July 9, 2024

The new president in Tehran is likely to renew outreach to the United States.

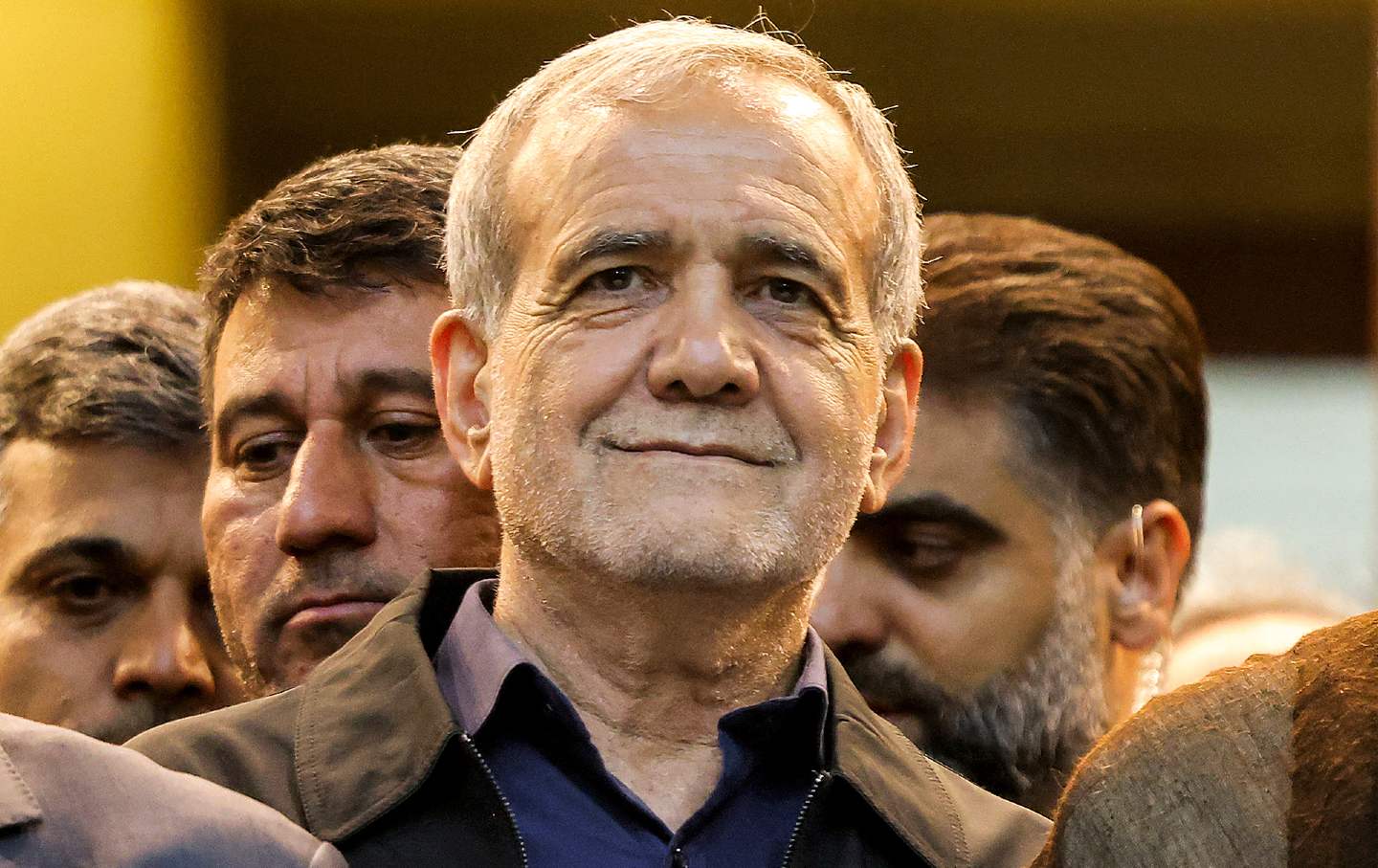

And just like that, Iran’s seemingly frozen politics has come unstuck. Less than two months after its hard-line president, Ebrahim Raisi, a religious conservative and former prosecutor who’d overseen mass executions of political prisoners, died in a helicopter crash in May, Iran’s president-elect—surprise!—is a reformist who’s pledged to pursue open diplomacy with the United States and to halt Tehran’s crackdown on women refusing to obey the country’s hijab laws.

The election of Masoud Pezeshkian, a former minister of health and a deputy speaker of parliament from Iran’s northwest, promises to bring the sidelined reformist movement back to the center of Iranian politics. That movement had its heyday during the presidency of Mohammad Khatami (1997–2005), but since then Khatami has essentially become a nonperson in Iran, with authorities refusing to allow Iranian media even to mention his name. And Mir Hossein Mousavi, the last reformist to run for president, has been under continuous house arrest since losing in 2009 to the radical-right President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, in an election that is widely considered to have been fraudulent.

Now, as president, Pezeshkian will be in position to steer Tehran away from the spiraling showdown with Washington that has been building since President Donald Trump blew up the US-Iran nuclear agreement in 2018. To be sure, he’ll face strong resistance to a change in direction from Iran’s deep state: Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, a parliament and a justice system dominated by hard-liners, and the all-powerful Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC). But he’ll have the support of Iran’s population, which has been crushed under an economy straitjacketed by US economic sanctions and which has been in a near-constant state of revolt for the past five years, including over the regime’s oppressive hijab laws and suppression of free speech.

On June 28 Pezeshkian placed first in a four-man field (including three conservatives) in the election’s first round. In the second round, on July 5, he faced Saeed Jalili, an ultra-hard-liner, winning 53.6 percent of the vote against Jalili’s 42.5 percent. While some observers expected voters to consolidate behind the conservative Jalili, who was clearly favored by Khamenei and by the IRGC, Pezeshkian managed to assemble a coalition of Iran’s urban, educated elite, young voters, and—as a half-Turkish, half-Kurdish politician from Tabriz—the country’s non-Persian minorities. Though turnout overall was still historically low when compared to previous presidential elections, it seems that enough pro-reformist voters managed to overcome the deep pessimism and cynicism that has become the hallmark of recent Iranian campaigns to turn out for Pezeshkian.

In televised debates with Jalili, Pezeshkian drew a straight line between Iran’s flailing economy and the isolation Iran has suffered since Trump’s unilateral withdrawal from the nuclear accord, known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), and the imposition of so-called “maximum pressure” sanctions that all but shut down Iran’s oil exports. And by all accounts he’s pledged to reassemble the team of advisers and diplomats who negotiated the JCPOA with President Obama and representatives of Russia, China, England, France, and Germany. Among those expected to be appointed to his administration later this summer is Javad Zarif, the English-speaking, American-educated former foreign minister who led Iran’s JCPOA team under President Hassan Rouhani (2013–21).

During the final debate before July 5, Jalili slammed Pezeshkian for his plan to bring back the JCPOA team. “Are the people around you not [former President] Rouhani’s ministers? Wasn’t Mr. Zarif Rouhani’s minister?” said Jalili. “Is Zarif, with his ineffective performance, part of your campaign team or not?” Jalili, of course, opposed the JCPOA from its inception, and earlier had been in charge of nuclear talks for Ahmadinejad that deliberately went nowhere.

Besides Zarif, who’s widely respected in the West for his understanding of global affairs, it might be equally important that Pezeshkian has received the support of Kamal Kharrazi, who served as foreign minister under Khatami. According to the Tehran Times, Kharrazi, who heads a think tank called the Strategic Council on Foreign Relations, is “ready to assist the government in solving problems arising from unjust Western sanctions against the Iranian people and securing the country’s interests with dignity and authority.” Significantly, back in 2003, Kharrazi, Zarif, and Kharrazi’s nephew Sadegh Kharrazi were intimately involved in offering an olive branch to the United States called the Grand Bargain. That proposal offered to resolve a wide range of differences between Tehran and Washington, from the nuclear issue to the Israel-Palestinian problem. But it was cavalierly ignored by the George W. Bush administration, and President Bush famously lumped Iran into what he called the “axis of evil.”

On both the international front and domestically, Pezeshkian faces a tough road. He undoubtedly remembers how hard-liners sabotaged Khatami’s presidency when he challenged some of the regime’s shibboleths. During the campaign, he repeatedly condemned the government’s brutal repression of women who refused to wear the hijab, though he admitted candidly that as president he’d be unable to change the law or get it repealed by a right-wing-controlled parliament. Yet he should be able to rein in the law’s enforcers, who drag women into vans for not complying. (I’ve witnessed that myself on the streets of Tehran.) In 2022 and ’23, most of Iran’s cities were wracked by demonstrations and protests over the hijab laws, leading to killings and mass arrests by the police and the IRGC. Many of the protesters expanded the protests to demand the toppling of Khamenei himself.

It’s hard to say who might have been more surprised by the results of Iran’s July 5 presidential election runoff: Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, or America’s neoconservatives and anti-Iran hard-liners.

For years, those hard-liners, who’ve called for regime change, for bombing Iran’s nuclear research sites, for imposing North Korea–style isolation on Iran, have argued that Iran is an absolutist dictatorship where elections don’t matter. (They’re less exercised over Saudi Arabia, an American ally that has no elections at all.)

This time around, the American neocons and their allies, who say that the supreme leader always gets his way, found their predictions falling flat. It will be a “rigged election…stage-managed by the ‘Supreme Leader,’” said Mark Dubowitz of the right-wing Foundation for the Defense of Democracies. Pezeshkian, said the folks at War on the Rocks, “does not have a constituency and therefore does not pose a challenge to the Supreme Leader’s preferred candidate.” Danielle Pletka, who long headed the American Enterprise Institute’s national security team, wrote, “Raisi will be replaced by someone just like him.”

And the experts at United Against Nuclear Iran, perhaps the leading American cheerleaders for war against Tehran, opined before the vote that it “is unlikely that Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei will allow [Pezeshkian] to win, making him a sacrificial lamb used to disguise the regime’s electoral engineering.”

In Washington, that circle is now counting on an escalation of the ongoing armed conflict in Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, and Yemen—where Iran has great influence through its support of anti-Israel and anti-American governments and paramilitary groups—to undermine whatever Pezeshkian can achieve in the diplomatic area. And if, as looks increasingly likely, Trump is reelected, President Pezeshkian can expect to find himself confronted with an existential threat.

Thank you for reading The Nation

We hope you enjoyed the story you just read, just one of the many incisive, deeply-reported articles we publish daily. Now more than ever, we need fearless journalism that shifts the needle on important issues, uncovers malfeasance and corruption, and uplifts voices and perspectives that often go unheard in mainstream media.

Throughout this critical election year and a time of media austerity and renewed campus activism and rising labor organizing, independent journalism that gets to the heart of the matter is more critical than ever before. Donate right now and help us hold the powerful accountable, shine a light on issues that would otherwise be swept under the rug, and build a more just and equitable future.

For nearly 160 years, The Nation has stood for truth, justice, and moral clarity. As a reader-supported publication, we are not beholden to the whims of advertisers or a corporate owner. But it does take financial resources to report on stories that may take weeks or months to properly investigate, thoroughly edit and fact-check articles, and get our stories into the hands of readers.

Donate today and stand with us for a better future. Thank you for being a supporter of independent journalism.

More from The Nation

The socialist mayor of Paris has promised that the Olympics can make Paris greener, cleaner, and safer. With the left triumphant, will this actually happen?

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25746461/Timestop_D_20_DnD_watch.jpg?w=420&resize=420,280&ssl=1)