The big picture: It’s a scenario we’re all too familiar with – you head outside without an umbrella only for the rain to start pouring down. Instinctively, most of us hunch over and start hurrying, believing that getting to shelter faster will reduce how drenched we become. But is that instinct actually correct? A physicist has now broken it all down.

Jacques Treiner, a theoretical physicist at Université Paris Cité, has examined the effects of walking speed on the amount of rainwater a person encounters. His insights might just change your tactics.

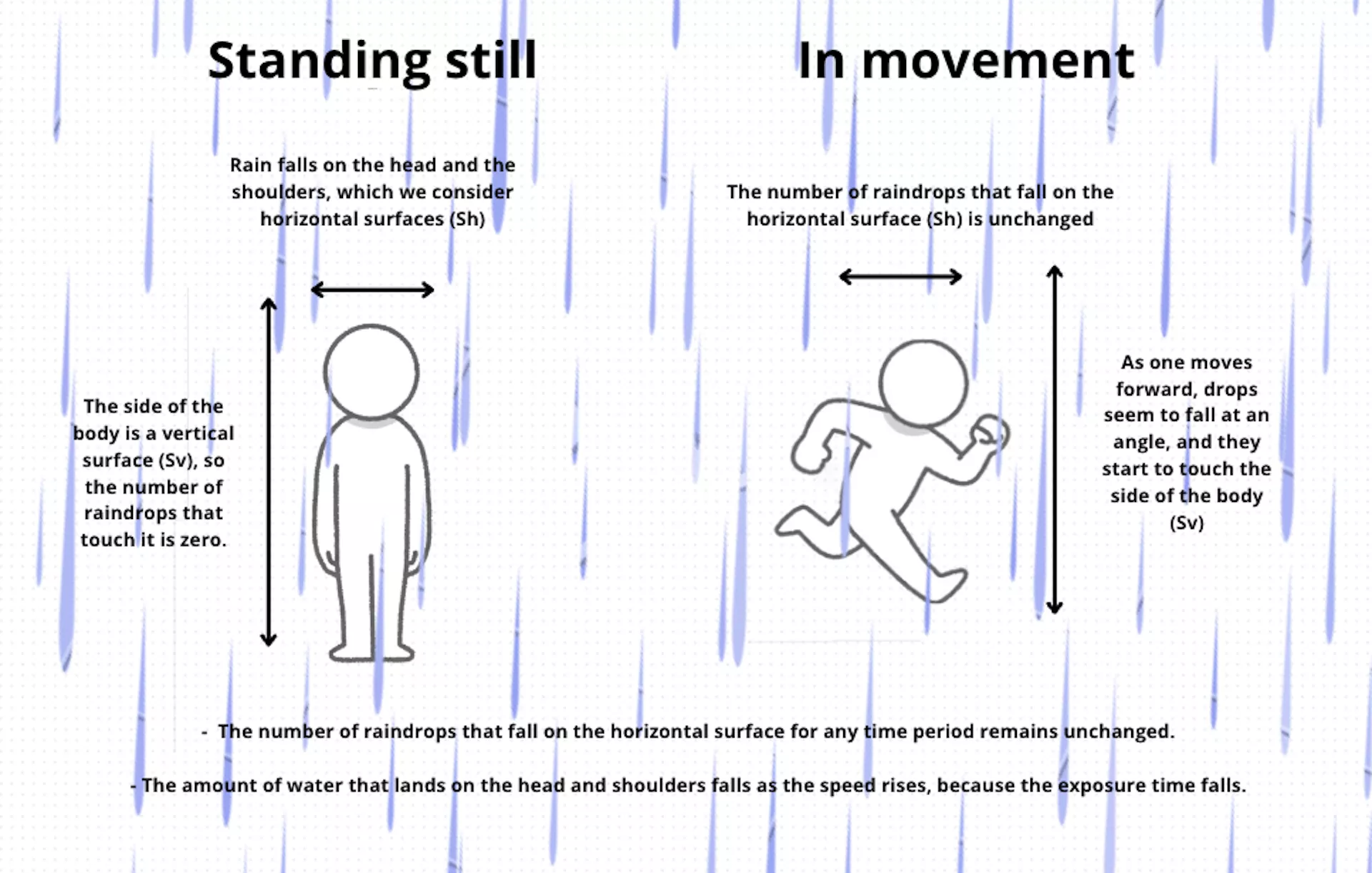

Treiner starts by dividing the human body into two surface areas – the vertical areas like your front and back, and the horizontal areas like your head and shoulders. When stationary in the rain, only the horizontal surfaces get wet from the drops falling directly overhead.

However, as soon as you start moving forward, things change. From your perspective, the rain appears to be falling at an angle due to your forward motion. That angled trajectory means raindrops that would have landed ahead of you now strike your front surface instead.

The faster you walk, the more angled and horizontal that rain trajectory becomes, increasing the number of drops pelting your vertical surfaces with each stride. While it may seem like a good case for taking it slow, things are not so simple.

While more drops may be hitting you from the front, the key is that you’re exposed to the rain for less time by getting to shelter more quickly. These two effects balance out – more drops per second at higher speeds, but less time in the rain overall.

For the horizontal surfaces like your head and shoulders, it’s a different story. Treiner’s calculations show that regardless of walking speed, the total number of drops hitting these areas is unchanged. You’re still getting rained on from above at the same rate.

However, by moving faster and reducing your time in the exposed rain, you ultimately encounter less total water raining down on the horizontal areas.

To conclude, according to Treiner’s mathematical model, the amount of water hitting your vertical surfaces is constant no matter your walking pace. However, the water drenching your head and shoulders decreases as your speed increases.

Of course, there are other factors at play too such as wind that may cause the rain to fall at an angle, drenching you even if you are standing still. Or the fact that if you’re caught in the rain for long enough, the water will eventually start dripping off the horizontal areas and drench you all over – regardless of your walking speed. But accounting for these would likely overcomplicate the formula.

So, for light rain without a lot of wind, the physicist’s verdict is that “It’s a good idea to lean forward and move quickly when you’re caught in the rain.” Just don’t hunch over too far or that increased head surface area could negate the speed benefits.

If you’d like to get to the bottom of the mathematics, you can access Treiner’s complete analysis over on The Conversation.

Masthead credit: Mette Køstner