Image: Shutterstock

Is it really possible for a profit-driven organisation to be sustainable? This existential question may well be keeping leaders awake at night amid pressure from consumers, regulators and investors – and potentially their own conscience. Today’s challenging economic climate is certainly making this question more acute than ever.

Yet, as calls for companies to reduce their negative environmental and social impact grow, many leaders fail to realise the opportunities they bring. Rather than just an added cost, sustainability presents a chance to create value for society, customers and the business. For sure, companies exist to create value – or profits in the eyes of shareholders – which may appear at odds with sustainability. The reality is that leaders can make both responsible choices and profits. But how can they justify it to their stakeholders?

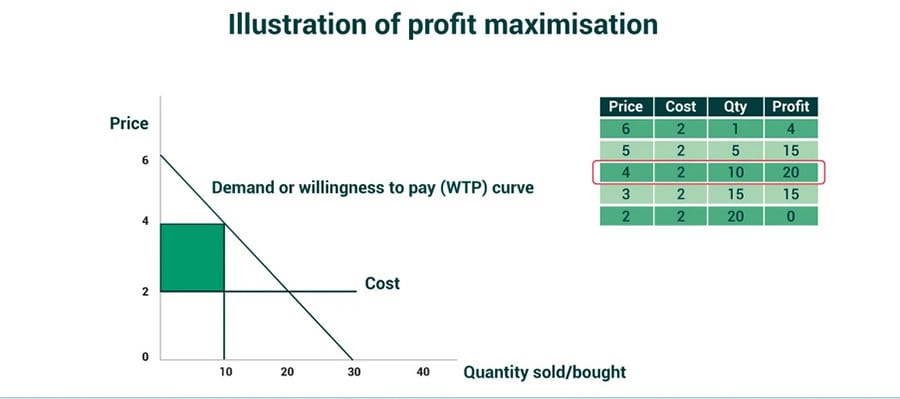

Economic theory offers clues as to how companies can translate sustainability into a “triple win”: a win for society, consumers and companies. The classic price-demand graph (Figure 1) provides the baseline rationale. It represents consumers’ willingness to pay (WTP) for a product or service, with its downward slope depicting the increase in market demand as price decreases. This reflects the fact that buyers often have a very different willingness to pay because of varying preferences, use of the product, or availability (or lack thereof) of alternatives. Profit maximisation, then, involves determining the price and quantity that deliver the highest profit or producer surplus (represented by the rectangle), as shown below.

Figure 1: The classic profit maximisation framework.

Can companies increase producer surplus by offering more sustainable products or services while creating a win for customers and society?

Lowering costs

Sustainability is often associated with higher product costs. If sustainable products do not create more demand (no rightward shift of the demand curve), profits will suffer, which naturally dampens business interest in this pursuit.

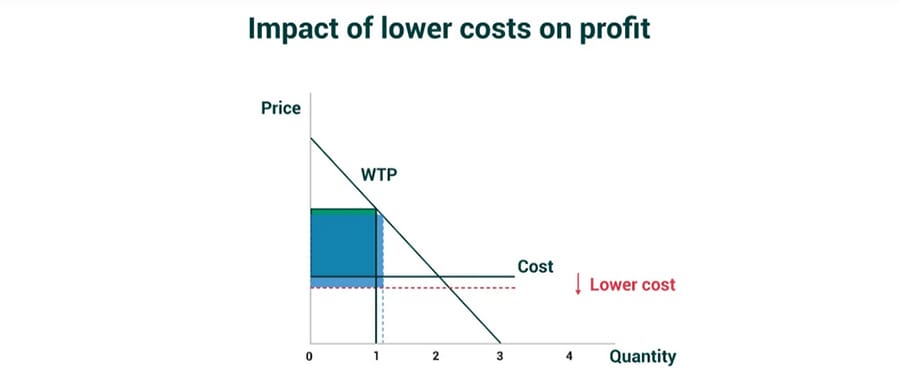

However, if more sustainable versions of existing products can be produced at lower costs, a triple win is within reach. Even if consumers do not consume more, profits would increase, and society would win – and customers could even benefit from lower prices. Figure 2 illustrates this situation.

Figure 2: Cost reduction resulting in higher profits in the absence of demand changes.

Take the example of tires for large commercial vehicles. Large trucking fleets can lower operating costs by using retreaded tires. Although they are more expensive to purchase, the cost per kilometre is lowered by 25 to 40 percent (compared to new “low-cost” tires) once they are retreaded twice or more. Given the cost savings, it makes both business and environmental sense to adopt them, since they also reduce carbon emissions by about 24 percent and the use of natural resources (such as rubber and steel) by about 70 percent, in addition to water and land savings. Even though the demand for trucking services would not increase as a result of using retreaded tires, customers get a more sustainable logistics service, the environment benefits, and the business can expect higher profits per kilometre.

Also read: Ethical dilemmas in business: Balancing profitability, corporate social responsibility

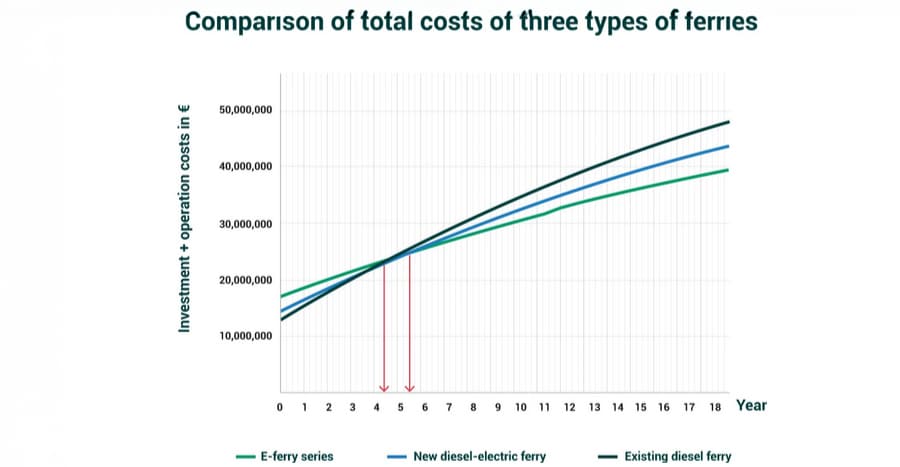

Similarly, in Denmark, the all-electric ferry Ellen was launched in 2019 as a sustainable alternative to diesel-run ferries, which emit about 2,520 tons of carbon dioxide per year. Figure 3 shows the economics of comparable ferries powered by diesel, electric batteries and a combination of the two (hybrid). Although it costs 40 percent less to purchase diesel ferries than electric ones, the operating costs of the electric ferry are 75 percent lower, leading to lower total (or life-cycle) costs after four to six years. Amid the rising cost of carbon dioxide emissions in the European trading system, the business case for e-ferries like Ellen is even more compelling.

However, companies focused on a short time horizon, either due to financial problems or investor pressure, are unlikely to see electric ferries as a “business opportunity”. Instead, they are likely to stay with the legacy product with lower short-term operating costs and will eventually find themselves at a cost disadvantage compared to companies that take a long-term view. Sustainability can be a long-term source of competitive advantage – albeit sometimes at a cost disadvantage in the short term.

Figure 3: The total costs of diesel-powered ferries vs. hybrid ferries vs. electric-powered ferries.

Increasing willingness to pay

Sustainable products and services can require more expensive inputs, such as green steel for cars. However, even if just a segment of the market is willing to pay more for the more sustainable product, this can be sufficient for the company to achieve a triple win: a more sustainable product that some customers enjoy, a benefit to society and higher profits to the company.

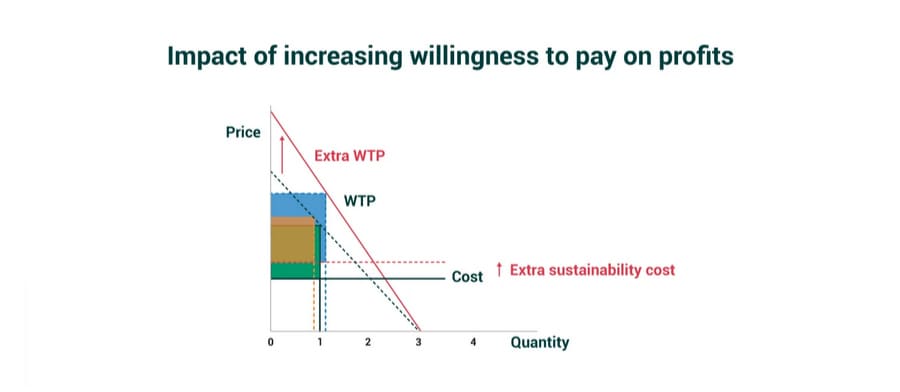

Such a sustainable business opportunity is illustrated in Figure 4. The demand curve moves up along the vertical axis, representing the increase in WTP from a segment of the market, while the demand (represented on the horizontal axis) remains unchanged. When the increase in WTP is significant enough, profits (in blue) can exceed prior profits (in green), making the sustainable innovation economically worthwhile for the business.

Figure 4: Sustainability increasing WTP and business profits.

Figure 4: Sustainability increasing WTP and business profits.

Consider CamelBak water bottles, which are free of the plastic additive bisphenol A (BPA). In 2008, the plastics industry was shaken by stories linking BPA to health concerns ranging from ADHD (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder) to cancer and heart disease. Eastman Chemical responded by launching Tritan, a BPA-free co-polyester that has since been widely used in consumer plastic products, notably those of Eastmans’ customers: bottle manufacturers Nalgene and CamelBak.

Although consumers had to pay a 30 to 40 percent premium due to the higher production costs of Tritan, Eastman Chemical reported that it was “a really great success”. The reason? Its effort to brand, certify and promote awareness of the sustainable plastics together with the bottle makers paid off. The mental association of Tritan with safety and environmental sustainability led to a greater WTP of a segment of end users.

The specialty materials company has since made bold investments in molecular recycling. Made of 50 percent recycled material, Tritan Renew lowers carbon dioxide emissions by 23 percent, while reducing the sustainability premium from 30-40 percent to 10-20 percent.

Willingness to pay for a product can also be increased if it brings overall cost savings. Consider how water utility companies often lose 30-50 percent of water as leaks go undetected or are too costly to fix. Aquarius Spectrum (now under Aliaxis SA) has developed a system of sound sensors to detect leaks in hydrants and pipes. The data is analysed by AI models to identify leaks, significantly reducing the cost of detection and repair for the utility company while also saving water – and the environment. Such a product appeals especially to countries that import water, such as Singapore.

Creating new markets

In the automobile industry, even if some consumers are willing to pay a premium for electric vehicles (EVs) as compared to internal combustion engine cars, intense competition and overcapacity is quickly eroding that premium. Moreover, the higher production cost of EVs puts heavy pressure on EV sellers.

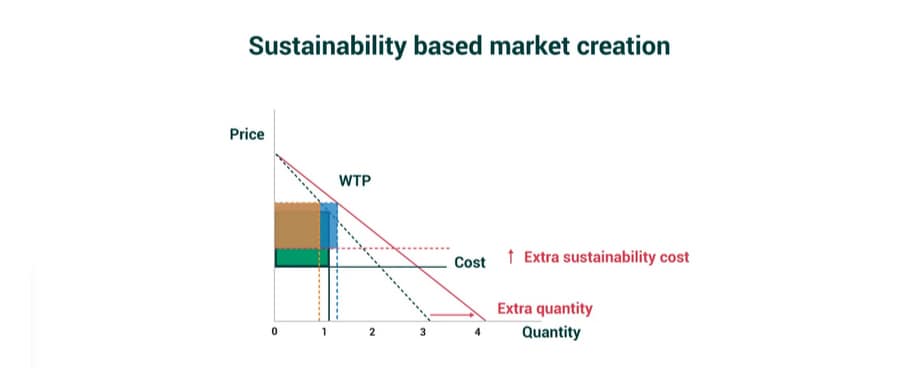

To maintain or even increase profits, companies can extend the size of the market by growing sustainability-driven demand in adjacent segments or creating new markets (as depicted by a shift of demand to the right along the horizontal axis in Figure 5). For EVs, this will likely mean launching less expensive models to appeal to the mass market or specialised vehicles such as small trucks to target price-sensitive companies.

Figure 5: Sustainability-based market creation.

Figure 5: Sustainability-based market creation.

How can we find these new market opportunities? There are several pathways, of which the easiest to identify may be overlooked market segments that tend to be underserved. For example, known for its high-quality tools, Bosch hardly targets the low-end market. However, in exploring circular business models, it began to look into refurbishing returned or broken tools, and soon realised that for refurbished tools, the low-end market is a more feasible target than the mainstream market. For Bosch Power Tools, remanufacturing has become a means to capture new consumers, but also to compete with low-cost, low-quality imports through secondary sales channels.

A second avenue is to look for new customers in adjacent industries, which are often created by shifts in technology, regulation or stakeholder demands. Consider how the construction industry is leveraging lower-carbon, lower-cost construction with engineered wood (also known as “mass timber”) to reach new customer segments. Engineered wood not only reduces the time required for construction, it benefits the environment by acting as an effective carbon sink. Since wood is lighter than the steel and concrete used in conventional construction, costs are lower as only half the support piles and a third of the workers of a typical site are required. Construction companies have embraced this trend, just like how Bouygues built the world’s first aquatic centre with engineered wood for the Paris 2024 Olympics.

Driving sustainability with confidence

Executives can do well and do good at the same time. However, to achieve a triple win for society, consumers and businesses, executives need to have a clear plan and be ready to make difficult choices: which sustainability opportunities to pursue and which to take a pass on.

The economics-based framework discussed here can help them frame and sharpen their plan. Lowering costs, creating willingness to pay and creating new markets are strategies that can offer defensible justifications for sustainable business strategies. A strong business case can help leaders bring shareholders and sceptics on board, while empowering executives to pursue a business sustainability agenda.

This article is based on a piece published in the MIT Sloan Management Review.

[This article is republished courtesy of INSEAD Knowledge, the portal to the latest business insights and views of The Business School of the World. Copyright INSEAD 2024]