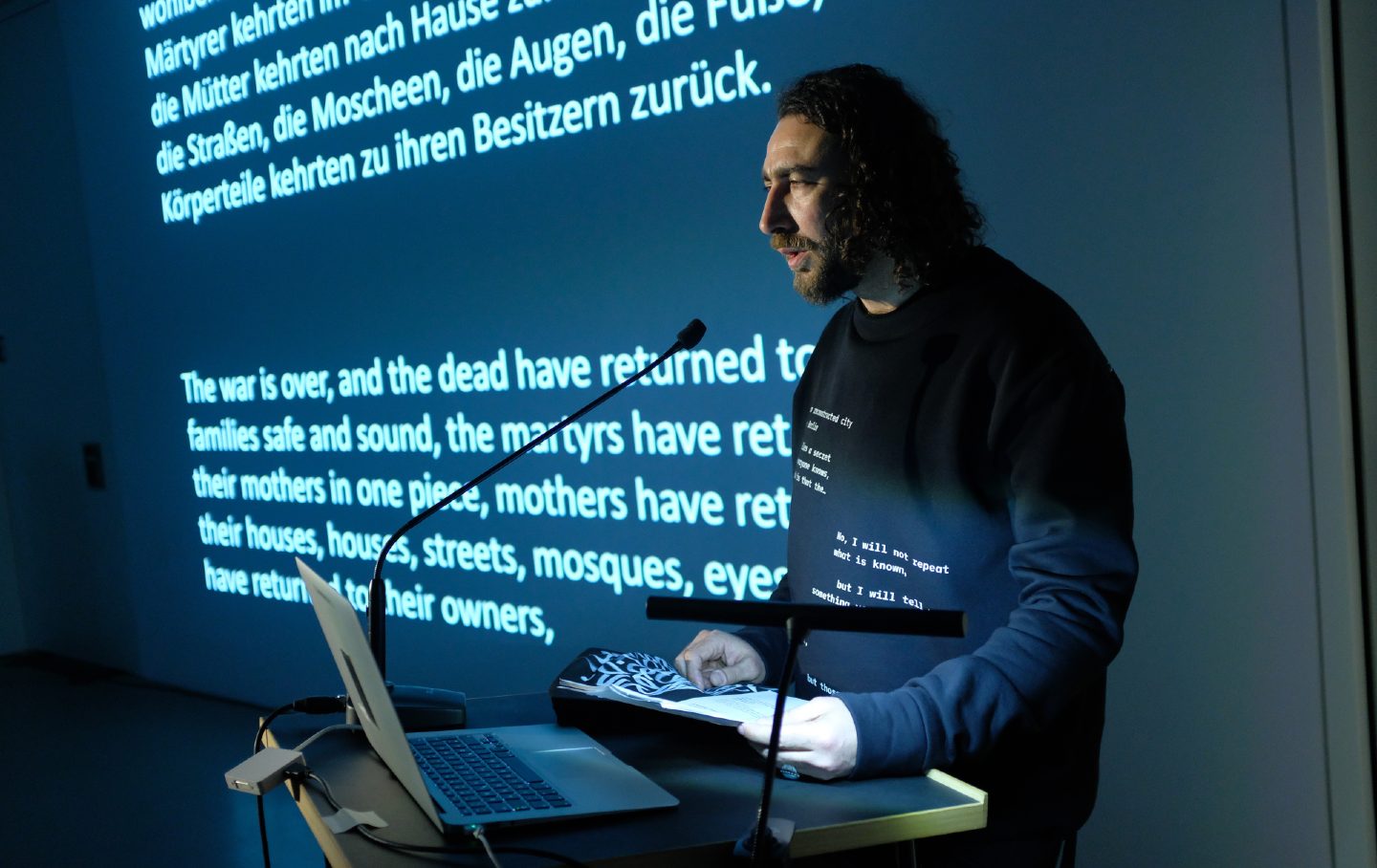

The poet Ghayath Almadhoun reads from “N-O-T M-Y P-O-E-M-S” at the DAAD Gallery on February 19, 2020, in Berlin, Germany.

(Sean Gallup / Getty Images)

Ghayath Almadhoun had a poetry event in Berlin canceled simply because he’s Palestinian. At least 200 more artists have been silenced over Palestine in Germany since.

My father, Rassem Almadhoun, is older than Israel. In 1948, he was 6 months old when Israel expelled my family from our home in Ashkelon. The city was the only part of Gaza Strip that Israel occupied during the Nakba.

My grandparents fled with their children and the keys to their house and settled in what is now the Khan Yunis refugee camp in Gaza.

My grandfather died there at 33, leaving my grandmother, Latifa, to raise their children in a tent that gradually became a house of zinc sheets and brick.

In 1967, when my father turned 18, Israel occupied the Gaza Strip, the West Bank, East Jerusalem, Sinai (from Egypt), and the Golan Heights (from Syria). Israel grew tenfold, from 20,000 to 200,000 square kilometers.

Around that time, the Israeli army arrested my father and other young men, took them on a four-day journey through the Sinai Desert without food, and abandoned them on the Egyptian side of the Suez Canal. My father eventually traveled to Jordan and then to Syria, where he met my Syrian mother. I was born in the Yarmouk Palestinian refugee camp in Damascus.

The Israeli army took my father from his mother and deported him to Egypt. My father had no choice but to leave his mother, and they were separated for the rest of their lives.

I tried everything to get Swedish citizenship so that I could visit my grandmother in Palestine. But it seems everyone can go to Palestine except Palestinians. Unfortunately, Latifa died in 2012 before I could get a Swedish passport.

When I was in Syria, my family and I couldn’t talk to her. The Syrian government bars calls to Israel, and because of the occupation, the Gaza Strip has the same international phone code as Israel and is therefore blocked by Syria.

After several attempts, I fled Syria in early September 2008 and arrived in Sweden. In Stockholm, I searched for a way to call my grandmother and discovered her home phone number.

I talked to her almost every day. She could hardly hear because of her age, but she was a great storyteller with a brilliant memory. She told me hundreds of stories about countless cousins of mine that I had never met and knew nothing about. She told me about at least a hundred cousins named Mohammed Almadhoun, Ahmed Almadhoun, and, of course, Ali Almadhoun.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

Then I had an idea. I bought another cell phone, called my grandmother in Gaza on one and my father in Syria on the other, and put them both on speakerphone so they could talk to each other after all these years.

Less than three months after I arrived in Sweden, Israel launched a war on Gaza in late 2008, bombing phone towers and cutting off communications.

When I finally heard her voice after the war, it was full of pride, as if she had just emerged from a victorious battle or were speaking live on Al Jazeera. Her words rang out with unwavering clarity: “We are here. We are steadfast. We will continue to resist. The Jews cannot break us.”

“Oh, you mean Israelis, not Jews,” I said.

“What do you mean?” she replied.

“I think you mean the Israelis can’t break us, not the Jews.”

“What’s the difference?” she asked.

There was a pause. I thought to myself, “Why should a woman born in Palestine in the 1920 be expected to parse the difference between Jews and Israelis, when the state of Israel itself obscures that difference? Why should she know about antisemitism in Europe? Why should a woman born a century ago, without access to today’s education, know European history when European intellectuals know so little about the Middle East beyond clichés and stereotypes?”

“Forget it, there’s nothing wrong with what you said,” I replied.

My grandmother died in 2012. I never saw her, and she never saw the Khan Younis camp, along with all of Gaza, wiped off the map.

Rassem Almadhoun—my father, a well-known writer and journalist—ended up in Syria, where he met my Syrian mother, Najieh Abo Nabout, a beautiful primary-school teacher from the city of Daraa. They married in 1978, and I was born on July 19, 1979, in the Yarmouk Palestinian refugee camp in Damascus.

I, of course, don’t want to give the Israeli occupation credit for anything, but without it, I wouldn’t be here now; my father never would have gone to Syria and met my mother. The thing you hate the most can be the reason for your existence.

My poem “Israel,” written in 2010, reads:

Israel

Without Israel, my father would not have been expelled from Palestine

Would not have fled to Syria

He would not have met my mother

I would not exist

You would not be my lover.

As I grew older, my search for answers about who I was and where I came from taught me the value of questions, especially the unanswerable ones. It taught me the essential role of instability and having an outsider’s perspective to making art and literature. Being without a homeland makes you an exile, an immigrant, a stateless vagabond, a displaced nomad, and a refugee—it’s a kind of privilege for a writer these days; it frees you from all the compromises that many writers make to maintain their position. You have nothing to lose if you’ve lost your country.

The only reason I don’t hate my country is because I don’t have a country, as I write in a poem.

Born in Damascus, I inherited my father’s exile. Later, I escaped the Syrian dictatorship and fled to Sweden, my own exile.

When the Syrian revolution began in 2011, I was all for it. But physically I was far away, facing for the first time the fact that I was neither here nor there.

I am the Palestinian-Syrian-Swedish refugee, wearing Levi’s jeans invented by a Jewish immigrant from Germany in San Francisco, filling my camera with pictures like a Russian peasant woman filling a bucket with milk from under her cow, nodding my head like someone absorbing a lesson, the lesson of war, I wrote in my poem “Schizophrenia” in 2015.

Read the poetry of Ghayath Almadhoun:

The destruction of Syria is so painful, because all that remains of my home is my memory. Just as my father’s memory is the only proof for him that Palestine is real, my memory has become the only proof that Damascus was ever real.

The destruction of Damascus shook everything in me. When Damascus was there, I assumed that one day, when I was exhausted from wandering, I would return. But when Damascus disappeared, the security I leaned on disappeared, and the stability I used to feel leaked out like water between my fingers.

I am a Syrian-born Palestinian. I have lost two countries.

My writing became a diary to help me survive, a therapy to me heal, and a way to translate my new reality into poetry. I am no longer Middle Eastern, and I will never be 100 percent Western. I am exiled from exile.

In Palestine, they call me the Syrian Swedish poet.

In Syria, they call me the Palestinian Swedish poet.

In Sweden, they call me the Palestinian Syrian poet.

When I fled Syria, I exchanged dictatorship for exile. Although exile is bitter, it brings the sweetness of freedom. It, however, also comes with unforeseen dangers. I’m an Arab, a Muslim, a Palestinian, an immigrant, a refugee, and a poet, and this makes me a target of the far right.

Being unwelcome, mixed with my outsider’s perspective, forced me to rethink everything—even what it means to be a poet. I was able to distance myself from my settled self.

I abandoned the poetic tools I had practiced in Damascus and found ones suited to my new home, where I no longer feared the ruling regime. I didn’t need to hide behind symbols and metaphors to avoid censorship and punishment, and I could rely less on metonymy and other tools that had once protected me. This shift was more than linguistic; it was about uncovering my hidden voice as a poet, and I began to touch what I now believe to be the essence of poetry.

The essence of poetry, I believe, is the voice of wandering souls, the testimony of witnesses denied the right to testify. It is through the eyes of an outsider that a poet can see the world with clarity. To be out of place is an imperative for poets to fully embrace their roles.

I wanted my words to be both direct and indirect, to pretend not to care and then suddenly touch the wound, to whisper intimately in a woman’s ear and to speak truth to power, to entertain and to criticize.

But criticism is not expected from the foreigner; exile came with a lot of bad love with good intentions in the name of tolerance. I’m against tolerance. It implies a hierarchy—one person or group is placed above another and decides to tolerate them from a position of superiority. No one should tolerate another. People must be equal.

Tolerance also implies gratitude; it demands that you be grateful, and I don’t want to be grateful to anyone or anything. Gratitude also distances you from criticism, and I believe that the right to criticize is one of the most important ways to measure freedom of expression in art. It’s important to remember who has been forbidden to criticize throughout history: natives against colonizers, slaves against masters, women against patriarchy, Jews against Nazis, and Palestinians against Israeli occupation.

The moment an immigrant criticizes something, the white man says, “Go back to your homeland.”

Exactly, that is my dream, to go back to my homeland: Palestine.

In 2015, I wrote in my poem “Schizophrenia”:

I’m thinking of Palestine, the country that invented God and caused the slaughter of millions in the name of God, the land of milk and honey where there is no milk and no honey. I’m thinking of Palestine and am haunted by the voice of the shaykh who repeated a line from the Quran whenever I questioned him: ‘Oh you who believe, don’t ask about things that, if they are made clear to you, will cause you trouble.’ I continued to ask myself: which is further from the earth, Jupiter or the two-state solution? Which is closer to my heart, a soldier from my country or a poet from my enemy’s country? What’s the worst thing Alfred Nobel did? Dynamite or the Nobel Prize.

Being physically removed from the place I knew allowed me to see my poetic potential differently. Writing took on a more existential significance—something I hadn’t realized while in Damascus, where every word was measured for fear of the infamous punishment Syria is known for: disappearance.

During the 30 years I lived in Syria, I had developed strategies to fight totalitarianism as well as how to survive and stay sane.

Freedom of expression is essential to me as a writer. That is why I fled Syria in 2008. I do not take democracy in the West for granted, and I believe that allowing differences of opinion maintains a healthy democracy, and that art in a free environment is the greatest enemy of totalitarianism.

As we all know, words have no consequences here in the West, or at least that’s I thought at first. I was wrong.

I never expected to find myself fighting totalitarianism in democracies, but here I am in 2024, for the second time in my life, fighting censorship, but this time in Germany. My efforts didn’t work, mainly because the tools that I had developed were not designed to fight totalitarianism in democracies.

Germany has learned so little from its history. It is brutally suppressing democratic values. We are witnessing a period of systematic suppression and cultural cancellation on a massive scale in a country known for its dark past. Everything from poetry readings and book launches to award ceremonies and music events have been banned. Exhibitions, film screenings, lectures, and literary seminars have been closed. Academics have been forced to resign, and cultural centers have been shut down. It is one of the largest cancellations in contemporary European history to take place in a single year. The frightening thing is that the cancellations that happened in fascist Europe in the 1930s were predictable, because that’s what you expect from totalitarianism, but what’s happening now is occurring in a democracy.

What is even more frightening is that if you look at the list of cancellations in Germany, about 22 percent of the nearly 200 canceled artists are Jewish. Considering that Germany has about 83 million people of Christian background and at most 200,000 Jews, it’s fair to say Germany is canceling Jews.

And so here we are, watching the Germans, for the second time in their history—their governments and people, on the right and left, groups and individuals, public and private, independent and non-independent—engage in an organized, collective effort to censor, silence, and erase the voices of a group of people. They are denying them their rights, treating them as enemies, and dehumanizing them.

Because of Germany’s dark history, we Palestinians were forced to give up our homeland as compensation for the Holocaust perpetrated by Germany’s white supremacists. Now the Palestinian community in Germany—the largest in the world outside the Middle East—finds itself living in an unwelcoming society that labels our identity as dangerous, our quest for equality as politically incorrect, and our longing for freedom as a threat.

I was one of the first artists to be canceled in Germany.

The highly respected Haus für Poesie in Berlin, with whom I have been involved in many readings and projects for over a decade, had decided to cancel the launch event for the poetry anthology Kontinentaldrift: Das Arabische Europa, which I had curated and edited for them. I received an email on October 12, 2023, five days after the October 7 attacks, informing me of the cancellation. I should clarify that they sent me an email two days before the attacks confirming that everything was ready for the anthology presentation.

Now there are likely hundreds of canceled artists in Germany. Many of us are no longer involved in any artistic activities; we have lost most of our income and are unable to understand or deal with this phenomenon in a democracy.

The nearly 200 cases documented in the Archive of Silence—an online platform curated by a group of intellectuals and activists to document and publish the list of cancellations that have taken place in Germany since October 7—are just the public cases. Many artists choose not to go public with their cases for fear of being labeled antisemitic and losing their jobs and careers.

I consider my cancellation to be one of the most serious, and I’ll explain why, using the example of the cancellation of the award ceremony for a novel by the acclaimed Palestinian writer Adania Shibli at the Frankfurt Book Fair. Shibli’s book, Minor Detail, is a novel about Palestine based on a real event that occurred on August 12, 1949, and was exposed by the Israeli newspaper Haaretz in 2003. The novel tells the story of a Palestinian girl who was raped by 20 Israeli soldiers, then later executed and buried in the desert.

What makes my cancellation one of the most serious is that, unlike Shibli’s book and the work of other artists, the anthology I curated had nothing to do with Palestine. It included poems by 31 Arab poets living in Europe and is part of a series of anthologies by the Haus für Poesie, the previous ones being Black Europe and Persian Europe.

The anthology has no politics, no mention of the occupation, and no hate or antisemitism. There is nothing that links the book to Palestine or criticizes Israel, and I haven’t made any public statements.

The seriousness of my cancellation lies in the fact that I was cancelled because I am Palestinian, and only because of that, which is what Germany did in the 1930s, punishing people because of their identity.

Finally, we must remember that the freedom we enjoy in Western countries is not a given and should not be taken for granted. Rather, it has been hard-won through struggle, as is the case for most people around the world. It is therefore imperative that we continue to fight to preserve it. I want to end by reminding you that people often say: “We didn’t know what was going on in the 1930s.” Well, I have told you all this, because I want you to leave your zone of interest and bear witness to the times in which we live today. You know what’s happening. Now you must do something.

More from The Nation

In The Hidden Globe, Atossa Araxia Abrahamian examines what globalization has come to look like for the wealthy.

Mexico’s new president, Claudia Sheinbaum, has a plan to combat drug trafficking, but she has a problem: Donald Trump.

I survived eight terrible months of genocide. Now, I’m in exile—but I can’t stop thinking about the women who have remained.