company and communicate with the hospital.

Tracy knew it would be a fight, but she was prepared to do it. Trevor’s condition is what inspired her to become a nurse in the first place. Trevor collapsed while rounding the bases during a little league baseball game and had his first open-heart surgery in May 2005 — three months before the family lost everything during Hurricane Katrina.

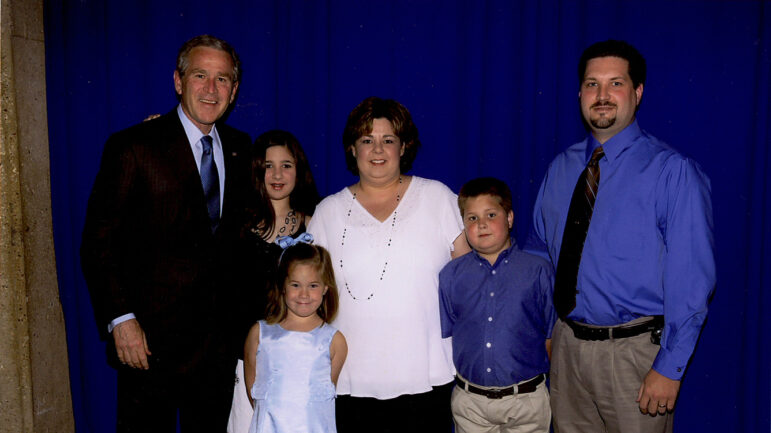

Despite the hardships, Tracy persevered and graduated from Mississippi Gulf Coast Community College in 2006. Her story was so inspiring, then-President George W. Bush, her class’ commencement speaker, called her out by name and took a photo with the family after the ceremony.

In the picture with Bush, Trevor’s face is swollen from steroids he was taking to help fight off infections, his body still healing from the operation.

After Molina denied the initial consultation with Dr. Peeler at Ochsner in October, Tracy went to work. The Maloshes appealed the denial and were eventually able to get the appointment approved. After meeting with Dr. Peeler, they scheduled a surgery date for November 18 to get it on the books. Then, they shifted their focus to getting the surgery approved.

This turned into near-daily conversations with Molina and Ochsner. Tracy knew that what they needed was called a “single-case agreement” — essentially, a one-time-only contract between an insurance company and an out-of-network medical provider. The family fought for this.

At one point, Molina told the Maloshes that when Ochsner submitted their request for approval, the nurse did not check the “single-case agreement” box on the form. Tracy sent a message to the nurse at Ochsner, pointing out the error.

“I understand mistakes are made,” Tracy wrote in a portal message, “but today we were told by [the nurse] on the phone that Trevor’s condition is low on the spectrum of congenital issues, and getting approval for a specialized surgeon would be difficult.”

Afterward, the family said they felt as if the tone was starting to shift in these conversations. They got the sense the hospital and the insurance company didn’t appreciate their advocating for themselves.

“We did get a lot of backlash from my mom making phone calls,” Trevor said. “I’m lucky in that regard. I have a mom with a medical background that’s been in the hospitals. Not everyone has that. So I’m definitely going to let her help me. I’m not going to try to do this alone.”

Tracy was eventually told she could no longer communicate on Trevor’s behalf unless she had a power of attorney. So she got one, and they continued to work to get the surgery approved.

On October 15, after weeks of back and forth with Ochsner and Molina, Trevor received a note from a nurse at Dr. Peeler’s office through the hospital’s messaging portal that they believe was intended for another hospital staff member and was erroneously sent to them.

“I’m happy to cancel the preops and surgery whenever you give me the greenlight,” the nurse wrote.

Tracy responded in the portal: “WOW.”

The Malosh family provided the Gulf States Newsroom with copies of their portal messages for review.

An ‘exhausting’ battle

While they worked to get the surgery with Ochsner approved, Molina sent the Maloshes a list of in-network providers.

Many of these doctors were cardiologists who could not perform cardiothoracic surgery. In response, the Maloshes sent the definition of cardiologist and the definition of surgeon to the insurance company, explaining the difference.

Trevor also tried to follow Molina’s recommendations. On October 29, he sent his records and made an appointment to see a heart surgeon that was in Molina’s network at a Singing River Health System hospital in Ocean Springs. The hospital said the surgery was beyond their scope of care. The chief medical officer at Singing River wrote a letter to the insurance company.

“After reviewing the medical records provided and speaking to the surgical team, we believe it is in the patient’s best interest to receive treatment at a facility with a higher level of care,” the letter stated. “We recommend a program and Cardiothoracic Surgeon that has more experience in surgical cases like the one required for Mr. Malosh.”

In the meantime, Ochsner told them they’d need to “bump” the surgery date until they could get approval for it.

But Trevor’s symptoms continued to worsen. He was sleeping most of the day. He was having trouble working. He almost passed out in a parking lot.

The situation was also impacting the family’s livelihood. They had to close their business when they’d go to appointments or when they were too focused on calling the hospital and insurance company. With each closure, they’d post on their Facebook page, letting their customers and community know. Everybody was aware of Trevor’s condition and supportive of the family’s fight to get him the surgery he needed.

They said the stress of the battle for approval was “exhausting.”

“I wasn’t expecting this much backlash for something that I’m not choosing to do. I don’t have a choice. This has to be done,” Trevor said. “These people act like I don’t need it. To me, it feels like it’s more about money than my health. And that’s what’s upsetting.”

In the first week of November, Trevor finally got some good news. Molina called to tell him they’d established a single-case agreement and the surgery had been approved. The Maloshes were overjoyed.

“You’re going to get white glove service, exact quote,” Tracy said. “Awesome. Oh my god, I’m crying. I don’t know what to do. I’m calling everybody. We’ve been approved. It’s on. We’re going to get it, now we just got to get a date.”

The Maloshes contacted Ochsner to let them know, but were soon met with another roadblock. A nurse with the hospital informed them they could not move forward with Trevor’s surgery.

Tracy was devastated.

“I just sat there and I was like, ‘What?’ Tracy said. “I started crying. I used the f-word. I hung up on her. I had to go sit outside. And I said, ‘I do not understand what has just happened. I do not understand this at all.’”

Navigating narrow networks

Since that call, the Maloshes say Ochsner has yet to respond to them.

They’ve since tried to contact outside parties, hoping for any sort of help. They called Mississippi Gov. Tate Reeves twice, but said they’ve yet to receive a call back. They’ve also contacted the Mississippi Insurance Department (MID), which helps residents struggling with health insurance issues. They said MID told them to keep their Molina coverage and find a cardiac surgeon in the company’s network who can perform the operation — to start the process over.

What the Maloshes have experienced — the rigmarole of navigating the approval process for insurance companies and hospitals — isn’t unique. Part of the problem is Molina’s narrow network of providers approved by the company.

Many exchange plans try to steer patients to particular providers that have better rates to allow the insurance company to control costs, said Becky Greenfield, an attorney at Wolfe Pincavage law firm, which represents hospitals in their relationships with insurance companies.

“What’s glaring to me in all of this is the network inadequacy of the plan,” Greenfield said. “This happens a lot with exchange plans like the one that Trevor was covered by.”

Ruth Landé, vice president at Undue Medical Debt, a nonprofit that helps people struggling with medical bills, also said Molina’s network is a large factor in the Maloshes’ struggles.

“Sadly, I was not shocked by how much work and how hard it was for this family to get an out-of-network authorization for this care,” Landé said. “They did all that incredibly hard work, that didn’t surprise me. And then they got it. Fantastic.”

Landé said what stands out to her in the Maloshes’ case is the fact that the hospital, Ochsner Health, then refused to do the surgery after Molina approved it. She said she actually “yelped” when reviewing the records for this story.

“I was shocked that the surgeon didn’t agree to go ahead with the surgery,” she said. “I don’t understand that at all. That’s bizarre. I don’t get it.”

In response to questions for this story, an MID spokesperson wrote that, “In the event an in-network facility does not have a physician to perform a medically necessary procedure, insurance companies have an obligation to their insured to afford coverage and seek care out-of-network. Once this occurs, the out-of-network facility and insurer will engage in a single case agreement for the insured.”

The department could not speculate as to why Ochsner refused to proceed with the approved surgery.

‘I have a couple of theories’

It’s possible the terms of the single-case agreement weren’t acceptable to Ochsner. But the Maloshes believe the decision was made because of their relentless advocating for Trevor’s critically-needed care.

“I mean, I have a couple of theories,” Tracy said. “One of them is that they think I’m a Karen crazy b—- and they don’t want to deal with me anymore.”

In January, Trevor’s Molina Healthcare coverage expired and the family switched policies, purchasing one from Ambetter from Magnolia Health on the Mississippi Marketplace. The same 2021 KFF data showing Molina as having a 24.2% denial rate in Mississippi found that Ambetter has a 42.5% denial rate — the highest in the state.

The Maloshes said they chose a plan from Ambetter because their network includes more heart surgeons, including the option to choose one in another state.

Trevor is currently making appointments to consult with surgeons, trying to get a surgery date on the books. It’s now almost the end of February — eight months since his cardiologist first told him he needed a new heart valve — and he’s still waiting. He said he’s worried it’ll take an emergency in order for him to get the care he needs.

“I’ve been told by people that if you show up to the E.R. symptomatic, they have to cover it,” Trevor said. “That’s wild. You’re telling me that I have to wait until I damage my heart to get it fixed when we’ve been working to try to prevent this?”

This story was produced by the Gulf States Newsroom, a collaboration between Mississippi Public Broadcasting, WBHM in Alabama, WWNO and WRKF in Louisiana and NPR.