Even among Mexican cartel bosses — a bunch known for lavish wealth, daring escapes and extreme brutality — Ismael “El Mayo” Zambada stood out.

He was a longtime partner of Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán, and together they built the Sinaloa cartel into a global empire. Taking on an almost mythic status, he is rumored to have judges, generals and even presidents of Mexico in his pocket.

And despite more than four decades on the run as one of the world’s most wanted fugitives, he had never spent a single night in jail.

Until Thursday.

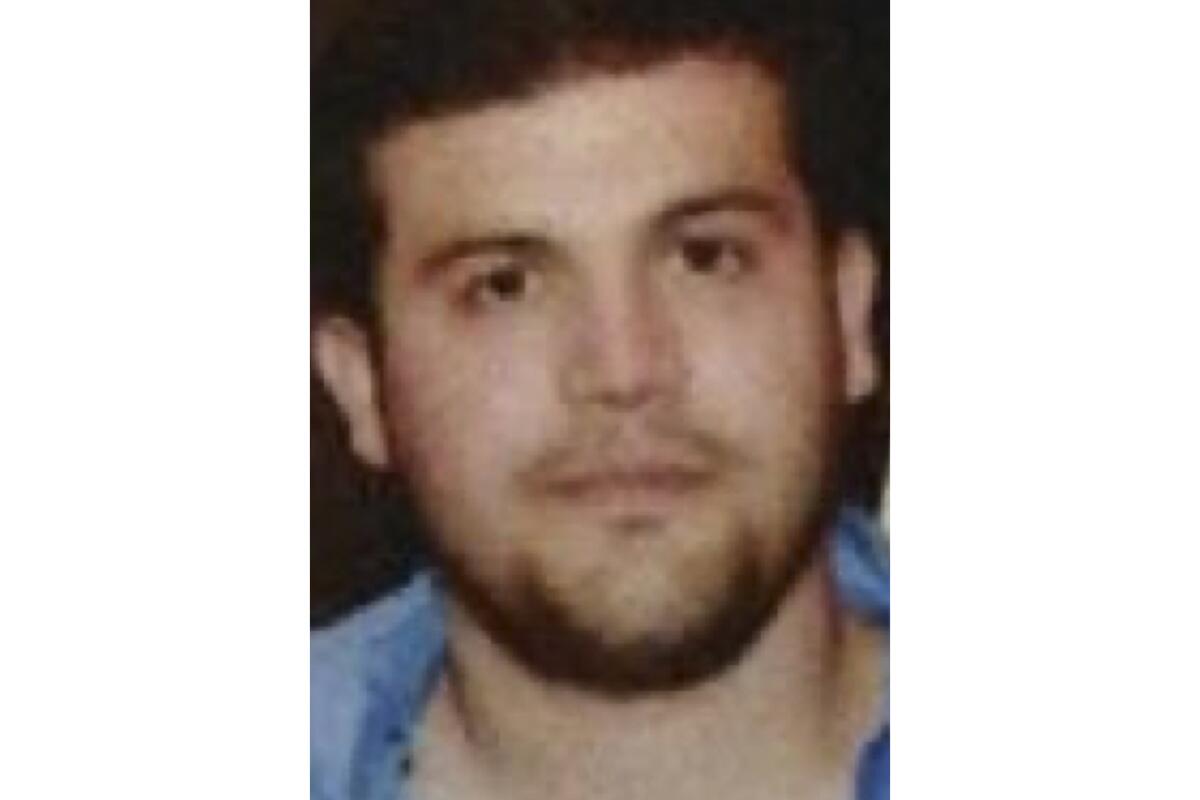

Zambada, 76, was arrested at a private airport near El Paso, along with El Chapo’s son Joaquín Guzmán López, the Department of Justice announced. On Friday morning Zambada pleaded not guilty to an array of drug, weapons, money laundering and conspiracy charges, including trafficking the powerful synthetic opioid fentanyl that has fueled a U.S. epidemic of overdose deaths.

Ismael “El Mayo” Zambada was detained at an airport near El Paso on Thursday.

(DEA)

A judge ordered Zambada detained with no bond and set a Wednesday court date to determine next steps.

The stunning turn of events has sparked fear and uncertainty in Sinaloa, the Pacific coast state where Zambada had been credited with brokering a fragile peace between rival cartel factions. And it has generated a torrent of rumors and speculation about how exactly U.S. authorities managed to capture a man who traveled with a heavy security detail and so routinely outfoxed his pursuers that some people called him “ghost.”

Zambada’s lawyer, Frank Perez, denied reports that his client had turned himself in.

“I have no comment except to state that he did not surrender voluntarily,” he said. “He was brought against his will.”

According to sources familiar with the situation who were not authorized to speak publicly about the arrests, Zambada was duped into boarding the plane that brought him to U.S. soil.

“Epic, once-in-a-lifetime caper,” said one law enforcement source who works in Mexico. “The old man got tricked.”

If Guzmán López played a role in the operation, U.S. officials have not discussed it publicly. The 38-year-old leader of the Sinaloa cartel faction known as Los Chapitos is facing a federal indictment on drug, money laundering and firearms charges.

Rosa Icela Rodríguez, Mexico’s security secretary, said the Mexican government did not participate in the operation, and didn’t know the details of the arrests.

“You ask if it was a delivery, if it was capture,” she told reporters. “That is part of the investigation and part of the information that we would be expecting from the government of the United States.”

Mexican authorities said they were notified around 2:30 p.m. Thursday that the two men were in custody. U.S. authorities subsequently sent photos of the pair, which were released with partial redactions in a Mexican government report Friday.

Joaquín Guzmán López, son of Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán, in an undated photo.

( U.S. State Department via AP)

Zambada’s hair was still dark, but he appeared gaunt and scowled at the camera. Joaquín Guzmán Lopez appeared heavyset, with thick stubble on his jowls.

Mexico’s report said the small jet carrying Zambada and Guzmán López had departed from the city of Hermosillo around 8 a.m. local time Thursday and landed about 2½ hours later.

U.S. law enforcement officials celebrated the arrests, which President Biden said would help “save American lives.”

Experts on the drug trade, however, said the detentions are unlikely to affect the day-to-day business operations of the Sinaloa cartel — and could end up sparking a bloody conflict as members battle to fill a new power vacuum.

The capture of Zambada spelled a likely end to the long and storied career of a drug kingpin whose trajectory has been closely intertwined with the rise of narcotrafficking in Mexico.

In the Netflix docudrama series “Narcos: Mexico,” which depicted his rise to power, he was portrayed as handsome, rakish and a cool customer — traits those who have known him say are accurate. His origin story begins in the late 1980s, when Miguel Angel Felix Gallardo, then Mexico’s most important cocaine trafficker, sat down with several of his proteges — including Zambada — to divide control of different drug routes.

Miguel Angel Felix Gallardo is shown in 1989.

(Associated Press)

But a few years later, a battle for territory broke out between Felix Gallardo and Zambada, who forged a partnership with El Chapo and an ex-cop-turned-trafficker named Juan José Esparragoza Moreno. The Sinaloa cartel was born.

As appetites for drugs exploded worldwide, so did the business of his Sinaloa cartel, which authorities say is active on six continents and reaps billions of dollars in profits annually.

When Bloomberg named Zambada to its Billionaires Index in 2018, it put his net worth at $3 billion.

While other kingpins flaunted their wealth, Zambada lived a comparably modest life tucked away in the safety of the sierra, where he generated goodwill among locals by building roads and churches.

He gave just one interview, in 2010, to the famed journalist Julio Scherer García.

In the subsequent article, published in Proceso magazine, Scherer described a dizzying series of car rides and stays at safe houses before he was finally taken to meet Zambada in a rustic building where they sat down together to eat lunch.

The journalist wrote that Zambada was built “like a fortress” and wore blue jeans and a T-shirt. He lived with his wife, five girlfriends and a collection of children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

Zambada said he wasn’t interested in fame or luxuries. “The mountain is my home, my family, my protection,” he said.

Over the years, many of the traffickers who Zambada had started out with began to fall — killed by rivals or ensnared by law enforcement. But Zambada himself seemed untouchable.

Several members of Zambada’s family have already faced justice in the United States, including his brother and three of his sons. The other Zambadas all pleaded guilty to federal drug charges and have seen their cases resolved, sometimes with relatively short prison sentences.

Police officers and journalists stand near a haul of 1.8 tons of methamphetamine in Madrid on May 16. Spanish police said they dismantled a major methamphetamine distribution network of the Sinaloa cartel in the bust.

(Manu Fernandez / Associated Press)

Brother Jesús “El Rey” Zambada, who testified as a cooperating witness against El Chapo, pleaded guilty to drug trafficking in 2019 and has since been released, appearing publicly to promote his attempts to launch a music career.

Ismael Zambada’s son Vicente Zambada Niebla, 49, also testified against El Chapo, describing the fierce loyalty between the kingpin and his father. He said the two men long pooled their resources to fund drug shipments, battle rival cartels and bribe Mexican officials.

The cooperation of El Mayo’s relatives against El Chapo led to tensions in the Sinaloa cartel. The arrest of El Chapo’s son Ovidio Guzmán in late 2019 led to cartel gunmen flooding the city and holding civilians hostage, a spasm of violence on the minds of many locals after this week’s arrests.

Miguel Angel Vega, a journalist who covers organized crime for the Sinaloa newspaper RioDoce, said the mood in Culiacán, Sinaloa’s state capital, is tense.

“War is about to break out,” Vega said. “It looks like things are going to get ugly again. This time it’s going to be worse. Last time, it was within the same factions. Now we’re talking about two different factions.”

In its 2024 “Threat Assessment,” the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration described the Sinaloa cartel as “one of the most violent and prolific polydrug-trafficking cartels in the world,” responsible for the smuggling of fentanyl and other drugs into the U.S.

The report said daily deliveries range “from smaller packages carried by human ‘mules’ to thousands of pounds commingled with legitimate trade goods carried by tractor-trailers.”

The cartel has several factions. El Mayo’s and Los Chapitos are reputed to be the most powerful, with thousands of heavily armed sicarios, or assassins, controlling territory that stretches the length of Mexico.

DEA Administrator Anne Milgram talks during a news conference in Los Angeles on June 18, when the Justice Department announced a 10-count superseding indictment charging Los Angeles-based associates of the Sinaloa cartel.

(Jamie Ding / Associated Press)

The group’s stronghold is in Sinaloa, where El Mayo has long been said to freely roam Culiacán and the surrounding mountains. He has a reputation as a peacemaker who has sought to end wars and avoid violence that attracts attention from the government and is bad for business.

As for the flow of illicit drugs to the United States now that the Sinaloa cartel has lost two leaders, experts said little would change.

Cecilia Farfán-Méndez, a researcher at the Institute on Global Conflict and Cooperation, said that while Zambada was “a mythical figure,” the Sinaloa cartel has a deep bench of eager workers who would ensure that their product continues to be trafficked north.

“There are a lot of middlemen and middlewomen,” she said. “It’s an organization that is extremely resilient to these kinds of disruptions.”

That’s what happened in the past, when El Chapo was arrested. Violence broke out in Sinaloa state and elsewhere and a faction aligned with Zambada battled another one backing the Chapitos.

“But day to day, the drug market didn’t change,” she said.

Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman, head of the Sinaloa cartel, is escorted to a helicopter in Mexico City following his capture in the beach resort town of Mazatlan in February 2014.

(Eduardo Verdugo / Associated Press)

She also questioned how much of a leadership role Zambada had in recent years. The DEA said he was sick with diabetes, and Farfán-Méndez believes he had stepped back.

“To say he was in control of everything is incorrect,” she said.

One of his sons, Ismael Zambada-Sicairos, born in 1982 and known as “Mayito Flaco,” is a fugitive in Mexico, wanted by the DEA for his alleged leadership role in his father’s operation.

Eduardo Guerrero, a security expert with Mexico’s Lantia consultant group, said Zambada had largely retired from the business.

“Zambada knew that he would be arrested soon, and besides that he was very sick,” said Guerrero. “For a few months now he hasn’t been involved in the operations of Sinaloa.”

In his 2010 interview, Zambada was eloquent and incisive, speculating about what would happen if he was one day killed or captured.

“After a few days, we’d see that nothing had changed,” he said. “The drug problem involves millions. If the bosses are locked up or killed, their replacements are already waiting.”

Hamilton reported from San Francisco and Linthicum from Mexico City. Times staff writer Patrick McDonnell in Mexico City contributed to this report.