The 28th question of the hardest exam I’d taken since college was a smudged footprint pressed lightly into damp sand. The track possessed four teardrop-shaped toes and a vaguely trapezoidal heel pad; one toe, third from the left, jutted above the others, like a human’s middle finger. I knelt closer, scanning for the telltale pinpricks of claws, and saw none. That suggested feline: Cats, unlike dogs, have retractable claws, and they tend to walk without their nails extended. In my notebook, I wrote, tentatively, BOBCAT.

The hypothetical bobcat had been wandering a sandy floodplain in the California desert, where I found myself taking a wildlife tracking test one April afternoon. The evaluation was administered by Tracker Certification, the North American wing of CyberTracker Conservation, a South African nonprofit that has conducted tracking exams for 30 years. Around me, other students were engaged in their own examinations—peering at a bone-filled lump (great horned owl pellet), inspecting snipped willow stems (woodrat chew), contemplating stick-like prints at the creek’s edge (thirsty scrub jay tracks). The vibe was library-like, studious and hushed, as we attempted to read the land’s open book.

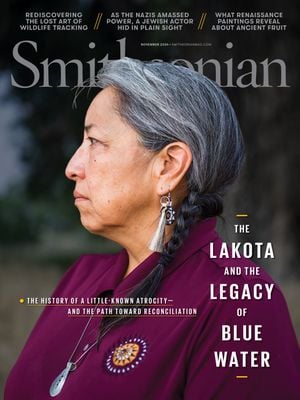

A bobcat footprint—in this case atypical, as the claws, usually retracted, left a mark. Mette Lampcov/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/39/69/3969e7ae-9d29-4976-8c80-ff4a1e78a2ed/nov2024_b18_animaltracking.jpg)

We were participating in an art as ancient as hominids ourselves. Tracking, by allowing humans to more effectively pursue game, drove us into hunting groups, grew our brains, compelled us to adopt language. In his 1995 book The Demon-Haunted World, Carl Sagan posited that tracking shaped our evolution: “Those with a scientific bent, those able patiently to observe … acquire more food … they and their hereditary lines prosper,” he wrote. Tracking helped to transform a small, furtive ape into a global force.

No longer does our survival depend upon our ability to stalk a springbok. Homo technologicus is more attuned to screens than to scats; the trails we follow are paved highways rather than pawprints. Even the field of wildlife biology has become reliant on technology. Scientists use satellite collars to monitor caribou from their desks; drones hover over penguins in Antarctica; motion-activated cameras snap photos of every creature that crosses their infrared beams. Today a herpetologist can identify each frog, toad and salamander in a creek by sifting through snippets of DNA in the merest vial of water. Crouching over skunk prints and jackrabbit pellets feels analog by contrast, even anachronistic.

Yet old-school tracking—a cheap, noninvasive method capable of providing astonishing quantities of data—is experiencing a revival. These days biologists are examining tracks for many purposes, from forestalling wildlife conflicts to averting roadkill. In Wisconsin, trackers are following wolves to prevent them from running afoul of livestock and humans; in Washington State, they’re observing faunal footprints returning to river valleys after dam removal. Biologists have trailed the antelope-like saola through Southeast Asia’s mountains in hopes of capturing and breeding it, and stalked lynx and wolverines across Montana to understand their abundance and distribution. Many tracking-based studies make use of data collected by volunteers, who, with training, can follow animals as skillfully as academic scientists. “It can be this very accessible, democratic way of gaining information,” David Moskowitz, a naturalist, photographer and expert tracker, told me.

In the past two decades, Tracker Certification has conducted nearly 700 formal field evaluations during which it accredited more than 2,300 individual students. They make up an eclectic array of people. The participants in my workshop included photographers, teachers and hunters; there were biologists, yes, but also chemical engineers and real estate brokers who spent their weekends volunteering on mammal surveys. At the morning’s outset, we’d gathered in a sandy wash and, squinting into the rising sun, explained our sundry motivations. One student said he longed to “read the little letters that the world is writing you”; another declared that he “didn’t want to feel like a tourist” in the natural world. “You’re all helping to revive real field skills and natural history skills across the planet, in a way that is desperately needed,” Casey McFarland, Tracker Certification’s ebullient executive director, had declared. Then he’d released us—to scrutinize spoor, to pore over prints, to track.

For nearly the entirety of human existence, our species regularly performed feats of tracking that, from our modern vantage, resemble magic. So Elizabeth Marshall Thomas learned one day in the 1950s, when she set out with three Ju/’hoansi, hunter-gatherers in Namibia’s Kalahari Desert, on the trail of a hyena. Thomas’ parents, ethnographers and adventurers, had moved their family to the Kalahari when their daughter was 19, and the Ju/’hoansi’s practical brilliance instantly awed Thomas. The Ju/’hoansi shot wildebeest and other game with poisoned arrowheads, then tailed their dying quarry for many miles. This required not only distinguishing tracks at the species level, but also recognizing individual animals: If a herd of kudus split up into several bands, the Ju/’hoansi had to remain on the trail of the particular kudu they’d shot. It was a skill “that must be seen to be appreciated, especially because none of the tracks are clear footprints,” wrote Thomas, in her 2006 book The Old Way. “Mostly they are dents in the sand among many other scuffed dents made by the other kudus.”

In the 1950s, Elizabeth Marshall Thomas documented the tracking skills of the Ju/’hoansi, hunter-gatherers in southern Africa’s Kalahari Desert. Peabody Museum of Archaeology & Ethnology/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/10/d6/10d66084-2608-4244-919f-dfe6393d9610/nov2024_b24_animaltracking.jpg)

Yet even Thomas couldn’t believe how her companions followed the hyena across an expanse of bare rock. “They were not simply following the line of travel, because out on the rock, the route of the hyena made a curve of about one hundred degrees,” she wrote. There were no footprints, no drops of blood, no bent grasses. Still, when the party reached the sand beyond the plateau, there resumed the hyena’s tracks, exactly where the men expected. “How they did it I have no idea.”

North America’s Indigenous peoples, of course, shared an equal intimacy with tracks. “It’s culture for me—it’s in my religion and my people’s history,” Ahíga Snyder, a Diné, or Navajo, wildlife researcher who co-runs Pathways for Wildlife, a research group in California, told me. Tracks featured prominently in the Diné animal stories that Snyder’s grandfather told him. Take Black Bear, whose front paws have straight, evenly sized toes that can sometimes make it hard to tell a right foot track from a left—because, per Diné legend, the bear woke up late on the day that the Great Spirit assigned each animal its tracks and, in his haste, slipped his moccasins onto the wrong feet. Or consider Deer, whose hooves formed an arrow said to point toward prosperity, appropriate for such an important game animal. Understand tracks, Snyder said, and “the whole world opens up differently.”

Scientists held tracking in high esteem well into the 20th century. In a 1936 paper titled “Following Fox Trails,” the biologist Adolph Murie described spending months shadowing red foxes in Michigan. (Sifting through their droppings, Murie reported “many rabbit bones and pieces of fur, the skull and a piece of the hide of a muskrat, the rear half of a fox squirrel, the posterior part of a skull, scapula, and femur of a lamb, part of an adult deer sternum, and some blue jay feathers.”) As technology improved, however, biologists adopted tools like satellite collars and motion-activated cameras, which allowed researchers to glean vital data across vast areas with less labor. Tracking fell out of favor.

In some ways, tracking’s revival began in the 1980s, when a South African physics student named Louis Liebenberg abandoned his studies, bought a Land Cruiser and drove into the Kalahari Desert to commune with the San, a group of hunter-gatherers that includes the Ju/’hoansi. Liebenberg had always loved to track; while serving in the military, he’d occasionally abandon his post to sketch animal footprints. Liebenberg spent years with the San, watching them track and nearly dying of heatstroke during an antelope hunt himself. Tracking was not antithetical to science, he concluded. It was science. Following animals inherently required observation and inference; what was pursuing a trail if not testing a hypothesis? Just as physicists deduced the existence of subatomic particles from the movements of visible matter, San hunters reconstructed the behaviors of invisible animals from tracks. It was conceivable, Liebenberg wrote, that “the creative scientific imagination had its origin in the evolution of the art of tracking.”

That art, however, was at risk of disappearing. Many San neither wrote nor read; meanwhile, ranch fences across the Kalahari had curtailed wildlife migrations and threatened hunter-gatherer life ways. Around campfires in the early 1990s, Liebenberg and a San named !Nate began to discuss how to simultaneously preserve traditional knowledge and provide Indigenous trackers a credential they could use to secure jobs as ecotourism guides and park rangers. In 1994, Liebenberg began conducting training workshops and accreditation tests for San trackers. He and others also developed an elaborate pictorial system, first operated on a PalmPilot and later on smartphones, that allowed trackers to record and share their observations. They called the system, released in 1996, CyberTracker.

Together, the CyberTracker software and Liebenberg’s certification process proved their worth. Non-literate San co-authored peer-reviewed papers on topics such as black rhino behavior and found work defending animals from poachers. In 2002, hoping to expand his system to the United States, Liebenberg attended a wolf tracking workshop in Idaho, where he met , a young wildlife biologist who’d cut his teeth studying mountain lions in Wyoming. Elbroch spent portions of the next three years in the Kalahari, trailing animals from lions to porcupines with Liebenberg and his San colleagues and, between trips, applying his newfound knowledge to black bear and cougar tracks at home near Santa Barbara. Elbroch eventually aced his exams in the Kalahari and Kruger National Park, and he and Liebenberg set about importing CyberTracker’s protocols to the United States. In 2004, they conducted an evaluation in the California desert and, the next year, Elbroch led one for staff at the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. “At first they were confused and frustrated: ‘What the heck are we looking at?’” Elbroch recalled. “By midday, everyone was having the time of their lives.” CyberTracker’s standards had been developed on zebras and African lions; they would be honed on mule deer and cougar.

These days Elbroch lives on the Olympic Peninsula, the wedge of temperate rainforest that juts from western Washington like a thumb. One autumn morning, I set off into the Olympic woods with Elbroch and Kim Sager-Fradkin, a wildlife program manager with the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe, to reconstruct a day in the life of a mountain lion. The cat was a 2-year-old male, named Orion, whom scientists had outfitted with a satellite collar under the auspices of a long-term study called the Olympic Cougar Project. Mountain lions are generally peripatetic, but, according to Orion’s collar, he’d recently lingered in one area for more than a day—a hint that he’d made a kill and hunkered down to eat. Now Elbroch hoped to find Orion’s meal and piece together the circumstances surrounding his feast.

The three of us tramped through stands of alder and shafts of sunlight. “Bobcat scrape,” said Elbroch, who sported a gray-flecked beard and a T-shirt bearing his own detailed illustration of a cougar skull. He nodded to a barely perceptible patch where a cat had cleared the leaf litter and urinated to mark its territory. Moments later, we came upon another, larger scrape. “Notice the size difference? This is probably our boy.” He picked up a broken fern frond, browned and curled at its edges. “Following animals is all about color and pattern,” he whispered.

Beyond the scrape ran a faint swath of exposed ground where Orion had hauled his prize. “Whatever’s at the end of the rainbow, this is where it starts.” He turned to me. “All right, now you’re loose. Lead on.”

Mark Elbroch, a wildlife biologist and decorated tracker, helped bring Tracker Certification’s standards from South Africa to North America. His guidebooks are renowned within the field. David Moskowitz/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/7e/03/7e035b97-cefd-4778-bcf3-2e3c7c62e72e/nov2024_b22_animaltracking.jpg)

I blanched. Mark Elbroch asking me to trail a cougar was like Jimmy Page suggesting I play a few chords. “They almost always drag downhill,” he said. I stumbled down a steep slope, clambering over moss-garbed deadfall in pursuit of an apparent dragline. At the bottom, I paused to get my bearings. Nary a scrape to be seen; the ferns looked as fresh as though they’d sprouted that morning.

“We’re up here,” Elbroch called from a ridge.

“I thought they dragged downhill,” I complained. He smiled and shrugged.

I rejoined Elbroch and Sager-Fradkin as they traipsed along, pointing out what trackers call “sign,” or any animal trace besides a footprint: the exposed root where the carcass had rubbed off moss, the matted earth where Orion had curled up to digest. Plate-sized globs of bear scat lay everywhere, and the bruins’ beds cratered the forest floor. “Bears are big, lumbering beasts that leave a lot of sign,” Sager-Fradkin said. “They’re not delicate and neat like cougars are.”

She and Elbroch were looking for the cache, the trove where Orion had hidden his leftovers. Elbroch paused before an unassuming smudge of dirt, perhaps bloodstained, and began to root with a stick. The odor of rotting meat wafted up. He plunged his hand into the soil and, with the flourish of a magician revealing the ace of spades, held up the skull of a mountain beaver—an odd rodent, unrelated to true beavers, whose burrows pockmarked the hillsides. A few inches deeper and he unearthed an off-white fragment of zygomatic arch, a bone that once resided in the head of a small deer. A narrative cohered: Orion had killed a fawn, lugged it here to consume and stash, and, between helpings, captured a passing mountain beaver, as though nabbing a bacon-wrapped scallop off an hors d’oeuvres tray. Before Orion could disinter his fawn, though, he’d been run off by a bear. There was no way to confirm the story’s veracity, but it felt entirely plausible.

This exercise wasn’t only an enthralling party trick—it also had profound value for the Olympic Cougar Project. While satellite collars could tell Elbroch and Sager-Fradkin where cougars approached I-5 and other highways, thus guiding the location of future wildlife passages, only tracking could reveal what they ate. Figuring out how many deer and elk the peninsula’s cougars killed, for example, could help tribes determine hunting quotas, thus keeping game on the landscape for felines and Native people alike. Studying the dietary preferences of males like Orion, who often run afoul of humans while searching for territories, is especially vital. “The naive ones don’t really know where to go and how to avoid people,” Sager-Fradkin said. Instead, they occasionally develop the unfortunate habits of attacking goats, calves and other livestock, and following small prey like raccoons into neighborhoods until they learn to hunt deer. Understanding the diets of these rambunctious cats may help prevent conflicts between the carnivores and people, and protect the species upon which dispersing cougars rely.

“We’re redefining these animals to hopefully learn how to live with them,” Elbroch said as we crouched in the duff, examining bone shards. There are still questions that can only be answered by digging in the dirt.

After my experience trailing Orion, I resolved to try tracking myself. I bought one of Elbroch’s guidebooks and began canvassing my home landscape in Colorado. I marveled at a twisted mink scat packed with a snake’s tiny skeleton and the pointillist artwork inscribed in aspen bark by a black bear’s claws. Yet my callowness left me unfulfilled. Consulting Elbroch’s books might lead me to believe that a pawprint had been left by a red fox rather than a gray, but I couldn’t be certain. I craved validation.

That was how I ended up in California, scrutinizing bobcat prints in hopes of passing a tracking test. The exam’s format was simple, its content challenging. Beforehand, our evaluators—McFarland, Tracker Certification’s executive director, and Marcus Reynerson, a senior instructor at a wilderness school—had scoured the desert for animal tracks, scat, gnawed twigs and other oddities. They planted an orange flag at each impression; our charge was to figure out what was responsible for the various marks. (Some questions were complex multiparters that required us to identify not only what animal had left a given track, but also its pace and the responsible foot: left front, right hind and so on.) Once we’d devised our answers—which, in my case, could charitably be described as semi-educated guesses—we whispered them, or showed them in writing, to clipboard-wielding assistants.

Casey McFarland, Tracker Certification’s executive director, left, and Marcus Reynerson, a wilderness school instructor, served as evaluators during a recent exam. Mette Lampcov/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/7f/0d/7f0da6c4-ec51-4240-aab1-bb6f390b9b6e/nov2024_b16_animaltracking.jpg)

From a distance, the desert appeared a barren expanse of rock and sand, but up close it throbbed with life. We were asked to explain the provenance of a bone shard (a coyote’s scapula) and a silk-lined hole (a tarantula’s burrow) and a white crystalline splatter (wonderfully, calcium from the urine of a desert cottontail). Most of all, we had to know tracks. A raven’s inner toe was tucked close to its middle, whereas a jay’s toes were clustered together. Two long paddle-shaped marks, punctuated by a pair of small circles, were the hind and front feet of a resting jackrabbit.

Each time we finished answering a batch of questions, we gathered to debrief. I’d been dreading this part, which promised to expose my ignorance, but I needn’t have worried: The vibe was less oral examination and more Socratic dialogue. How do you tell a domestic dog’s claws from a coyote’s? (Among other differences, dogs leave blunter marks, since their nails are clipped or filed down on pavement.) How do we know this turd came from a toad? (It’s gleaming with insect exoskeletons.) McFarland and Reynerson, good-natured and nonjudgmental, greeted even incorrect answers with an exclamation of “Fantastic!” Wrongness was an opportunity to learn.

This point was reinforced when we were asked to identify the source of chew marks on a prickly pear. “I thought it was a mule deer,” one student said. (I’d guessed bighorn sheep, which often eat cactus in the desert.) “Excellent!” McFarland enthused. Then he pointed out what was missing from the scene: the spines of the cactus. A deer or sheep would have nibbled the prickly pear’s flesh around the needles, which would then have fallen to the ground; their absence suggested that some creature had carried them off. This, then, was the toothwork of a woodrat, which had borne away the spines to armor its nest. “They’re getting a food source, but they’re also getting protective equipment,” McFarland said. Even a diminutive rodent wrote upon the earth.

Sometimes, as we perused tracks and sign, I was appalled by my ignorance: How could I have confused that rabbit pellet for a squirrel’s? Other times I felt insightful, as when I picked out the shuffle of a quail from a welter of scuffs. Most of all I appreciated the rarity of this experience: to hunch, for long and silent minutes, over a scratch or dropping. I felt that I was back in an English classroom, slowly digesting and interpreting a complex text. “This is the first alphabet that we as a human species had to be able to read,” Sarah Spaeth, an evaluation assistant, told me during a quiet moment.

Tracking relies on more than identifying footprints. Experts interpret all manner of evidence an animal leaves behind, known collectively as “sign.” Mammal sign can include scat, burrows and bedding areas. Birds might discard feathers or regurgitate pellets—undigested food that can contain bones, fur, seeds and other substances. From left: a common raven pellet; an illustration of the bird; Mette Lampcov; Roger Hall / Scientific Illustration/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/84/04/84049fd8-9f13-4b6f-8745-1ed7f3bfb329/animal1.jpg)

Spaeth, who was visiting from western Washington, is at the vanguard of the tracking revolution. The director of conservation and strategic partnerships for the Jefferson Land Trust, Spaeth had begun tracking more than a decade earlier, after she’d attended a workshop and gotten hooked. (During one early evaluation, she’d correctly identified the pockmark produced by a male elk’s urine stream.) She found tracking to be invaluable in land conservation, since it helped her confirm that wildlife was indeed inhabiting and moving between the parcels that her organization protected. “It’s such an incredible tool,” she said.

She is hardly the only researcher to rediscover tracking’s worth. For the past decade, McFarland told me, Tracker Certification’s goal had been to train and certify as many trackers as possible. Its recent growth has been exponential: In 2021, the group conducted 46 evaluations in North America. In 2023, it ran 92. Now the organization was preparing for its next phase, deploying trackers in the realms of wildlife research and conservation, and exposing academics and government agencies to tracking’s validity. McFarland himself was leading that endeavor: He would soon spend ten days trailing bears with biologists from the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, in hopes of quantifying how many fawns the ursids were devouring. “There are these cool areas where skilled trackers in combination with modern technology could produce some awesome results,” he said.

For tracking to truly influence wildlife biology, however, it will have to overcome reputational challenges. Tracking, after all, is a methodology reliant upon human interpretation—and humans are fallible. One 2009 study in the Journal of Wildlife Management found that Texas biologists surveying otters frequently mistook raccoon, opossum and even house cat tracks for otter prints. As the authors cautioned, “issues with observer reliability … are potentially widespread.”

A Virginia opossum and its tracks—Question 51 of a recent exam. Elbroch’s field manual shows the front and hind footprints. Mette Lampcov; Roger Hall / Scientific Illustration/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/de/df/dedf95cf-1bf7-4499-9995-9710f8433be6/animal2.jpg)

Granted, technology itself isn’t incontrovertible: In a study published in the Journal of Mammalogy in 2018, Elbroch found that tracking produced more reliable estimates of mountain lion kill rates than computer models based on satellite data. Yet concerns about tracking’s accuracy still dog the scientists who employ it. “On nearly every paper that I’ve submitted where I’ve used tracking, I’ve had the reviewer criticize the use of tracking and be like, ‘That’s not really good enough,’” Sage Raymond, a Canadian wildlife biologist, told me.

Raymond is among a burgeoning class of scientists trying to take tracking mainstream. In 2021, she moved to Edmonton, Alberta, to study urban-adapted coyotes, and realized the snowbound woods were rife with “little coyote highways” of pawprints and scat. Over three years, she followed more than 300 miles of coyote trails—up ridges and down ravines, through thickets and under bushes. (“I shredded some coats,” she recalled.) The canids’ tracks often led Raymond to their dens, which, she said, are “embedded in the anthropogenic matrix”: in other words, near humans and our infrastructure. “People have no idea that there’s a coyote with a full-on den and eight pups just 20 meters from their property line,” Raymond said.

Although coyotes tend to be shy, polite neighbors, they occasionally approach humans and pets and can attack when their pups are threatened, especially when they are habituated to human food—conflicts that Raymond’s research could help alleviate. Edmonton’s coyotes, Raymond has found, excavate their dens on hillslopes covered in thick brush. If a likely den site occurs near, say, a school, “maybe just thin some of that vegetation, and that’s probably enough to disincentivize coyotes from having a den.” Tracking wild creatures helps us coexist with them.

Students prepare for a field exam. The nonprofit Tracker Certification North America has evaluated more than 3,000 people since 2004; roughly 2,300 passed. Mette Lampcov/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/51/e2/51e29b75-d59f-4c19-813c-7185ee540846/nov2024_b21_animaltracking.jpg)

Tanya Diamond, Ahíga Snyder’s partner at the California-based research group Pathways for Wildlife, is likewise using tracking to smooth human-animal relations. Diamond and Snyder specialize in the field of habitat connectivity—figuring out how animals navigate landscapes so that environmental groups and agencies can protect those corridors. For Pathways for Wildlife, the first step is searching for deer, coyote, badger and mountain lion sign, to determine faunal travel routes; they then install motion-activated cameras along those thoroughfares to observe animal behavior. In 2022, Diamond and Snyder found the tracks of migrating mule deer intersecting with Highway 395 near Lake Tahoe, set up a camera, and captured heartbreaking video of a deer getting pulverized by a car—a tragedy, yes, but one that helped convince the state to fund a wildlife overpass to usher the herd across the asphalt. Thanks to tracking, Diamond said, “that deer’s life is not in vain.”

Ultimately, tracking doesn’t clash with camera traps and other technology—it harmonizes with them. Few researchers have proved that point more clearly than Zoë Jewell, a Duke-affiliated wildlife biologist and co-founder of the group WildTrack. Jewell’s passion for tracking originated in the 1990s, while studying black rhinos in Zimbabwe. Her research entailed working with rhinos that had been sedated and fitted with radio collars, a process so stressful that some females slowed their reproduction or miscarried; meanwhile, local trackers mocked her fancy receivers. “All you need to do is look at the ground,” they told her. She learned to track and, over the course of a decade, developed a protocol for photographing the footprints of rhinos and other wildlife and differentiating the prints by age and sex. In a 2001 study in the Journal of Zoology, she and colleagues showed that, by measuring and comparing the precise dimensions of footprints, they could identify individual rhinos with up to 95 percent accuracy. “If you work with trackers and interpret their knowledge, there’s a huge amount of benefit to be had,” Jewell told me.

Over time, Jewell applied her footprint measurement technique to other species, from cheetahs to otters to mice. She also began to work with students at the University of California, Berkeley, to develop a machine-learning program that could identify footprint photos. Although Jewell initially doubted that artificial intelligence was up to the task, WildTrack’s A.I. program can today identify 20 species with near-perfect accuracy, and individual animals of nine of those species around 87 percent of the time. And the program is only growing more powerful as volunteer scientists, from hikers in Colorado to the San in the Kalahari, submit images of footprints to WildTrack’s database using a public app. Today A.I.-based tracking is being used from South Africa, where biologists are monitoring mouse populations, to Nepal, where researchers are helping herders figure out precisely which tigers are killing their livestock.

Terry Hunefeld, a professional tracker, analyzes the corpse of a Botta’s pocket gopher. The burrowing rodents leave telltale fan-shaped mounds of soil at their tunnel entrances. Mette Lampcov; Roger Hall / Scientific Illustration/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/87/09/8709e96f-4858-4418-83cf-3ce59481d36a/animal3.jpg)

Jewell’s enthusiasm for prints has not always won her favor. After she published her first rhino paper, some biologists chafed at its implicit critique of the traditional “dart-and-collar” approach. Others, she recalled, deemed tracking an antiquated form of “witchcraft.” In fact, she said, the reverse is true: The sophistication and flexibility of Zimbabwean trackers make Western scientific techniques look primitive. Take motion-activated camera traps, which, for all their virtues, only collect data where you put them. By contrast, Jewell pointed out, “footprints cover the landscape; you can pick them up anywhere. Once you’ve learned to look down, the earth is almost like a canvas buzzing with information.”

And that canvas doesn’t merely offer a portrait of other species’ lives. It demonstrates all we share with them. Throughout my evaluation in California, Reynerson and McFarland took pains to point out how conjoined evolutionary history manifested in tracks. The slender fingers of a raccoon recalled our own dexterous hands; mule deer prints occasioned a soliloquy on the anatomy of the hoof, whose keratinous sheaths are effectively the modified nails of our middle two fingers. “When we start to think of these animals as our cousins,” Reynerson said, “we suddenly understand tracks in a different way.”

A student tracker in California during a certification evaluation. Mette Lampcov/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/14/01/14013aa0-4497-4b84-9226-6ff38da7434d/nov2024_b14_animaltracking.jpg)

If tracking demonstrates our commonalities with wild animals, it also illustrates how thoroughly we’re annihilating them. At one point during the two-day evaluation, Reynerson and McFarland asked us to identify a male long-tailed weasel, his sharp face furred in a handsome black mask, that had been killed by a car. The weasel seemed to symbolize the horrors that humans wreak upon nature—and to suggest the tragedy inherent to modern tracking. To track in the Anthropocene is to document loss; as biodiversity collapses, its absence is reflected in the ground itself.

Yet tracking also indicates how much life remains. The evaluation’s final day was held at a park blanketed in oak savanna, a rich biome that teemed with sign. We identified the gooey feces of a turkey, the silken trap of a funnel-web spider, the stride of a roadrunner—a “cool little dinosaur of a bird that moves around in these arid lands,” Reynerson said. I pictured the roadrunner sprinting after a lizard, elongated feet stamping backward Ks upon the sand, and felt glad.

A student examines scat during an evaluation. Mette Lampcov/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/3f/a7/3fa75ea4-2095-4c12-bb55-90b129ae193e/nov2024_b20_animaltracking.jpg)

Perhaps this explains some of the growing fascination with tracking—the compulsion to reconnect to the wildlife we’re losing. As tracking’s ranks have swelled, its demographics have evolved. Among the evaluation assistants was Todd Cooley, a Black tracker from the Bay Area who works for an equity-

minded credit union. Many minority trackers confront an obstacle course of barriers, Cooley pointed out, including the cost of attending an evaluation (mine ran $360) and the safety and transportation challenges that come with getting out into nature. Hence Tracker Certification’s access committee, which has raised $25,000 to reduce barriers for participants, particularly those from historically marginalized groups. The group has held workshops at parks in Atlanta and Baltimore for Black and Indigenous trackers and other trackers of color, including biologists, open-space advocates and educators. Even in these citified spaces, Cooley said, the biodiversity “blew my mind.” Foxes deposited their fur-filled scats; mink left dainty prints in mud; beavers hewed streamside trees. Tracking brought urbanites into contact with hidden nature, and suggested new avenues for outdoor education and the preservation of green space. “I see it as this powerful piece to connect Black and brown people with each other and the natural world, and get healthier in their bodies and spirits,” Cooley said.

Later, I spoke with Vanessa Castle, a fisheries and wildlife technician with the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe, who, after beginning to track in 2021, realized it was a means of reclaiming her people’s traditional knowledge—“a reconnection with the way that my ancestors used to see the world.” She’s since mentored dozens of young tribal members, several of whom have passed their own evaluations, a potential pathway to jobs in fields such as natural resource management. “I have an obligation to the future generations of my tribe to continue teaching them those skills that I’m learning along the way,” Castle said.

In the end, I narrowly failed my own evaluation (though at least I’d been right about the bobcat). For days afterward, I was plagued by what Reynerson called the “haunting miss”: the dog prints I’d called coyote, the indistinct raccoon tracks I’d confused for fox. Yet my haplessness was beside the point. I now knew that a mourning dove’s scat resembled a cheese Danish, that male tarantulas carried their sperm packets in their leg-like pedipalps, that rabbits ate and redigested their own pellets. Who could put a price on such knowledge?

At the test’s end, our group gathered under an oak tree to debrief. McFarland reminded us of something that had been easy to forget, stooped in the dirt as we’d been: Every track, every scat, every chew mark was the “physical extension of an animal,” a flesh-and-blood creature. The mole tunnel had contained an actual mole, gorging on millipedes beneath our feet; the striped skunk tracks had been left by an actual skunk, loping down a dirt road to fulfill its secret ends. So many beings scurrying over the land—feeding, mating, killing, living—enduring everything we humans throw at them, thriving in spite of us, leaving their mark upon the world.