My grandmother informed me in regards to the lacking pocket book.

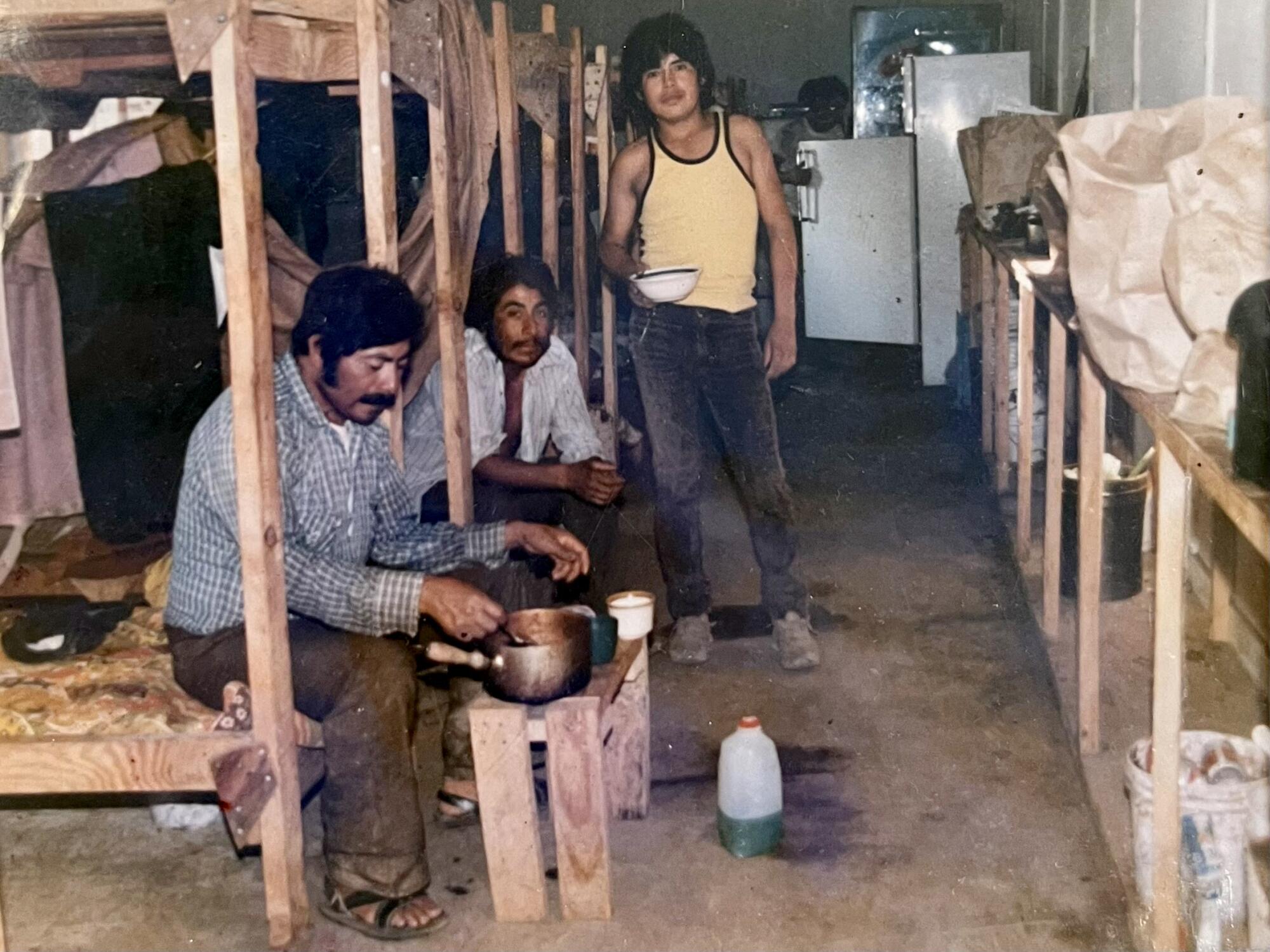

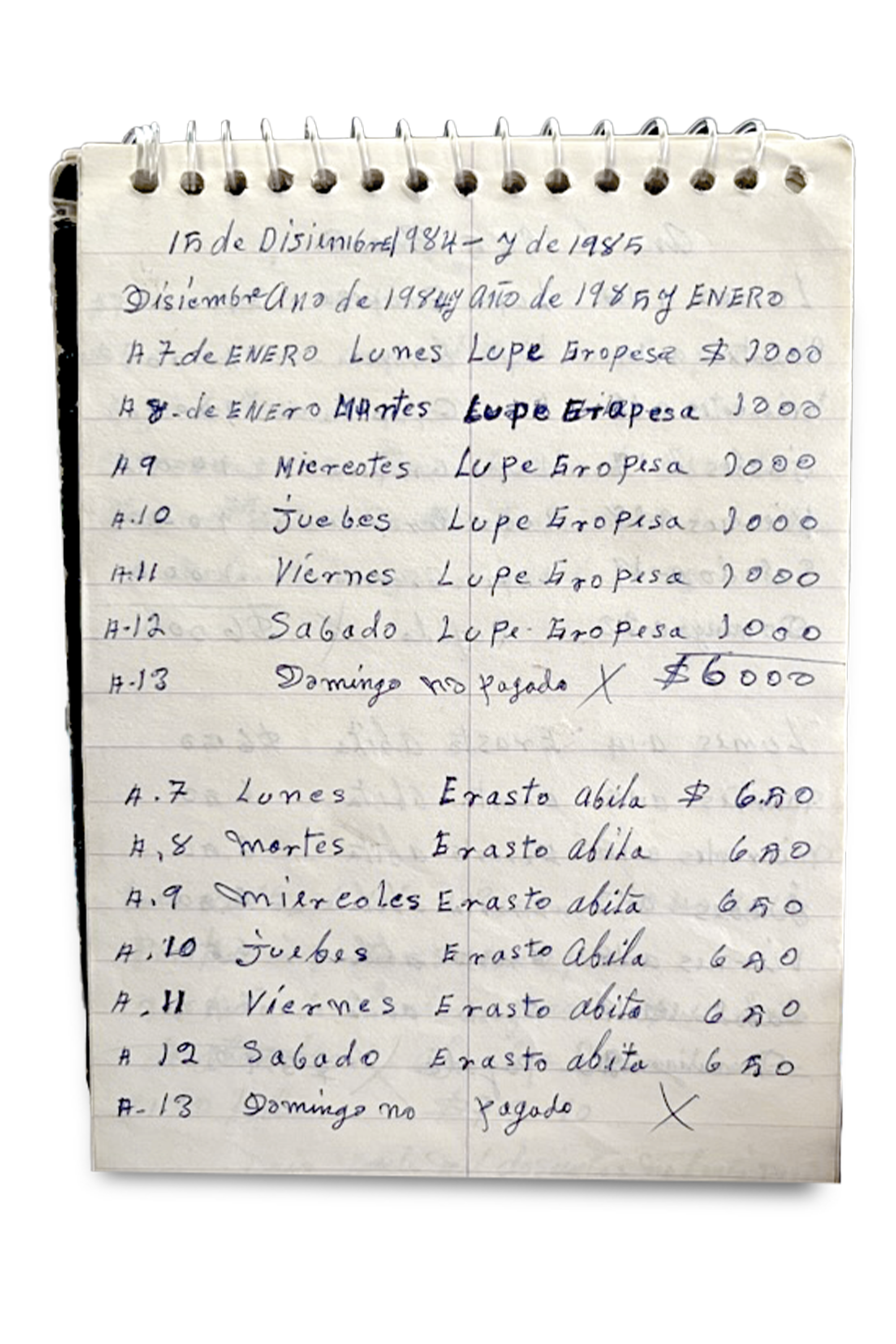

It had a blue cowl, she stated, and was unmarked aside from “cuaderno de trabajo” written within the italicized superscript taught in elementary colleges round Mexico. Stored by my grandfather when he labored on farms and orchards in the USA, the pocket book recorded the place he had labored, how a lot cash he earned and — most necessary — the place that cash went.

The issue, my grandmother stated, was that the “pocket book of labor” in all probability had been destroyed or thrown out. My grandfather, a person of few phrases, didn’t know the place it was both.

However what if that pocket book wasn’t gone?

Pedro Martínez, who meticulously recorded his earnings when he was a farmworker in the USA, relaxes at his house in Huajuapan de León, Mexico.

(Xavier Martinez / For The Occasions)

After graduating from faculty in 2023, I traveled to the Mexican state of Oaxaca to go to family and to report on the consequences of remittances despatched again to Mexico. I used to be unable to seek out previous financial institution information or receipts, however my grandmother talked about the lacking pocket book one night time after dinner.

I knew I needed to see it to be taught extra about my household’s historical past, so I went to the final place Herminia Rodríguez Andrade remembered having seen it: the village the place she and my grandfather, Pedro Martínez, have been born within the Forties and began a household.

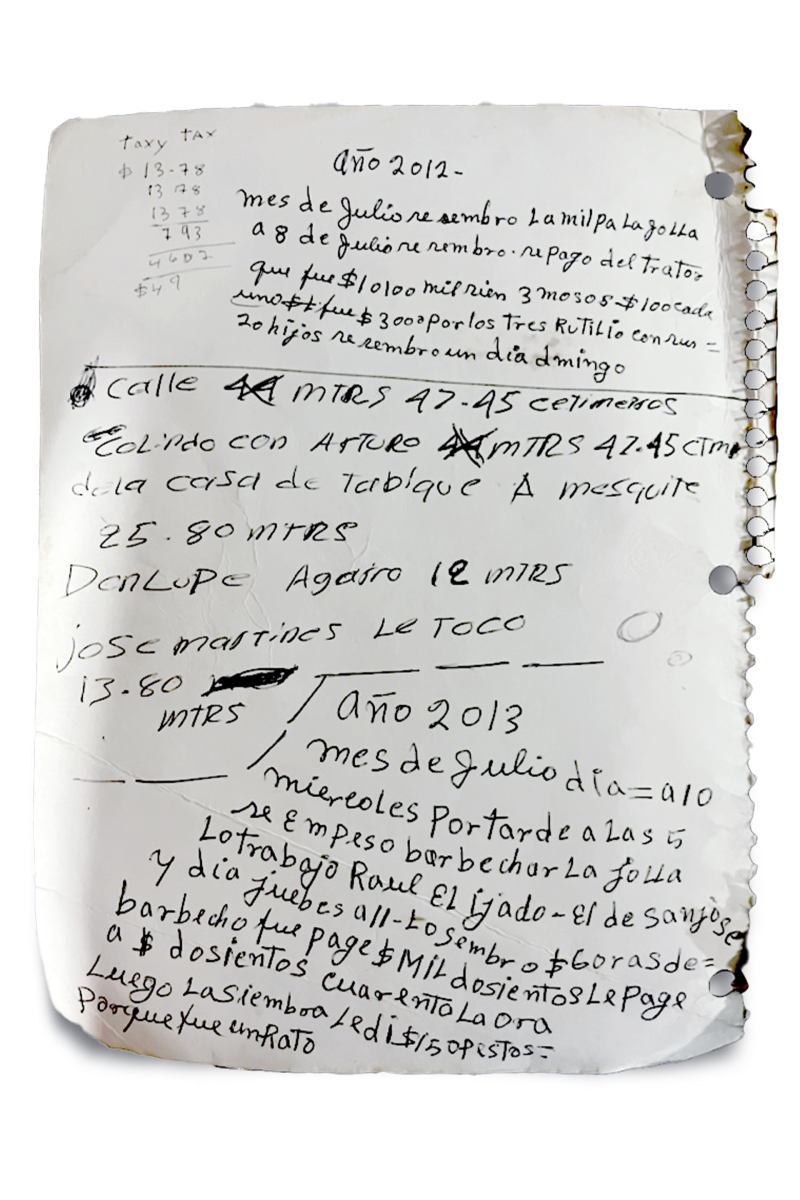

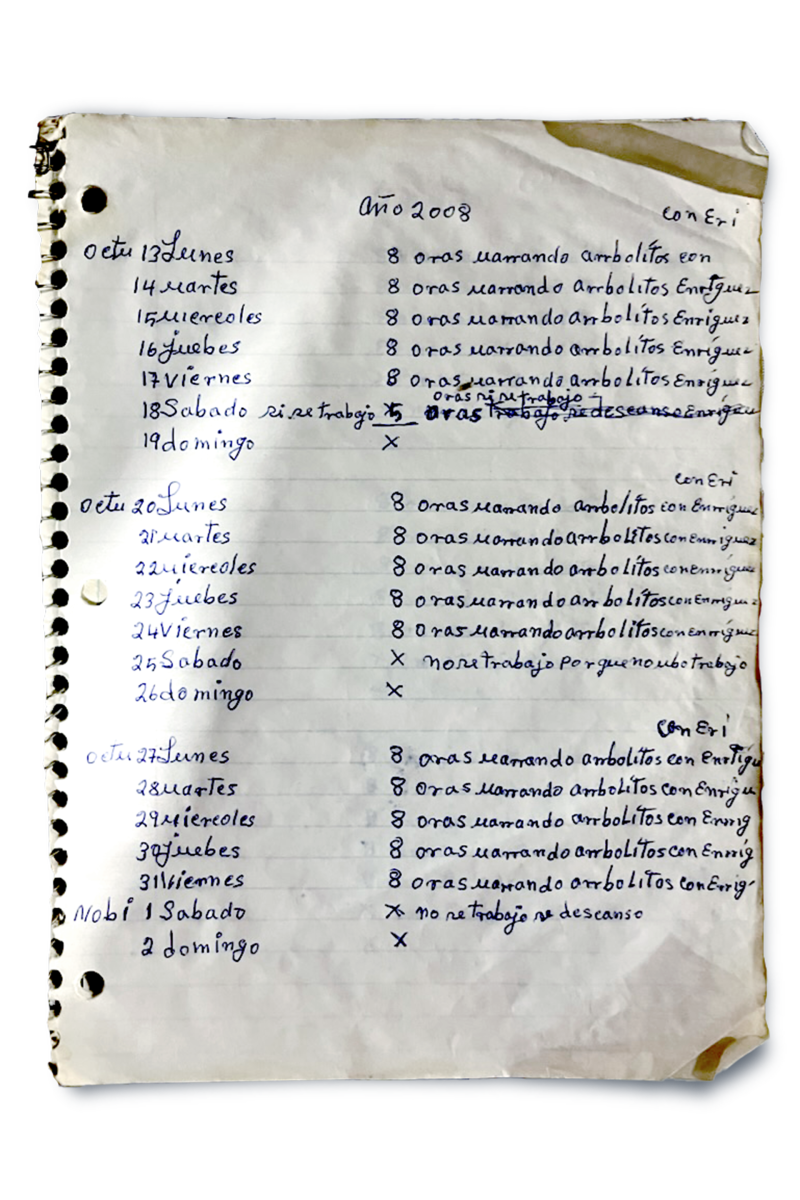

Contained in the two-room adobe home the place the couple and their eight youngsters as soon as lived as subsistence farmers, I sifted via pictures and utility receipts filling a cardboard field that sat subsequent to the one mattress. On the backside, I discovered it: a Mead model spiral-bound pocket book. The entrance cowl almost fell off once I opened it, revealing web page after web page of entries that have been dry, even monotonous.

“October 3, Friday. Eight hours laying wire with Enriquez.”

“November 21. Friday. Eight hours pruning pears. Pruning began right now.”

“December 5, Friday. Eight hours pruning apples with Eri.”

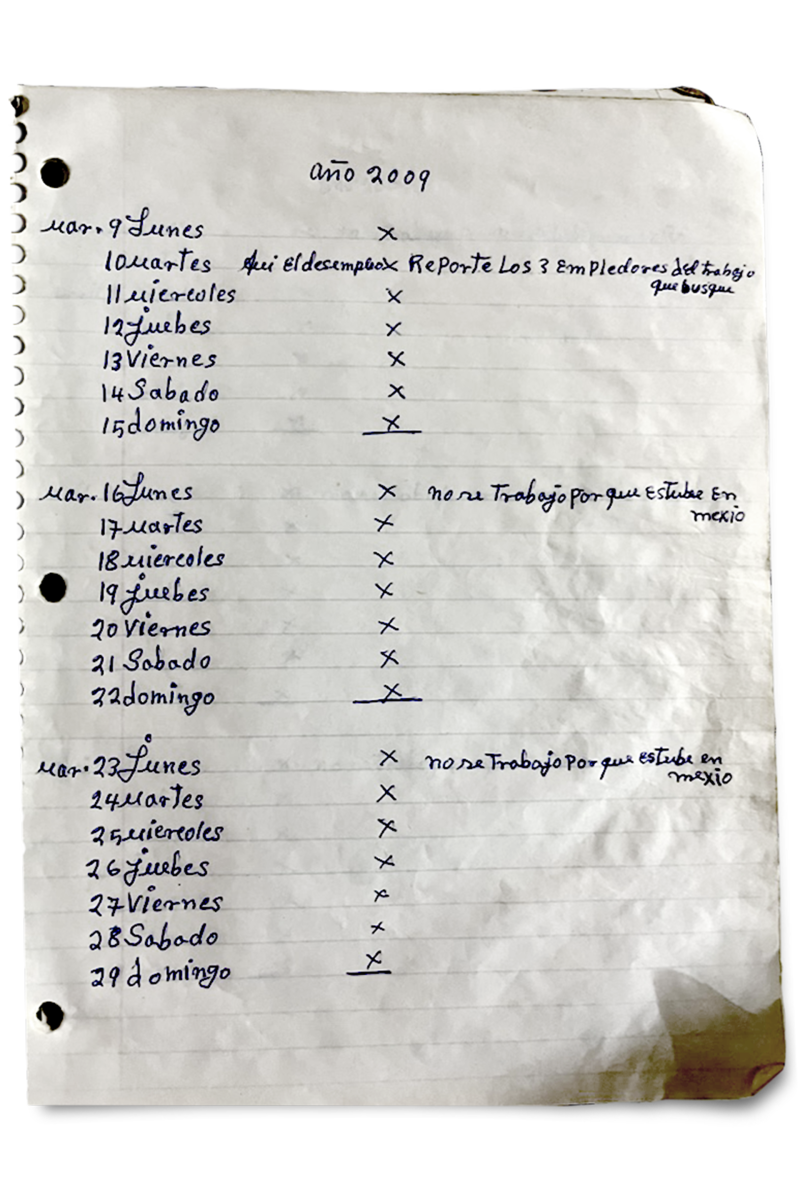

Web page after web page, line by line, I noticed how Pedro lived and labored in 2008 and 2009 within the orchards of central Washington. They traced each job he had and even indicated the times rain reduce a workday quick.

The pocket book was the primary of a couple of dozen ledgers that I’d discover within the adobe home and on the household’s present house in Huajuapan de León, a Oaxacan metropolis of 80,000.

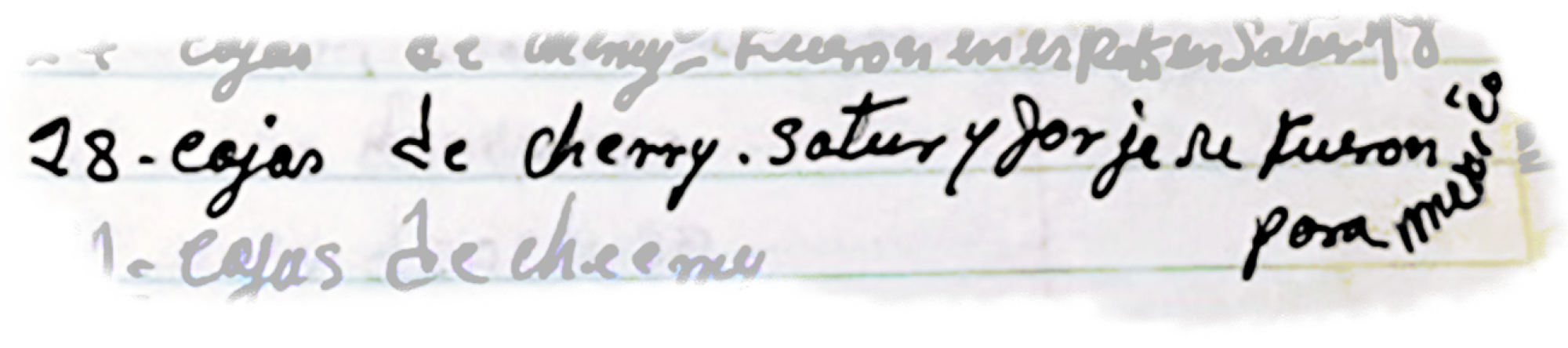

Pedro usually recorded what he earned, as on this entry from 1999: “July 22, Thursday. 18 containers of cherries. $4 per field.”

He additionally recorded the day he made nothing in any respect. Utilizing an X to point zero, on July 26, 1990, Pedro wrote, “X as a result of there was no work.” Some weeks had numerous Xs. The final entry from that 12 months, in November, reads, “On Thursday I left for Mexico at 5 a.m.”

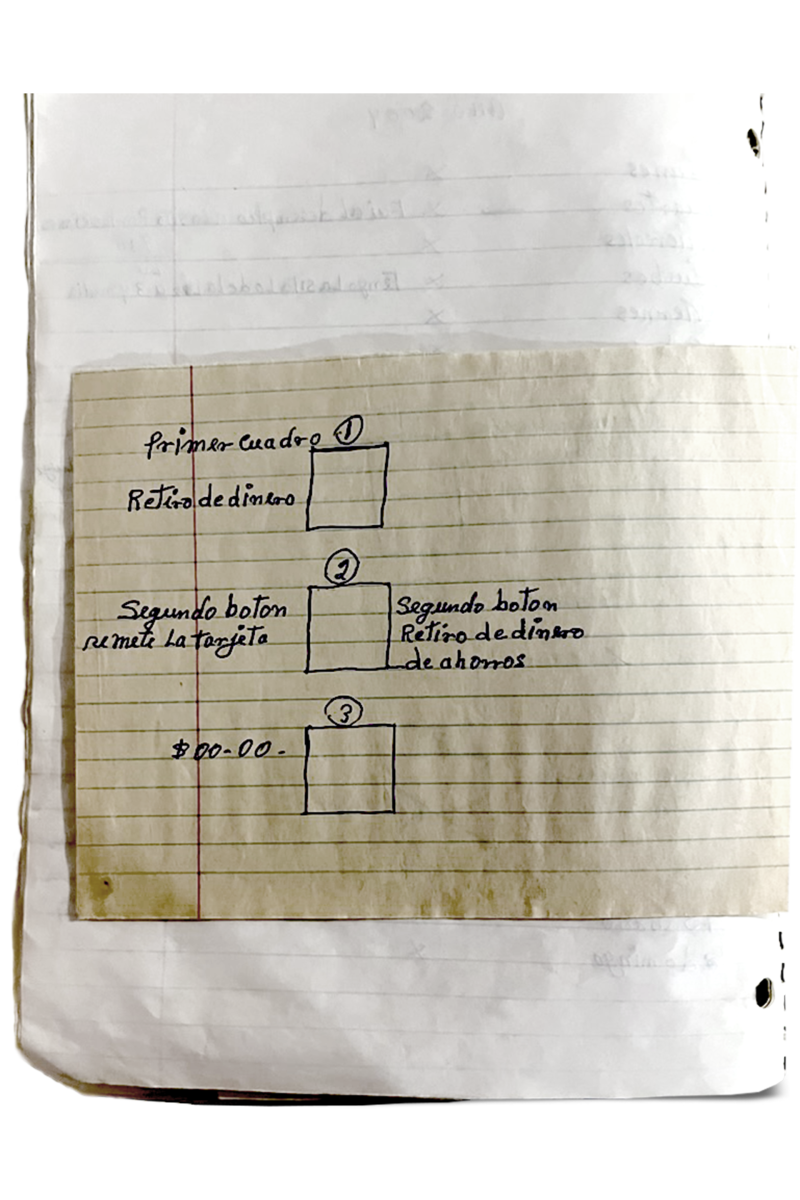

Pedro Martínez practiced English utilizing a pocket book.

With entries from California, Oregon and Washington state, the books have been saved to doc the switch of cash. Now, in a bigger sense, they inform the story of how remittances maintain life in Mexico. Over time, remittances offered a supply of modest generational wealth for my Mexican grandparents, aunts, cousins, nieces and nephews — to the purpose the place my American household not feels the necessity to ship cash, besides in instances of emergency.

The notebooks seize items of Pedro’s life, work and aspirations from 1981 to 2010, when he returned to Mexico for good. They’re far richer than any financial institution information.

Pedro Martínez wrote reminders for himself whereas working as a farmworker in Washington state.

Generally, Pedro drew sketches of the home he deliberate to construct in Huajuapan sometime. It might have six rooms throughout two flooring, with home windows alongside the north facet.

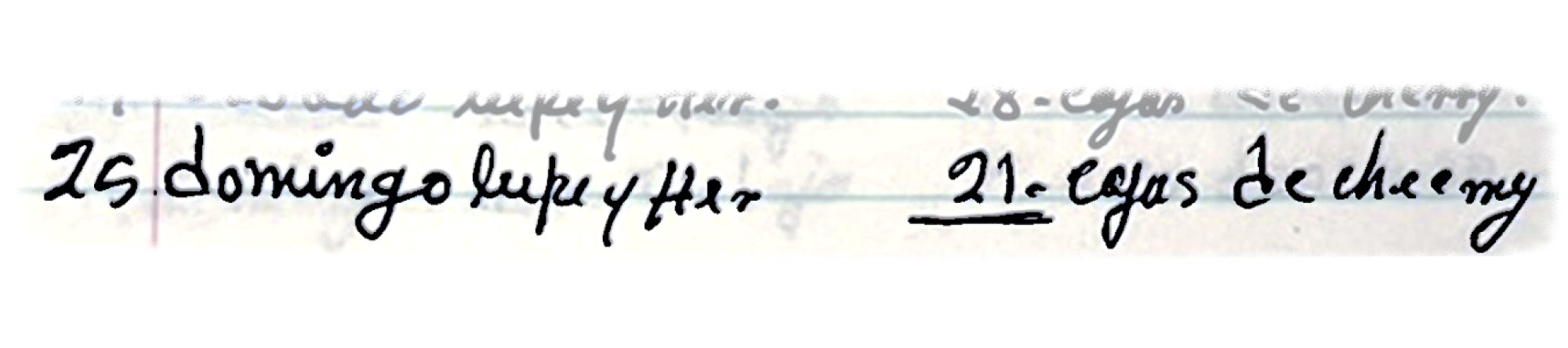

Different instances, he wrote English phrases that he copied from paperwork or discovered from lessons in the USA: “Your worker quantity with Wyckoff Farms is 46450. Please put it on the cardboard.” He additionally wrote down “cherry,” as in “18 cajas de cherry,” as a substitute of the Spanish “cereza.”

Pedro’s notations, although repetitious and even tedious, opened my eyes to his meticulous nature, the best way he considered every greenback as one which couldn’t fall via the cracks.

Cash despatched from the USA performs an outsized position within the economic system of rural Mexican states. In Oaxaca, house to greater than 4 million individuals, residents collectively acquired $2.9 billion in remittances in 2022 — equal to about 12% of the state’s gross home product, in line with the Financial institution of Mexico and authorities figures.

For a lot of recipients of remittances, the funds are used to fill gaps in social companies and to complement a minimal each day wage of 207 pesos, or roughly $10.

Greater than 80% use the transfers for primary wants equivalent to meals and clothes, in line with the financial institution BBVA, whereas fewer than 15% use the cash for schooling. Even fewer use it to purchase land, one other approach during which my household is an exception.

A avenue in Huajuapan de León, within the Mexican state of Oaxaca, to which the Martínez household was in a position to transfer, because of remittances from members of the family working in the USA.

(Xavier Martinez / For The Occasions)

Because the cash is commonly not invested in one thing that might finally generate earnings or promote improvement, like beginning a enterprise, its long-term affect is proscribed, stated Jose Ivan Rodríguez-Sánchez, a analysis scholar at Rice College’s Baker Institute Heart for the USA and Mexico.

Typically, he stated, individuals keep poor.

However in my household, remittances have been used for many years as a pathway to upward mobility.

And all of it started, as with the notebooks, with envelopes at all times bearing three stamps.

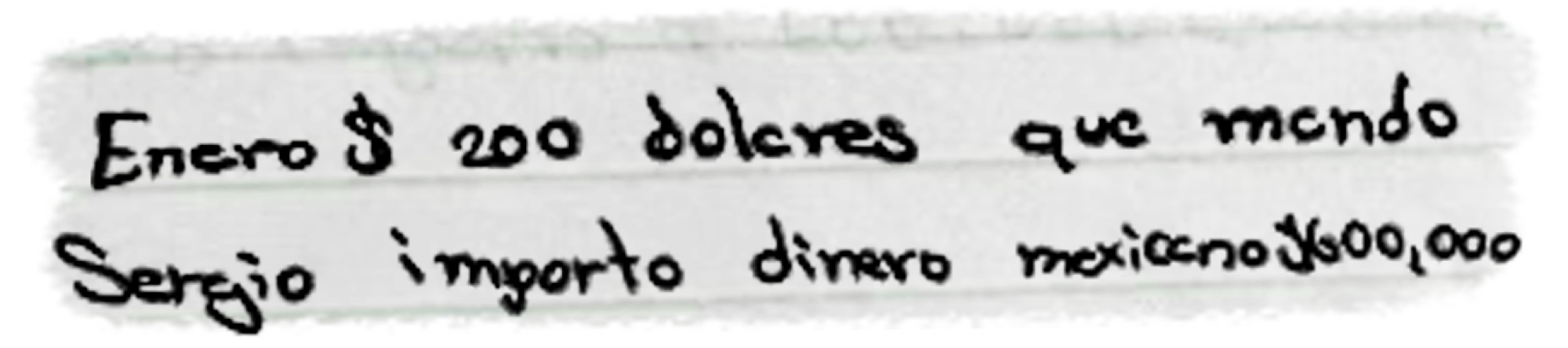

March 12, 1992: Sergio Martinez despatched $200, price 600,000 pesos

Rising up in Wenatchee, a small metropolis in Washington state often called “the Apple Capital of the World,” I knew the significance of remittances from weekly journeys to the tienda mexicana. There, my dad, Sergio, would purchase phone playing cards and name his dad and mom, Pedro and Herminia, to test on the household or affirm they acquired the cash he’d despatched.

Pedro Martínez, who carried out all types of farmwork, prunes a tree in Wenatchee, Wash.

(Martínez household)

I knew that my grandparents grew up the best way most rural Mexicans did within the twentieth century: extraordinarily poor. I knew that poverty led Pedro to observe a gushing stream of laborers from Mexico to chase farmwork within the western U.S. Pedro drifted from San Diego County to Oregon’s Willamette Valley, till he discovered a job he appreciated selecting fruit in arid central Washington.

Column One

A showcase for compelling storytelling from the Los Angeles Occasions.

However there’s a distinction between tales handed down and truths I may be taught as a journalist. It was solely whereas reporting in Huajuapan that I understood the coordination it took to save lots of my family from meals insecurity and the self-discipline it took to keep away from utilizing newfound wealth for pointless purchases.

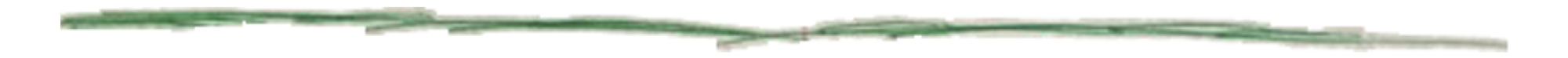

When Pedro first crossed the border with out documentation in 1978 to choose strawberries in Escondido, he lived in a tent on a patch of flat dust close to the farm the place he was working. Intent on saving nearly each greenback of his pay for his return to Oaxaca, he ate wild cactus he harvested from the hills, recalling that they have been “totally different — no, worse — than the cactus at house.”

On his first journey house, Pedro introduced an envelope thick with money. It was the biggest sum of cash the household had ever deposited in a financial institution at one time: $3,600.

Pedro Martínez, left, and two different farmworkers take a break in Wenatchee, Wash., within the Nineteen Eighties.

(Martínez household)

As detailed within the notebooks, that sum was the results of months of modest accumulation: $100 on day, when his wages have been above $4 per field of fruit picked and he may fill greater than a dozen containers; lower than $50 on others, when the dry summer time warmth made it unsafe to proceed work within the afternoon.

After returning to the USA, he started to ship house money in month-to-month envelopes — at all times utilizing three stamps to make sure immediate supply. Herminia and her younger youngsters would decide up the mail and maintain these envelopes as much as the solar, estimating their worth by the silhouette of the payments inside.

In 1985, the couple bought land in Huajuapan, down the road from the central produce market. They constructed a small home the place seven of their youngsters grew up. Every time Pedro returned, he would construct a wall to increase it.

When my father and two of his brothers, Jorge and Saturnino, joined Pedro in Washington within the late Nineteen Eighties and early Nineteen Nineties, with remittances paying the coyotes who bought them throughout the border, they shared a room in a home and didn’t get to maintain a lot of the cash they earned selecting cherries at $4 per seven-gallon crate. They let Pedro allocate a part of their paychecks for his or her residing necessities.

The rest was despatched to Huajuapan, the place their sisters logged every remittance cost in yet one more pocket book for Pedro to evaluate every time he returned for visits.

The ladies purchased new sneakers and ate extra meat, however together with Pedro’s monetary savvy got here a stinginess that prolonged to his household. He refused to pay for any schooling not offered by the federal government.

My grandfather by no means noticed the purpose of utilizing remittances for instructional functions — or for any expense past what he deemed instantly important. This view is frequent amongst many Mexican recipients of remittances, both as a result of their funds are so restricted that extra cash is spent on requirements or as a result of they undervalue schooling as a key to development, in line with Tania Castillo Villegas, who research the consequences of remittances at College of the Isthmus in southern Oaxaca.

By the mid-Nineteen Nineties, my father was in his early 20s and beginning to change into disillusioned with life within the U.S. He had left Huajuapan to keep away from turning into a laborer like his father, and but the one jobs he may discover have been in Wenatchee’s orchards.

Quickly, he stopped taking agricultural jobs, enrolled in English lessons at a group faculty and started to work in eating places. Utilizing the identical methodology of accounting pioneered by their father within the blue notebooks, he and his brothers directed their remittances to go towards their sisters’ schooling.

My dad paid for his sister Nubia’s accounting faculty. Daifa Norma went to a lecturers’ faculty in Mexico Metropolis, and Maribel went to Oaxaca Metropolis for nursing faculty.

July 25, 1999. Lupe and Herminia picked 21 containers of cherries.

Ultimately, Pedro, now 80, settled completely in Huajuapan, his backbone bent by years of climbing ladders with 40-pound luggage of apples on his again. Macular degeneration slowly took over his imaginative and prescient till he was blind. And in July 2023, after coughing up blood for a number of days, he stopped consuming altogether.

His gallbladder may burst at any time, a health care provider warned, and the household needed to determine whether or not Pedro was sturdy sufficient for surgical procedure. Though an operation was dangerous, and the physician gave a 20% chance of a full restoration, the possibilities of survival appeared decrease with out an operation.

The household opted for surgical procedure at a personal hospital in Huajuapan reasonably than on the nearest public hospital in Oaxaca Metropolis, which might have required a bumpy three-hour ambulance journey.

Sergio, my father, arrived a day after the surgical procedure, utilizing the frequent flier factors he had stockpiled for years to safe a last-minute flight from Seattle to Mexico Metropolis. When he arrived in Huajuapan, he was nonetheless not sure of his father’s destiny. On the hospital, he walked into Pedro’s room and located him awake and responsive. The poisonous gallbladder floated in a darkish liquid inside a plastic jar on the bedside desk.

The choice to take Pedro to a personal hospital reasonably than a sponsored public establishment, regardless of the uncertainty of what the ultimate invoice would complete, exemplifies the household’s monetary stability. The hospital invoice exceeded 100,000 pesos (roughly $6,000), an astronomical value for a lot of within the area however a price that the household may afford with contributions from Pedro’s youngsters.

Remittances didn’t pay for Pedro’s doubtlessly lifesaving surgical procedure, at the least indirectly. However they did facilitate the technology of wealth that allowed my father and his siblings to save cash for sudden medical bills. My aunt Maribel, the household nurse who tended to Pedro’s wounds after his surgical procedure, gained the talents she had from the funding of remittances.

Sergio Martínez seems via a household photograph album together with his mom, Herminia Rodríguez Andrade, in Huajuapan de León, Mexico.

(Xavier Martinez / For The Occasions)

It has been years because the household has been involved about having sufficient to eat. Although the household as soon as relied on a area they planted with crops, that area has primarily been allowed to go wild, with corn and cactus rising on their very own, together with avocado and mango bushes. Herminia and Pedro now harvest regardless of the area yields — one thing to complement the kilos of meat and masa which can be bought every week to feed the house’s eight everlasting residents: an assortment of youngsters and grandchildren, and a handful of normal guests.

The household has, in a approach, grown out of its dependence on remittances.

My father, who bought his inexperienced card in 2000, not swimming pools cash or sends set quantities every month. The investments he and his brothers made in schooling have paid dividends for these nonetheless residing in Mexico. Norma is a trainer in Mexico Metropolis, Maribel a nurse in Huajuapan. The third technology, my cousins, are in a position to take non-public English lessons and take part in enrichment packages that my father and his siblings may solely have dreamed of.

Different Mexican households haven’t been as lucky as mine. Generally, accidents or accidents stop migrant staff from making sufficient to ship cash that may accumulate as wealth. In some households, remittance cash is “spent on one thing with none profit for the household,” stated Castillo Villegas.

July 23, 1991: Pedro and Herminia picked 28 containers of cherries. Saturnino and Jorge left for Mexico.

Shortly after my grandfather’s surgical procedure, on a wet night in Huajuapan, my cousin Carmen Méndez Martínez sprinted throughout the concrete driveway to the place the household was seated at a desk.

“¡Me aceptaron en la UNAM!” she stated, panting. She had been accepted to attend the Nationwide Autonomous College of Mexico, the nation’s most prestigious public college.

The adults congratulated her, however their tone was somber. It meant that Carmen can be leaving Huajuapan and, if her aspirations of exploring the world as a health care provider have been fulfilled, she wouldn’t be returning. For Nubia, her mom, it delivered to mild considerations of the household’s closeness. Would her daughter go to? Would she nonetheless really feel an obligation to assist her household?

Carmen is one in all 16 grandchildren beneath the age of 21; the return on my household’s instructional funding is simply starting. One cousin desires to be a dentist, one other desires to affix the U.S. navy. Inevitably, they are going to proceed to unfold out. And to assume these ambitions might be traced again to ledger entries equivalent to “December 5, Friday. Eight hours pruning apples with Eri.”

Three weeks after Carmen was accepted to UNAM, she was on her option to Mexico Metropolis. She stated her goodbyes to her stoic aunts and siblings, tears of their eyes. When she bought to Herminia, her grandmother, Carmen bowed her head for a blessing.

Xavier Martinez is a particular correspondent.